The Intersectionality of Class and Age in the Bolivian Marketplace

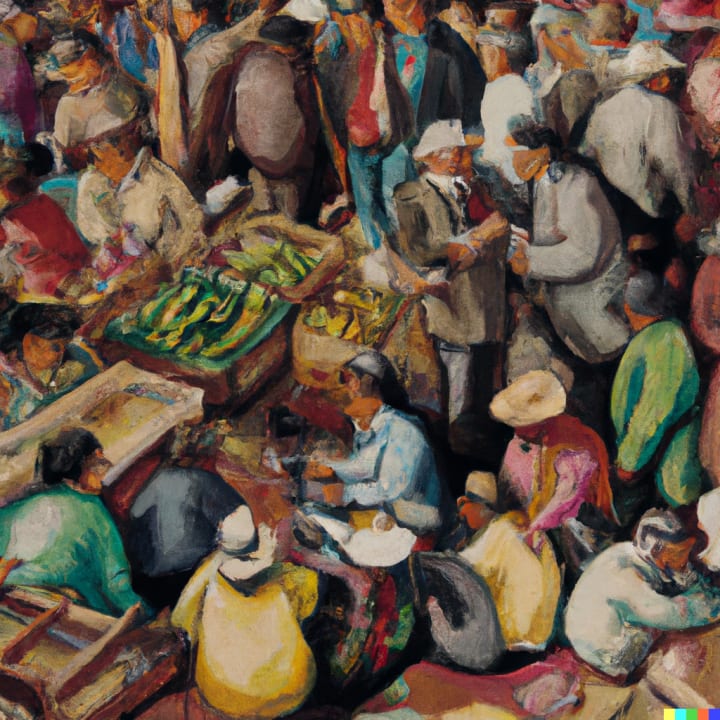

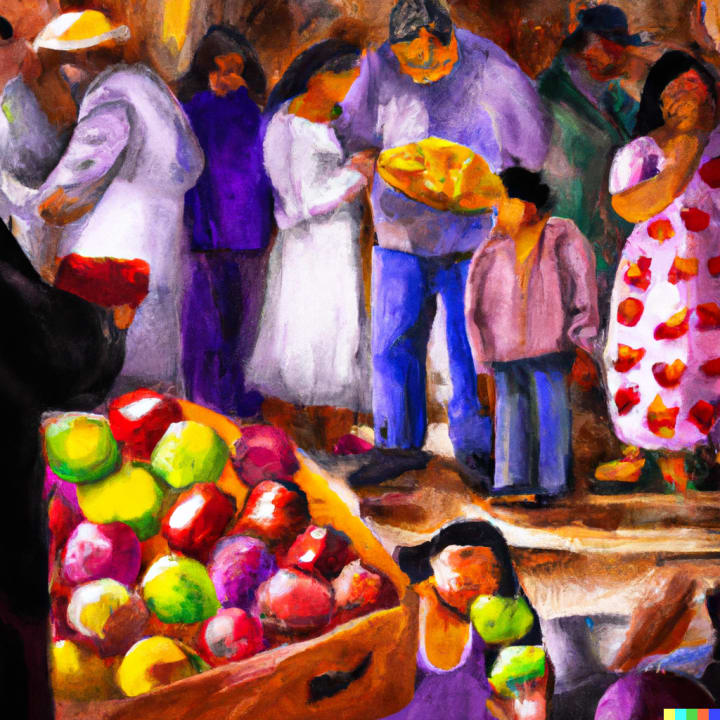

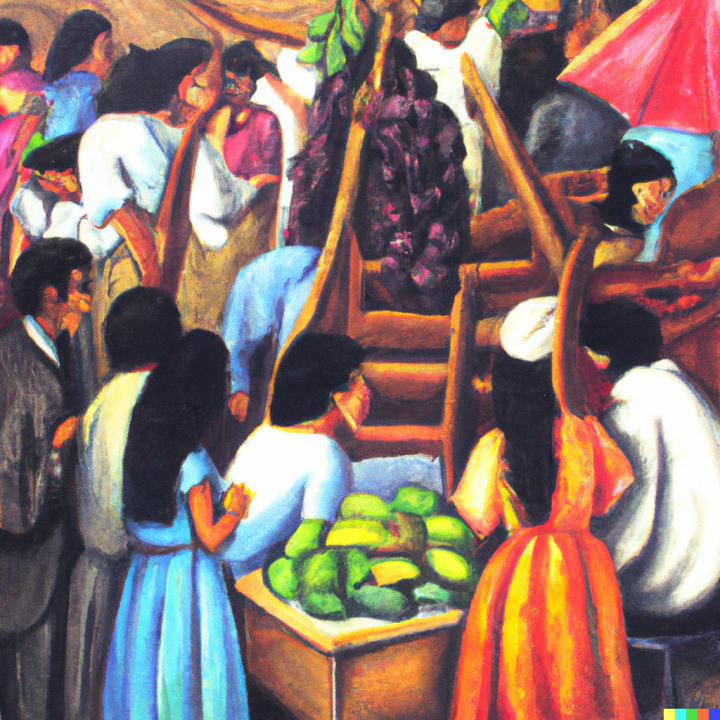

La Cancha, Cochabamba, Bolivia

“In 1918, complaints about the presence of “comerciantes minoristas ambulantes” on the streets of Cochabamba began to appear in newspapers. Writers protested against vendors “who don’t pay the patent municipal or any other kind of tax””(Goldstein 2016, 84).

Amubulantes are the most “vulnerable and economically insecure of anybody in the Cancha,” because they “suffer police raids, extortion, confiscation and harassment” (Goldstein 2016, 104). Oscar Lewis “suggested that certain ways of thinking and feeling lead to the perpetuation of poverty among the poor. Lewis argued that children growing up poor in a highly stratified economic system were particularly vulnerable to developing feelings of marginality, helplessness, and dependency…and make it difficult for them to escape poverty” (Guest 2017, 365). There is a class difference between the fijos and the ambulantes: “Thousand of long-term merchants, known as fijos, sell their wares from narrow stalls in the market’s central pavilion” (Guest 2017, 368). The ambulantes have no set selling location, they wander up and down the streets hawking their wares. This paper concerns the issue of class how class affects the day-to-day lives of the ambulantes as well as how people of different ages are treated in the Cancha. The most serious difference between the fijos and the ambulantes is that the ambulantes are treated differently by the police: “Authorities continually obstruct the work of the ambulantes, even as they turn a blind eye to the informality of the fijos and, what’s more, to the informal activities of the authorities themselves” (Goldstein 2016, 75). The ambulantes are generally treated as criminals, but since the fijos are established, legal salespeople they are respected by society and aided, not terrorized, by the local authorities. The old and the young of the lowest class are targeted by both the fijos and the police.

Both the very old and the very young are discriminated against in the Cancha. The fijos in the cancha treat ambulantes badly because they are licensed sellers with market stalls while the ambulantes do not have permits to sell on the streets. An old woman carrying herbs to sell attempts to rest near one of the fijos' stalls. The fijos abuse her verbally and pour cold water over her head. The old woman tells them " One day you, too, will get old and life will treat you as you are now treating me." (Goldstein 2016, 87-88). The fijos panic: "One of them, shrieking, declares that the old lady is a witch and accuses her of placing a curse on them" ( Goldstein 2016, 88).

The old woman is being accused of witchcraft for how she reacted towards their treatment of her. Magic is a form or power, particularly ancient rituals which are passed down through generations. The old woman was carrying a rare herb that is incredibly rare and according to Goldstein only the most legitimate mystics use in their rituals. Although the two women at the stand are in a more powerful position, since they own a legal stand from which they have a license to sell, the old woman may posses the power of witchcraft, which is viewed as real by the people in this particular culture. The old woman suffers from her intersectional position of her class and age. Not only is she considered of a lower class than the fijos, but she is an old woman and thus seen as a witch and the fijos are scared that she is cursing them and react violently.

The only thing worse than being an old ambulante in la cancha is being a young one. The one thing that the ambulantes and fijos agree upon is that the main problem in the market is the younger people: “Many of these delinquents are juveniles who inhabit the dark corners and side streets of the Cancha and lie in wait for comerciantes and their customers”(Goldstein 2016, 105). The security services “demonizes criminals and potential criminals, often young, poor and working-class black or indigenous men” (Goldstein 2016,103). The Cancha is more dangerous for lower class young people: street children are easy targets and “can be abused, removed, or even killed with impunity” (Goldstein 2016, 104).

To the salespeople of La Cancha, sharing research information with Goldstein is also a form of selling: “The research interaction, from their perspective, is a commercial exchange like any other and must include some kind of return for their participation” (Goldstein 2016, 58). The fijos and ambulantes alike feel that their personal stories are worth money and effort and sometimes they ask Goldstein to make purchases for them or from them. In order to collect data, Goldstein uses a method which he calls the “Flash interview” where he and his friend Nacho ask the fijos several short questions instead of instead of conducting long interviews (Goldstein 2016, 131).

Goldstein was able to get local collaboration from the comerciantes fijos by organizing a seminar and planning to write a book about their lives and work. Goldstein has to not only write an academic book but also help the comerciantes fijos because they are only willing to contribute to and help his research aims if he is willing to help them be more financially successful. (Goldstein 2016, 60-61). Then, Goldstein tells the ambulantes in the meet up that he is planning to write a newspaper article to that will show their side of the story and also will be writing a book about the difficulties the street vendors in general face. Goldstein eventually signs a written agreement between his organization and the group founded by the ambulantes which made their relationship more concrete. (Goldstein 2016, 119). Goldstein finally publishes the article that he has been promising to people, but he publishes it under a pseudonym because is concerned that the fijos might read it and turn against him (Goldstein 2016, 136).

Works Cited:

Goldstein Daniel M. Owners of the Sidewalk: Security and Survival in the Informal City. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Guest, Kenneth J. Cultural Anthropology: A Toolkit for a Global Age. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2017.

About the Creator

Sabine Lucile Scott

Hi! I am a twenty-nine year old college student at San Francisco State University majoring in Mathematics for Advanced Studies. I plan to continue onto graduate school in Mathematics once I am finished the plethora of courses which remain.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.