The Week That Could Have Changed Irish History, But Didn't.

Rushed legislation fails the very victims it was intended to protect. A look at the Mother and Baby Homes Records Bill and where it all went wrong. Article updated 30.10.20 in recognition of both Presidential and Government statements.

In a tumultuous week in Irish politics, Hozier, among others, criticised the Irish Government on Twitter in the days following the controversial vote which inadvertently ‘seals’ the archives detailing the abuse suffered by Women and Children “tantamount to human trafficking” at the hands of the Catholic Church and The State. The Bill which brought an end to the Commission Investigation has left a nation with whiplash, and as we try to pick up the pieces of what happened - it is probably easiest to start at the beginning.

What were the Mother and Baby Homes?

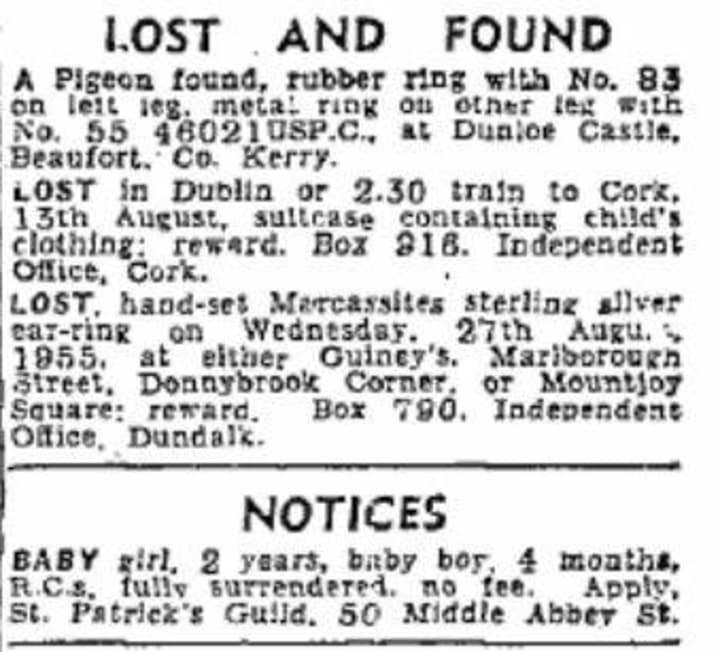

The Mother and Baby Homes were Church-run institutions for unmarried girls and women to deliver their children. The institutions were renowned for their systematic abuse, unpaid and forced labour, forced adoptions and sales of babies and children. It is believed that 35,000 girls and women, majority under the age of 23 years old entered these institutions, where they weren’t afforded medical care, were forced to carry out unpaid work, were denied communication from their friends and family and denied clarity on when they would be freed. The women were subjected to sexual abuse and were sterilised unwillingly. It is believed that 6,000 babies and children died in the years that the Homes were in operation. They died of neglect, malnutrition, abuse and failed medical trials, and more often than not were not provided with public burials and their mothers were not notified. The surviving children were adopted out without the consent of their mothers, and from the 1950s onwards were sold. In some cases, children were advertised in the St. Patrick’s Guild for adoption under the ‘lost and found’ notices.

The Mother and Baby Homes, followed by the Magdalene Laundries, operated from 1904 to as recently as 1996 without State intervention. The closure of the last home came in a tidal change in Ireland as the abuses of the Church became more and more clear and power was lost. The 2009 book and 2013 film Philomena provide an extra-ordinary insight into the Mother and Baby Homes, from a first hand account of a survivor.

The State and The Mother and Baby Homes

The McAleese Report published in 2013 established the States involvement in the Magdalene Laundries, and pinned some blame on the Garda Síochána also (the national police force). The landmark report revealed that 2,500 women were incarcerated directly by the State into the Laundries; a figure that one can assume to be higher but many records had been destroyed before the investigation. It was found that the State created lucrative deals between the Laundries and various hotel chains and army barracks to clean their bed linen, but without complying with the Fair Wages Clause and Social Insurance obligations. The State also inspected these Laundries under the Factories Act, and in doing so, oversaw systems of forced and unpaid labour. It was verified that women were held there without clear cause, without a release date and without contact from their friends and family. Gardaí were identified for playing a role in keeping these women incarcerated in the Laundries, returning escapees and acting on ad hoc. The State apologised for their involvement but lobby groups were left unsatisfied with the lack of meaningful action.

It wasn’t until the discovery of nearly 800 remains of babies in a septic tank in Tuam, Co. Galway that further was action taken. The bodies, originally discovered in 1975 were believed to have been from the Great Famine, and the burial site was resealed but in 2013 the truth was uncovered. A public servant working in Galway at the time retrieved death certificates of 796 babies and children, with ‘The Tuam [Mother and Baby] Home’ listed as their place of death. The death certificates were compared to public graves, and only two graves were found for the children listed, meaning that the remaining were buried secretly. Local maps identified the septic tank of the Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home as the burial site for the babies. There was no public record made of the burial, but elderly neighbours of the area remembered seeing the Nuns bury the infants. Nearly 800 bodies, meticulously arranged in order of size, wrapped in old papers and placed on purpose built shelves were discovered in the septic tank. The @BabiesTuam Twitter account shares the names and ages of the children that died in their memory and NUIG created a podcast telling the stories of the survivors of the Tuam Mother and Baby Home, you can find it here - https://www.nuigalway.ie/tuam-oral-history/.

In response to the discovery that broke the hearts of the nation, the Commission of Investigation Into Mother and Baby Homes and Certain Related Matters was established in 2015. The Commission set about finding and retrieving all available records from all of the Mother and Baby Homes. Fifteen homes supplied documentation, three homes said that they no longer had any documentation for whatever reasons, and four additional county-homes provided documents. The Commission now holds some 60,000 records, all of which are copies of the originals. The Commission also interviewed 500 survivors, both mothers and children, and collected the testimonials as part of the investigation. The testimonies were largely made in confidence, with some providing full details of their names, age at the time and other personal details. The Commission is the final report into the Mother and Baby Homes and investigated on eight grounds, ranging from grounds of entry, grounds for adoption, and grounds for mistreatment such as religion, race, ability, etc., among others. The investigation had a deadline of 2020.

Why is this surfacing now?

The self-imposed deadline of the Commission is the 30th of October 2020, and is fast approaching. Under the 2004 Act which allows Commission Investigations, their databases and archives are sealed for 30 years. The report is some 4,000 pages long and is a vital piece of Irish History but fears arose over data being lost in a transfer process due to legal obligations, or the archives being lost completely if they are dissolved on the 30th of October. O’Gorman, the Minister for Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth believed that a transfer to Tusla would be the safest way to protect these records, and so the Mother and Baby Homes Records Bill was created. However, transferring the records to Tusla has greatly disgruntled the survivors as they feel the State Child and Family Agency has already failed them and they simply do not trust it going forward.

“The Draft Bill is focused on protecting valuable resource which will assist in accessing personal information under existing law and be hugely beneficial in any future information and tracing legislation” - O’Gorman speaking on the Mother and Baby Homes Records Bill.

The Bill was very short and specific, but failed to address the 2004 Act which seals the records for 30 years. In the Dáil, 60 amendments which dealt with the issue of the seal and other concerns fronted by opposition politicians on behalf of the survivors, archivists and human rights experts, were rejected without debate. When it came to voting on the matter, the Minister imposed the Party Whip, meaning members of the Government parties lost their free vote and had to vote in alignment with the government. The Bill was passed by 78 votes to 67, putting access to the archives beyond the life expectancy of the survivors and therefore removing their ability to access their personal information, identity and right to ownership over their own trauma. Sealing or ‘preserving’ the archives, as the Government frames it, also puts access to the archives beyond the life expectancy of anybody who may have been held accountable by the investigation. The failure to publish the archive makes it impossible to begin any sort of legal proceedings to seek justice for the victims and survivors of the Homes. The Bill returned to the House of the Seanad where it was voted through despite concerns of the legality of it.

Watch: Holly Cairns TD pleads with Minister O'Gorman for justice for victims.

The Legality of The Law

On the evening of the Seanad vote, the Data Protection Commission found the Bill to be in breach of European and Irish Law in relation to people’s rights to access their personal data. The DPC also assured the public that this was communicated to the Department of Children before the Bill was drafted. Deputy Data Commissioner Graham Doyle cited the 2018 GDPR Act “explicitly amended” the 2004 Commission of Investigation Act which requires the records to be sealed. However, in a statement made in the hours following this assertion, O’Gorman disagreed with the DPC’s finding and stated that he believes that the 2004 Act outweighs the 2018 GDPR Act. The Bill has successfully passed through both houses of the Oireachtas to the final stage of Presidential signature. However, Article 26 of the Constitution allows for the President to consult the Supreme Court on the Bill before signing into law, and in regards to the legal discrepancies in the Bill there are clear grounds for this action.

Public Reaction

Emotions ran high as the result of the vote broke, with celebrities such as Hozier and Blindboy leading the way with public condemnations of the Government for their rushed handling of the Bill resulting in the archives being sealed. Hozier related the actions of the Mother and Baby Homes to human trafficking and Blindboy explained to his international audience that the Government did something ‘evil’ and ‘they did it most likely to protect evil people who can still be held accountable’. David Keenan called the government cowards, and accused the Government of rewriting history ‘once again to suit the few’. The public and survivors launched Twitter campaigns under the hashtags ‘RepublicofShame’, ‘Stand4Truth’, ‘RepealTheSeal’ and ‘UnsealTheArchives’ and human rights lawyers have outwardly condemned the Bill.

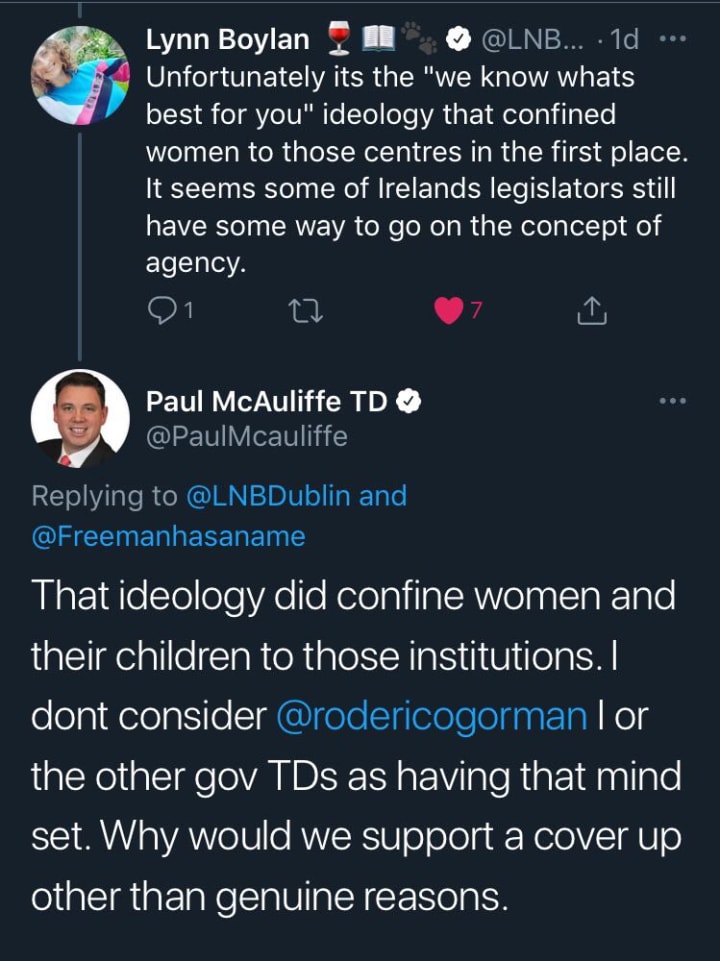

Tensions boiled over as politicians rushed to social media to defend their votes, taking narrow views on solely what the Bill entailed but not accepting what they inadvertently voted on in the process. Heated exchanges between the politicians followed and revealed more than expected, as Paul McAuliffe TD referred to the Bill, which he voted for, as a ‘cover up’. Notably, Minister O’Gorman did apologise for his poor handling of the matter, although it was a move that didn’t protect his party and since the Chairpersons of Young Greens and the LGBT branch have both stepped down. Some Ministers have tried to reassure the public that better change will come, but with no explanation as to how.

Ways To Help:

Sign this petition: https://my.uplift.ie/petitions/repeal-the-seal-open-the-archive

Email your elected TDs and Senators to express your concern, all contact details can be found at www.oireachtas.ie

Take part in virtual protests.

Without asking for an extension on a self-imposed deadline and allowing for the proper parliamentary process on the matter, the Bill was rushed through in just one week. Again the abuse of women and children, abuse that is retained in living memory, has been swept under the carpet. It has been a gut-wrenching week in Politics, and one that has been difficult to watch unfold, but most certainly one that will not be forgotten.

Updates:

Presidents Reaction 25.10.2020

The President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, signed the controversial Bill into law the Sunday following it passed through the Houses of The Oireachtas. As other passed Bills were signed in to law on the Saturday, it became apparent that the President was slow to pass the Mother and Baby Homes Records Bill. On Sunday evening, in an unusual fashion, the President released a statement in regards to the Bill, in which he outlined his concerns. President Higgins stated that while the Bill may not be unconstitutional, it is illegal, and challenged 'any citizen' to appeal the Bill to the courts under Art. 34.3 of Bunreacht na hEireann. The statement can be read in its entirety here.

Government Reaction 28.10.2020

A lengthy statement released by Minister O'Gorman on Wednesday evening, almost one week after the Bill passed through the Dáil, has been met with cautious optimism by campaigners and survivors. The statement acknowledged the 'genuine hurt' felt by the Irish public and expressed deep regret for it, before elaborating on efforts that will be made to repair this process going forward. In the statement, the Government made promises of a victim focused approach and that survivors will be able to access their personal information under GDPR guidelines. It discussed the establishment of a national archive which will hold records 'related to institutional trauma during the 20th century', to be designed by professional archivists and historians, as well as victims, survivors and their advocates. The statement has been regarded as the right first step forward, and is hoped to live up to its promises. The Statement can be read in its entirety here.

About the Creator

Sorcha Murphy

Taking a different perspective to what life throws at me.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.