Space travel as an economy lesson

The case for making sure world leaders get the overview effect

Astronauts returning to Earth after having spent time in space often describe the emotional and cognitive impact of seeing our planet from „above”. This is the overview effect. A unique experience that produces a shift in their perception about life on earth.

”You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it. From out there on the moon, international politics look so petty.”– Edgar Mitchell

”We have this connection to Earth. I mean, it’s our home. And I don’t know how you can come back and not, in some way, be changed.” – Nicole Stott

”It suddenly struck me that that tiny pea, pretty and blue, was the Earth. I put up my thumb and shut one eye, and my thumb blotted out the planet Earth. I didn’t feel like a giant. I felt very, very small.” – Neil Armstrong

These cognitive shifts in awareness felt by the astronauts during space travel are not some emotions felt on the moment, they are profound feelings which stick with them upon their return to Earth, having the power to change their understanding on life on this planet not only at a biological level, but also with regard to aspects of everyday life, from environment to politics, resources and even economics.

In the preface of the 2009 edition of the book „Carrying the Fire”, Michael Collins describes his experience of traveling to the Moon:

When I looked back at Earth from the moon, if I could use only one word to describe the tiny thing, it would have been fragile. A totally unexpected reaction, but fragile turns out, unfortunately, to be accurate in a thousand ways. World population in 1969 was more than three billion, is now more than six, and will be eight or so when the next lunar heroes and celebrities look back. I don’t think this growth is healthy or sustainable, but our economic models are predicated on growth, they require it. Grow or die or maybe both. The dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico is now larger than New Jersey and still growing. The growth of death: a terrible thing to do to this planet. This one example makes me want to cry, and countless other catastrophes abound, some lurking in the future, many already here. We need a new economic paradigm to produce prosperity without growth. I fervently hope some of you reading this can help reverse today’s ominous trends.”

I read these lines just after finishing Kate Raworth’s book, „Doughnut Economics”, which describes a new economic paradigm, one in which all human activity happens taking into consideration Earth’s boundaries. Kate Raworth is pitching to economists the idea to redefine the notion of prosperity, while becoming „agnostic about economic growth”. Prosperity without growth - just like Michael Collins imagined while watching the Earth from the Moon’s vicinity.

The economic paradigm we live by now, based on continuous growth, is the cause of numerous effects which politicians and economists treat as „externalities”. Many of these so-called externalities – which are in fact actual consequences felt by people who were not even involved in the processes which produced them - have become the social and ecological crises of the 21st century.

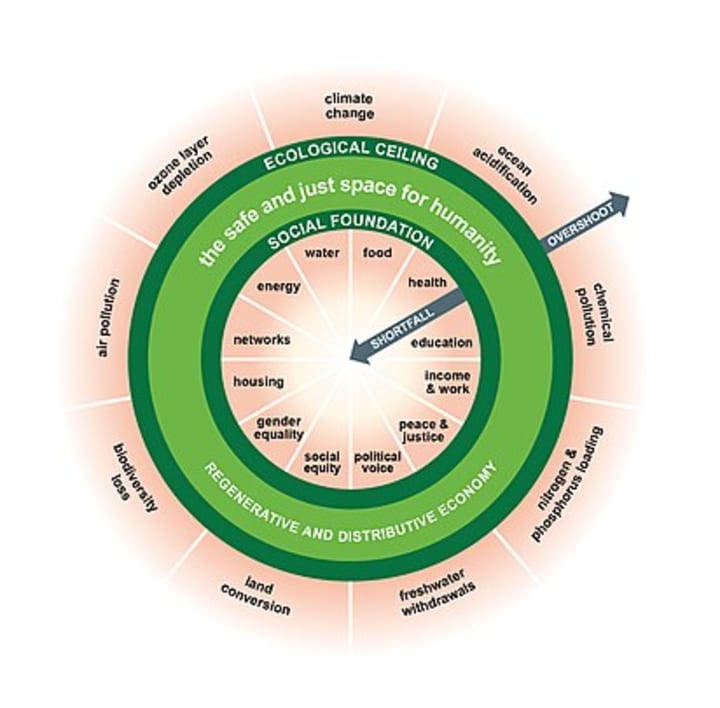

The economic model drawn by Kate Raworth looks, as the name says it, like a doughnut. It envisions a social foundation of well-being under which no one should fall, and an ecological ceiling for the pressure we apply on our planet, which we should not overshoot. Between these two boundaries – lower and upper, or social and planetary – lies the safe space where humanity should live. You can imagine it like the space between our well-being and our planet’s well-being. We need to adopt economic models which make sure that no individual is deprived of resources to ensure basic needs – food, shelter, access to education and healthcare – while also making sure that, collectively, we do not put too much pressure on the life-giving systems of planet Earth, on which we fundamentally depend – stable climate, fertile soil, protective ozone layer. In other words it is all about taking care that the activities which ensure the human well-being do not destroy our planet’s well-being.

But current economic textbooks don’t comprise these kinds of ideas belonging to 21st century economists. Economics graduates - some of whom will become decision makers in strategies and political models impacting the entire world - are still learning from economics textbooks based on outdated theories, which are rooted in the reality of other people, so much different than the reality we are living today.

Life on Earth is a natural, albeit delicate occurrence. The life of humans, animals and plants is a matter of biology and it depends on a series of conditions which must be simultaneously met. The economy is not something that occurs naturally. We, the people, create the economy. Our decisions make the economy. And we can always choose to do things differently. Economics is a question of design – it can look however we choose to – and we should choose that it takes into account all the conditions required for life on Earth to exist. And if an overview effect is what’s needed to gain the right perspective about the design of the economy, then why don’t we send policymakers to space before they get to have their say on the economic and political models we are all living with?

Or, as Kate Raworth says, just simply have them learn about Earth and her life-supporting systems. Economics means the ”art of the household management”. Understand the planetary household before you presume to manage it.

This is precisely the case Satish Kumar has brought before the London School of Economics when invited on behalf of the Resurgence Trust, to speak to students on the subject of An Ecological Worldview.

From the Ecologist:

The London School of Economics was a radical and pioneering university in the Age of Economy. But now we are entering the Age of Ecology. Therefore, LSE needs to respond to the needs of our time. LSE should become LSEE, The London School of Ecology and Economics.

There are so many signs and symptoms of damage to the ecosystems upon which the entire web of life depends. Climate change is one clear evidence of the ecological crisis. We are seeing the destruction of rainforests, the pollution of oceans with enormous amounts of plastic and the diminishing biodiversity, all at an accelerating pace. In addition, we suffer from the erosion and depletion of our precious soil from which all life derives its food. I don’t need to list all the ecological emergencies to this learned audience. Suffice it to say that at present the health of the ecosphere is in a critical condition.

Kumar argued that by not teaching ecology, LSE is teaching its students to manage something without teaching them what it is that they are going to manage. How are they going to manage something which they don’t know? And this is not only a problem at the LSE. Universities around the world teach economics without also teaching ecology, the entire syllabus emphasizing the management of money, as if money and profit are the end goals. Without taking into account the wellbeing of people and the integrity of planet Earth, the economy has been reduced to moneynomy.

From the Ecologist again:

An industrial economy is a linear economy. We take from nature, use it and then throw it with the consequence that it ends up in landfills, in rivers and oceans and in the atmosphere. We need to replace this linear economy with a cyclical economy. All goods and products must be recycled and returned to nature, without waste. This is cyclical economy.

Kumar makes the case of producing goods by using the BUD formula, which means that everything we produce and consume should have three characteristics – it should be beautiful, because beauty ignites creativity and inspires imagination. The beautiful should be useful. There should be no contradiction between beauty and utility. Form and function must always be harmoniously combined. Finally, what is beautiful and useful, should also be durable. What we produce should have a long life. So the BUD formula stands for beautiful, useful and durable, a formula which should be incorporated in the study of economics.

One example of a BUD formula found in nature, which Kumar uses in his argumentation, is the tree. Trees are beautiful to look at, while also having a great usefulness by absorbing carbon and providing shade, oxygen, nest for birds, as well as fruits for both animals and humans. And trees have a long life, some of them living for hundreds of years if unaltered by human activity. Beautiful, useful and durable.

Both Kate Raworth and Satish Kumar make the case of integrating ecology with the economy as an urgent imperative of the 21st century. Having an ecological worldview means understanding that teaching economics is incomplete without the teaching of ecology.

We define humanity as being the only species capable of imagination. However, this particular defining characteristic is the one we use the least when deciding upon important policies affecting each and every one of us. It is as though this fundamental ability of ours is bound to remain in areas such as arts, music, fictional writing and paintings, and to stay completely out of the area of “realism”, which belongs to politics and economics. As Satish Kumar says, ”there is an enormous spiritual and scientific heritage that we are ignoring. People such as [artist] William Morris, [poet] Kathleen Raine in our own time, and others. Their heritage is that of the imagination. Economics must be put in its place, imagination should be at the forefront. We are tending to go only for economics."

From the Guardian:

His insistence that reverence for nature needs to be at the heart of the world's political and social debate is the counterpoint to the insistent mantra of economic "realism" advocated and practised by government, environment groups and authorities.

Kumar has no time for realists. "Is my approach unrealistic?" he asks. "Look at what realists have done for us. They have led us to war and climate change, poverty on an unimaginable scale, and wholesale ecological destruction. Half of humanity goes to bed hungry because of all the realistic leaders in the world. I tell people who call me 'unrealistic' to show me what their realism has done. Realism is an outdated, overplayed and wholly exaggerated concept."

Instead, he seeks to learn from nature, which he calls his guide and cathedral. "Nature is realistic, and I would say that man is the only being who is not," he says. "Who else goes to bed hungry? Not the snakes or the tigers or any other animal. Nature does not need 'realistic' Tescos or Monsantos to feed themselves. Our system of 'realistic' business leadership has totally failed."

The COVID-19 pandemic could have been the chance to rethink the systems around which our lives revolve. It still can be. Change is hard and it happens slowly. But it’s the same as the economy, it doesn’t happen on its own. We make the change. History is made by the decisions we make, like the people at LSE deciding to change the name into LSEE, The London School of Ecology and Economics and start actually teaching future world leaders about Earth. Make sure they all get the overview effect.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.