The Racial Line and its Inhabitants

Religion and Black/White relations

Religion in the Americas can hardly be separated from the concept of race since they are two of the pillars of the post-colonial societies created onto these lands. Anti-Blackness specifically as a long history in the United States and those beliefs were laced into Christian religions as well as in the tropes created to embody those racist myths about Black people. This essay will look at the ways the line between Blackness and Whiteness was handled by some religious denominations as well as by the justice system, giving a special attention to how the trope of The Tragic Mulatt* falls into it, considering mixed race bodies fall onto this line. Finally, I will also make links between the trope and certain religious groups.

The word ‘‘mulatt*’’ has been used for centuries to describe mixed people, and comes from the Latin for ‘‘mule’’, name given to the offspring of a horse and a donkey (Thompson-Miller, 2021). The Oxford English Dictionary claims that the word’s first printed appearance was in 1595 and that it might also have Arabic roots, coming from the word muwallad which can be translated to ‘‘mestizo’’ or ‘‘mixed’’ (Christiansen, 2007, p.77). The etymology of the word gains meaning when we look at the characteristics of a mule and how those were also applied to biracial people. The idea that a donkey is a less than version of a horse, in this case associating the horse to the White parent and the donkey to the Black parent, framing their existence as an ‘‘unnatural union’’ (Thompson-Miller, 2021). Mules are also sterile meaning they cannot reproduce. Biracial people can obviously reproduce but this comparison reinforces the idea that biracial people do not have parents of their own because their ‘‘mixed blood’’ makes them unnatural (Thompson-Miller, 2021). What has come to be known as the ‘‘one drop rule’’, is the belief under which one drop of ‘‘Black blood’’ ‘‘designates one as Black’’ (Christiansen, 2007, p.63), and it applies here because one of the parents being only partially Black was enough for their child to be considered as such, even if the other parent was fully White. As for the element of tragedy, it is believed to come from the fact that they will never be accepted in the world because they live in between two: the White world and the Black world. Because this word is a slur, due to its past and etymology comparing Black people to animals, further on in this paper, I will refer as the stereotype as the ‘‘Tragic M’’ trope.

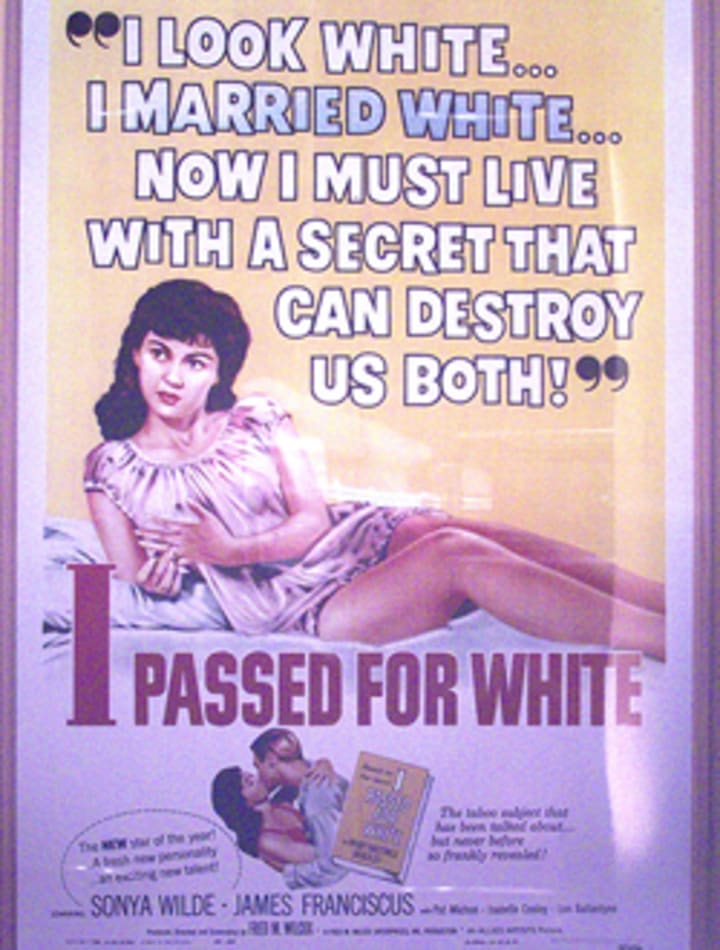

The tragic M falls in the category of racist archetypes, some other examples being the Jezebel and Uncle Tom. In literature and cinematography, she was portrayed as a woman with light skin who had a White and a Black parent. Often shown to be mentally unstable and depressed, she was tragic because no matter how light her skin was or how polished her manners were, she still had ‘‘Black blood’’ (Pilgrim, 2000). Her feelings of alienation often lead her to suicidal thoughts because she was believed to not belong on earth, meaning she could ‘‘[find] peace only in death’’ (Pilgrim, 2000). Until said peace, people of mixed race were believed to live their life ‘‘on the precipice of death’’ (Bantum, 2010, p.16). She was also portrayed as sexually promiscuous, similarly to the Jezebel, but there is an added aspect of trickery, meaning she would try and trick White men into being with her and lie about her Black ancestry; she wanted to marry a White man because she despised Black people (Pilgrim, 2000). Painted as an unstable seductress wanting upward social mobility, the M was often blamed for the sexual violence she received at the hands of White men (Pilgrim, 2000). She was believed to be selfish, abandoning her Black family to live as a White woman, reinforcing the idea that Black women are bad mothers and therefore should not reproduce, not even with White men (Pilgrim, 2000). The way she could not be accepted within White, nor Black people was used as a way to justify the unnaturalness of her existence which we could obviously link to the laws criminalizing interracial marriage and sexual intercourse in the United States. This trope also affected men though in cinematography, the stereotype was mostly attached to women.

Miscegenation laws refer to the laws that criminalize sexual intercourse and/or marriage between two people of different racial backgrounds, ‘‘from the Reconstruction era to the1960s’’ (Welke, 2012, p.279). While this paper will focus on interracial relationships between Black and White people, as well as the way half Black, half White people fit into this conversation, it is important to note that these laws applied to people of Asian and Native decent as well. These laws were obviously adopted by many states, such as Utah in 1888, but also by religious groups, such as the Mormon church (Marianno, 2015). However, even before these laws were adopted in Utah, the Mormon church excluded African-Americans from accessing certain opportunities such as priesthood (law that was repealed in 1978) and temple rituals (Marianno, 2015). Furthermore, the beliefs of White purity were also supported by the religion, therefore condoning interracial relationships (Marianno, 2015). This belief then supports this idea that mixed race people are not pure, because their Whiteness is tainted by Blackness. Many have said that religious ideals are what constructed those laws. The belief that people of different racial backgrounds had to be separated was used to justify slavery but also to oppose interracial marriage on a legal level (Davis, 2013).

This is especially important when we think about the fact that most religions condemn extra marital sex regardless, meaning laws forbidding interracial marriages were also made to condemn any type of sexual contacts between White and Black people, if they did not already. With that being said, a lot of biracial people came to life following the rape of enslaved Black women by White masters, and in this case, both the biracial child and the Black woman could not have access to any of the benefits granted by marriage or proximity to Whiteness (Marianno, 2015), which aligns with the way the Mormon church used to refuse certain status to Black members. Furthermore, before interracial sexual intercourse became illegal, biracial women were targeted for sexual violence and therefore sometime sold for higher prices during the slave trade because of their sexual value (Marianno, 2015).

Mary Douglas wrote about this idea of lines, barriers and transgression when talking about the concept of ‘‘dirt’’, saying that ‘‘dirt is essentially disorder’’, and that it ‘‘offends against order’’ (Douglas, 2002, p.2). Order and disorder are two words often used by religious groups to talk about race relations which, we will discuss later. Furthermore, Douglas more precisely describes dirt as things that are out of place, meaning things that belong somewhere and are not dirty by nature, but become dirt when they are misplaced (2002). This argument seems to be the one that was used by pro-segregation groups (some of them religious, some not), and of course, Black people, and overall, non-White people, were seen as the ‘‘things out of place’’. Similarly, one could say that the idea of the ‘‘one drop rule’’ is sustained by ‘‘ideas of contagion and purification’’ (Douglas, 2002, p.6), because it upholds the idea that one drop of ‘‘Black blood’’ is enough to make someone non-White. Her idea of disorder can also be seen as linked to the Tragic M trope when she describes dirt as being the relation between ‘‘life to death’’ (Douglas, 2002, p.7) because, as we have established, mixed race people were seen as being destined to a tragic life that would lead to death because they exist on the line, but once again, that one drop is what makes them fall into the other side.

People have used religion to justify their mistreatment of Black people or even of the White people who stand at a certain proximity to Blackness, through marriage for example. Not even thirty years ago, James Landrith was seeing his enrollment at Bob John’s evangelical university be refused because he was married to an African American woman, the institution saying that ‘‘God has separated people for His own purpose’’ and that for this reason, they did not support interracial marriage (Haynes, 2002, p.4). As for the Bible itself, passages such as the one referring to the people who built the Tower of Babel have been used to justify such stands, the example of Landrith being one of them. The letter of refusal mentioned that God would unify the world once he would return but that until then, we should live divided, as if that would help world order, which implies that mixing would disrupt it (Marianno, 2015), which aligns perfectly with Douglas’ theory (2002): Black people are perhaps not ‘‘absolute dirt’’ (p.2), but they become dirt when mixing with White people. Mormons’ use of scripture to justify their racist views was one regarding the curse of Cain who is biblically known to be the world’s first murderer (Marianno, 2015). It is said that when Cain killed Abel, God put a mark on him so that he would not be killed as a punishment for his crime, this mark being interpreted by some as darker skin, meaning people with darker skin, and specifically people of African decent, were his descendants (Junior, 2020). This argument was used by religious groups but also by pro-slavery advocates when it came to justify the enslavement of African people (Junior, 2020). The Jehovah’s Witnesses is another Christian religious group that emerged in the late 19th century (Heyward, 2012) and that has a history of anti-Blackness, specifically when it comes to the framing of Blackness as ‘‘tied to perniciously particularistic nationalist commitments’’ (p.97) and the ‘‘preoccupation with turning Blacks into Whiteness’’ (p.98). One of the ways the latter was presented is by acknowledging the humanity of Black people, not as a way to take a stance for equality, but as a way to express that God will ‘‘regenerate the world and its inhabitants by obliterating all marks of degeneracy – read as Blackness’’ (Heyward, 2012, p.99), once again following Douglas’ thesis on categories and the importance they have to some people (2002). It is also said that Charles Taze Russells, one of the founders, accepted segregation as ‘‘an evangelistic necessity’’ (Heyward, 2012, p.98) and believed that there was an ‘‘explicit articulation of the belief of the actual inferiority of Black people’’ (p.98-99). The Watchtower, in the Jehovah’s Witness’ official journal of the same name, made a statement in the late 1950s, which made it clear to say that Civil Rights would not be their priority, because they would always put God first, even if that meant leaving their non-White members behind (Berman). The event leading to this declaration was a photo where the ‘‘coloured’’ members were assigned to the gallery, separating them from White members. But regardless, a study from 1993 found that ‘‘52% of all American Witnesses[were] Afro-American or Hispanic’’, which represents the majority (Bergman, p.2). It was also said that they viewed Black suffering as a way to cultivate humility, and therefore that they should stay humble and not challenge the system though it was obviously skewed in their disadvantage (Bergman). This disinterest in fighting for Civil Rights could come from Russel himself (and therefore the Watchtower), since he believed that the original humans, the ones to which we would return to after the return of Christ, were White and spoke Hebrew (Bergman). Further into the 20th century, it seems that the tactic used by the religion was to adopt a more ‘‘colour-blind’’ approach to race in order to reduce the risk of the creation of racialized identities within the members (Heyward, 2012), also explaining why they were one of the last religious groups to be integrated in the South (Bergman).

When it comes to the more direct links between the Tragic M trope and religion, there are a few. When it comes to the Mormon church, reproduction was seen as fundamental (O. Kendall White and White, 2005), which cannot be separated from the repetitive link made between biracial bodies and their lack of fertility. Furthermore, Black people being an integral and fertile part of the church could easily be seen as an issue within a group that used to believe in White purity (Marianno, 2015). Another point is the one mentioned earlier, this belief that God has divided the world in categories using things such as racial barriers, aligns with the idea that mixed race people could only be troubled and confused because they embody this disorder, which is one of the many traits of the Tragic M trope. Therefore, biracial bodies do not embody this sense of unity (contrarily to the popular way of thinking that seems to be evolving today that claims biracial people are the ‘‘cure’’ to racism), but rather an ‘‘interruption of racial ‘‘faith’’’’ (Bantum, 2010, p.20). Mixed race people also come to unveil the false nature of race purity because they are alive while supposedly embodying both the ‘‘pure’’ and the ‘‘impure’’ (Bantum, 2010). This notion of nature being broken also fits perfectly into the idea of the mule and how its existence defies nature’s true order. Furthermore, the ways in which people born in between such lines were referred to proves the weight these categories had, saying that these bodies ‘‘display and make visible a drama’’ (Bantum, 2010, p.16), which could not be closer to the concept of the tragic M. Haitian vodou is another religion with a history of depicting biracial people in an unfavourable light. One of the many spirits within the religion is called Èzili and she has two faces: Èzili Freda and Èzili Danto (McAlister, 2000). Èzili Freda resembles the Tragic M trope by the way she is portrayed: with light-skin, childless, vain and dripping with gold (McAlister, 2000). She is also called ‘‘mistress’’ (McAlister, 2000) which is closely linked to the slavery era, the word referring to a slave masters’ wife but also to the mixed-race concubines that some White masters had, as the practice of buying them was rather common within prominent men (Williamson, 1995). Furthermore, Haiti is an important player in this conversation because ‘‘there was a large infusion of mixed-race people from Haiti’’ into the United States, specifically southern Louisiana (Thompson-Miller, 2021). In America, these biracial women were also referred to as ‘‘fancy girls’’, underlying their higher status, which aligns with the appearance of Èzili Freda (Williamson, 1995). This practice of rich White men choosing biracial women to be their concubines sometimes created a type of hatred from White women against biracial women, proving once again that mixed women did not fit anywhere (Williamson, 1995). This hatred or feeling of competition obviously did not take into consideration the harsh reality which was that these women were enslaved and therefore, these relationships were often not loving and rather quite violent at times (Thompson-Miller, 2021). Similarly, Èzili Freda was also called ‘‘the goddess of love’’ which seems quite ironic considering she is actually miserable (McAlister, 2000). In this case, it is clear that these women are deeply misunderstood, which again, could explain why in other settings they are shown as being suicidal and depressed. Èzili Freda is also said to be childless because she sold her child in exchange for jewellery, which relates to the original idea of the mule and it being sterile, incapable of producing off-springs and/or of being a bad mother, and she is also portrayed as flirtatious and tempting to men, which is identical to the Americanized Tragic M trope (McAlister, 2000). In the vodou myth, she also asked men to marry her (McAlister, 2000) which is an interesting characteristic when linked to the fact that White slave owners would obviously not marry the mixed women they would buy as concubines because it was illegal. Her energy is described as “the solo pursuit of that which is unattainable” and especially when it comes to her gender and her dream of femininity which connects her to more regular Haitian women who are also said to be incapable of having that perfect femininity that was reserved to White women (Omise’eke, 2018, p.32). Now to go back to the mark of Cain, some Black interpreters, contrastingly to what has been mentioned prior, have claimed that the mark might be associated with white skin, saying that after killing his brother, Cain would have turned white from fear and from this point on had children with white skin (Junior, 2020), which would explain the existence of White people today. Furthermore, this theory also included the idea of white or pale skin being associated with ‘‘envy and arrogance, and (…) a passion for riches’’ (Junior, 2020, p.671), which are all characteristics associated with Èzili and overall, the M trope. This example is especially interesting because it presents the idea that Cain was once Black and became White, giving him this almost mixed identity.

To conclude, it is clear that the barriers that were put in between people of different racial backgrounds in a legal sense were also present in a religious sense. As for the people embodying the transgression of this barrier, they are persecuted for representing disorder in the world and for going against God’s plan for humans. While these ways of thinking might seem frightening and old, they are not totally absent from our current world. Mixed race bodies are still marginalized, fetishized and mythicized in order to render these pejorative ideas more tangible to the people who are invested in making them stay, often in the name of keeping this godly order, but ultimately perpetuating anti Blackness.

Bibliography

Bantum, B. (2010). Redeeming Mulatto: A Theology of Race and Christian Hybridity. Baylor University Press.

Bergman, J. Jehovah’s Witnesses, Blacks and Discrimination. http://www.baytagoodah.com/uploads/9/5/6/0/95600058/jehovahs_witnesses_blacks_and_discrimination.pdf

Christiansen, A. (2008) Passing as the ‘‘Tragic’’ Mulatto: Constructions of Hybridity in Toni Morrison’s Novels. In Audrey B. Thacker & David S. Goldstein (Eds.), Complicating Constructions: Race, Ethnicity, and Hybridity in American Texts (pp. 74-81). University of Washington Press. https://doi.org/10.5860/CHOICE.45-3629

Davis, R. L. (2013). Almighty God Created the Races: Christianity, Interracial Marriage, and American law (review). Journal of the History of Sexuality, 22(1), 163–165.

Douglas, M. (2003). Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concept of Pollution and Taboo (Ser. Routledge classics). Routledge. https://doi-org.lib-ezproxy.concordia.ca/10.4324/9780203361832

Haynes, S. R. (2002). Noah's Curse: The Biblical Justification of American Slavery (Ser. Religion in America series). Oxford University Press.

Heyward, R. (2012). Witnessing in Black: Jehovah's Witnesses, Textual Ethnogenesis, Racial Subjectivity, and the Foundational Politics of Theocracy. Black Theology, 10(1), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1558/blth.v10i1.93

Junior, N. (2020). The Mark of Cain and White Violence. Journal of Biblical Literature, 139(4), 661–673.

Marianno, S.D. (2015). To Belong as Citizens: Race and Marriage in Utah, 1880-1920. [Master’s thesis, Utah State University]. All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5480&context=etd

McAlister, E. (2000). Love, Sex, and Gender Embodied: The Spirits of Hatian Vodou. Love, Sex, and Gender in the World Religions, 2. Oneworld Publications.

Thompson-Miller, R. Mulattos. International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Retrieved March 27, 2021 from https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/applied-and-social-sciences-magazines/mulattos

Omise’eke, N. T. (2018). Ezili’s Mirrors: Imagining Black Queer Genders. Duke University Press Books.

Pilgrim, D. (July 2002. Edited in 2012). The Tragic Mulatto Myth. Retrieved March 27, 2021 from https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/mulatto/homepage.htm

Welke, B. Y. (2012). Miscegenation and the Racial State. Contemporary Sociology, 41(3), 283–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094306112443511a

White, O. K., & White, D. (2005). Polygamy and Mormon Identity. The Journal of American Culture, 28(2), 165–177.

Williamson, J. (1995). New People: Miscegenation and Mulattoes in the United States. Free Press.

About the Creator

Lonely Allie .

25 year-old disabled sociology and sexuality graduate trying to change the world. Nothing more, Nothing less.

Montreal based, LG[B]TQ+, Pro-Black Feminist.

You can find me at @lonelyallie on Instagram.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.