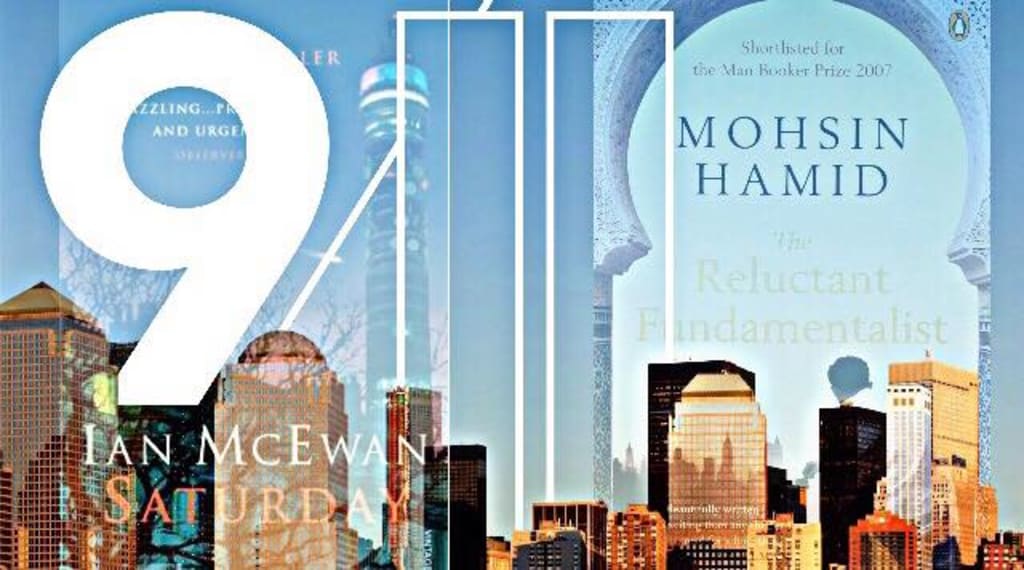

Post 9/11 Radicalization in Literature: Do Literary Works Show Modern Flaws?

An Analysis of Opposing Cultures in the Face of Devastation

Introduction

The events of 9/11 triggered a change in both the world and in literature—a change that has frequently occurred within the history of war and terrorism. The genre of "9/11 literature" has led to issues of validity and accuracy for the writers of which have addressed the devastation head on, and those who use the weakening of a western society as a backdrop to the development of their characters. The conflicts that arise within culture result in the representation of prejudices from the "victims" and contrasting bitterness of the "enemy." Depending on the author and their own experiences and thoughts of such cases, leads to the creation of a protagonist—one that we respect, or one that we find unlikeable. Within the novel Saturday by Ian McEwan, the protagonist of Perowne follows the prior, as a neurosurgeon who is reflective of his faults and open to the errors of the wider world. On the other end The Reluctant Fundamentalist by Mohsin Hamid is formed around the monologue of an individual who feels personally victimized by the Western culture, making for an uncomfortable read and unlikeable personality. The Guardian review of Fundamentalist supports this as the article addresses this narration as "epically one-sided … his developing concern with issues of cultural identity, American power and the victimisation of Pakistan" (Anthony, 2012).

Despite the differences between these two novels in their perspectives, the theme is formed around the same arguments of error and flaws of human nature, hence allowing for the comparison between their representation of the same end of the middle-eastern culture, through two polar opposite characters.

Power of Authorial influences

The power of the author in the creation of a novel plays in the decisions that they make in terms of characterisation, setting, and perspective. In the case of the two novels, perspective plays a vital role in the different approach to the same devastating event. Upon first reading the novels it is clear that one, Saturday, presents the wider view, following the typicality of a third person narration, with multiple characters voicing their views. McEwan’s own personal tone of literature means that collectively, "we have learned to expect the worst … his fiction has always dwelt at the heart of places we hope never to find ourselves in" (Adams, 2005). implying a dark context before even reading the novel. On the other end, The Reluctant Fundamentalist forms around a first person monologue of one man, Changez, adopting a style that limits the view to an individual one whilst he "maintains an outsider’s double perspective" (Olsson, 2007), never hearing from the American of which he is reflecting with. In addition to these perspectives, the author’s individual style, experiences and personal controversies also contribute to the representation of events.

Controversy of the author Ian McEwan sourced from his earlier writing of the 1970s/1980s, where criticism of his style created a reputation of negativity and the nickname "Ian Macabre." With the writings of "deranged narrators, distinguished by acts of violence and sexual obsession that included incest, sadomasochism, fetishism, infanticide, dismemberment, entombment and pornography" (Wilson, 2006), McEwan addressed issues that others in modern society wouldn’t touch due to the high degree of contention. This theme continues in the 2005 novel, addressing the source and debate, "on a specific and momentous day, February 15, 2003, the day when hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets of London to protest the imminent war on Iraq’ Banville" (2005), cited in Bookmarks (2017). McEwan is clever in his addressing of worldwide issues, no matter how controversial, through downscaling the effects of one family, with critics supporting his attempts of reflection, "Saturday catalogues the local only in order to focus on the global" (Lawson, 2005).

The social contexts of McEwan’s life meant he was sensitive to the effects on the foreign country, having seen their communities first hand. Whilst born in Aldershot, he spent most of his childhood in East Asia, Germany and North Africa (including Libya) following his father who was an army major, until he was 12 when his family moved back to England. Historically, Libya and Iraq have shared close foreign relations, until June 2003 when Libya announced the break of diplomatic ties and the closing of its embassy following the US-led invasion of Iraq (AFP, 2012). This close connection in McEwan’s life means that his view of events such as the Iraq war may be less clouded by Western judgement and share a broader view from both sides. The third person narration of the novel allows for McEwan to express his own opinions, but without fundamentally flawing the basis of the novel through bias. An example of this is in his presentation in the reality for the foreign country, particularly the negatives of an extremist lead region, ‘Beatings, electrocution, anal rape, near-drowning, thrashing the soles of the feet. Everyone, from top officials to street sweepers, lived in a state of anxiety, constant fear.’ The suggestion of an abusive, criminal totalitarian state described through listing by Perowne in the early parts of the novel shows McEwan’s own personal disapproval of such a regime, of which he has previously been criticised for verbally addressing. In 2008, McEwan spoke out against Islamism for the creation of a society in which he ‘abhorred’ by a minority who preach violent jihad. He also addressed the fact he grew up in a Muslim country, Libya, and so experienced the more positive, ‘dignified and tolerant’ Islamic culture (Wikipedia, 2018). By using the blunt, extreme violence as threats to the foreign culture, McEwan is expressing the negative approach whilst also ensuring the clear fact that not everyone follows those ideas, with a range of those from ‘top officials’ to ‘street sweepers’ falling as victims of the violent society.

On the other hand, Mohsin Hamid, from Lahore Pakistan, does not carry the same controversy as McEwan has in the past, however their views of a strict regime do not differ in their negative connotations. Much like McEwan, Hamid addresses the strict nature of the Muslim community, specifically in the freedom of gender. "The men and women—yes, the women, too—of my household are working people." The embedded clause emphasising the ability of women to work shows that this is not a common aspect of a middle-eastern family, and by Changez providing this additional information to develop his storyline we get an insight into the reality of a foreign regime. Hamid is also addressing the assumptions of the Western culture in Changez justification in his statement, having to confirm what he has said to the American as it does not follow the ‘norm’ of a view on the foreign country.

In an interview conducted in 2010 Hamid also had his say in the restriction of those with a "Muslim-sounding name" in terms of voicing opinions, stating it is "hard to be someone with avowedly secular politics and liberal values writing in Pakistan" (Singh, 2010). As a writer from Pakistan, Hamid knows first-hand how this lack of free-style and theme to express your own personal opinions can limit the writer to specific topics of discussion. Therefore, The Reluctant Fundamentalist typically follows the addressing of religion and the rejection of external opinions through the characterisation of Changez and his negative, bitter perspective toward the Western society.

Sensationalism

Similarly to authorial influence, the effects of media and common perceptions can lead to wrongful assumptions and misinterpretation in the representation of an event or culture. Sensationalism refers to the presentation of stories in such a way that attracts public interest, normally at the expense of accuracy in details.

Both Saturday and Fundamentalist address directly the effects of media on the characters and on the society they are living within, and how the leading of an entire culture can cause human flaws.

Before sensationalism comes fiction and literal fantasy, as metafiction in literature often shows. The awareness of reading a fictional statement, and the life of a made up character, often means that readers dismiss aspects of opinions as simply those of fiction, therefore making them unreliable. However, in the case of media and politics, it is difficult to assess whether what it being shared, is representative of the truth, and this is when sensationalism can cause issues in the development of an individual’s view. The character of Perowne within Saturday addresses metafiction as a criticism, "it interests him less to have the world reinvented: he wants it explained. The times are strange enough. Why make things up?" The rhetorical question implies the disregarding of entire literature, built upon "making things up." It also brings into question what is the meaning of literature, when the real world is already created around confusion and questions, why source more through fiction? Lawson of The Guardian implies that the novel is "One of the most oblique but also most serious contributions to the post-9/11, post-Iraq war literature, it succeeds in ridiculing on every page the view of its hero that fiction is useless to the modern world." Therefore highlighting the complex narrative in questioning the power of literature, within a literary work.

Additionally, in Saturday. media influences are addressed head on, particularly in terms of the Iraq war and the criticism of self-denial in characters being swayed by their media environment. Firstly, the setting of a plane that is crashing through the London sky creates the backdrop for a dramatic storyline, but this is quickly reduced to irrelevance in the eyes of the western world due to the simple "mechanical error." This idea plays on the interest of the public and how suspense within media stories attracts attention, with the news story about the plane falling short—"a disappointing news story—no villains, no deaths, no suspended outcome." This also plays a role in Fundamentalist as Changez expresses unreliability in his narration, "I cannot recall many of the details of the events," before concluding "…it is the thrust of one’s narrative that counts, not the accuracy of ones details." Therefore both novels play on the theme of an "exciting narrative" rather than the accuracy of details, inevitably causing issues of reliability.

The denial of characters is prevalent in Saturday, but the reflective nature of the novel allows readers to be aware of these flaws. For example, "Does he think he’s contributing something … reading more opinion columns of ungrounded certainties … For or against the war on terror … Does he think that his ambivalence … excuses him from the general conformity?" This implies that Perowne is flawed in his belief that by learning more about the current situation of the world, and having a more mixed" view as to the validity of such actions, will allow him to distance himself from the conformity of the Western world. By adapting a character with a middle-eastern origin, now living in a Western country McEwan is addressing the "difficulties of representing the uneasiness plaguing the consciousness of 21 century citizens of Western nations in the aftermath … of which has defied representation and understanding within the Western cultural imagination" (Michael, 2009). Additionally it is stated, "He lives in different times—because the newspapers say so doesn’t mean it isn’t true," which implies the loss of information in media presentation, possibly due to the "plague" of the conscious Western world in showing the Muslim community in a negative light. Overall, the narrative of Saturday is led by assumptions and external opinions, with ‘worst-case guesses that become facts through repetition’ creating a culture that is controlled by a perspective formed around snippets of media coverage and articles.

The Reluctant Fundamentalist contrasts Saturday by the more bitter perspective and portrayal on the power of media. Whilst in Saturday the creation of opinions by external influences only assists in the development of plot and the omniscient reflection of characters, in the case of Fundamentalist it is instead the suggestion of Western flaws in allowing society to shift their opinions, causing a very personal, negative effect on him. At one point in the earlier part of the novel Changez admits that whilst what is being said of his home country isn’t distinctively wrong, the summary of knowledge and the application of this is more the issue than media itself—"There was nothing overtly objectionable in what he had said; indeed, his was a summary with some knowledge, much like the short news items on the front of The Wall Street Journal … but his tone …it’s typically American undercurrent of condescension." This suggests that ‘short news items’ resemble the knowledge of individuals, with the missing of details and fragmented images, but more importantly the adoption of an American typicality leads to the mistreatment and patronizing of those from his culture. Changez also comments on "The rhetoric emerging from your country … not just from the government, but from the media and supposedly critical journalists as well," implying that the events of 9/11 caused a change in the world towards the lack in reflection on their relations to those who have attacked them, and instead the creation of overall negativity with global impacts: "you were unwilling to reflect upon the shared pain that united you with those who attacked you … so that the entire planet was rocked by the repercussions of your tantrums." Within the telephone interview of Hamid he suggests this change in approach by causing "a spark in the world" due to the change in the "world narrative" and therefore the indirect "reflection in literature" and the world post 9/11.

Finally, Changez plays a role in addressing and overcoming the effects of sensationalism as he rejects external opinions due to his personal experience in the foreign country. Whilst he prefers ‘not to watch the partisan and sports-event-like coverage’ of sophisticated American weaponry against ‘ill-fed Afghan tribesmen’ Changez is avoiding the amped up, insensitive Western approach of war on the middle-east and the inequality of ability to "fight back." He also uses his local knowledge to contradict what is presented in media—"we were not the crazed and destitute radicals you see on your television channels but rather saints and poets" suggesting a depth in culture through religion and creativity, rather than the violent and restricted regime that is often shown in media due to the need for an ‘interesting story’. Critics of the novel have stated that ‘One of the novel's notable achievements is the seamless manner in which ideology and emotion, politics and the personal are brought together into a vivid picture of an individual's globalised revolt’ (Anthony, 2012). This therefore supports the nature of Changez’s character in rejecting the ‘norms’ of the modern world as fact, and rather allowing his own perceptions of the contrasting ‘emotion’ and ‘politics’ to lead his view of both the western and middle-eastern culture.

To Learn from History

Social contexts of the world are always formed by a development in history, particularly in war. The discrimination of minorities has been present since the creation of man, with the last 100 years having a particular impact on our generation. Aspects of these 100 years have played a role in impacting history, particularly in developing acceptance of others different from ourselves. Key events have included the end of the Derby day protest of 1913, when Emily Davison, a suffragette, threw herself in front of a horse to protest for woman suffrage, the invasion of Poland in 1939 of which was an aspect of the six year devastation in the slaughter of Jews and other minorities by Nazi Germany in WW2, the erection of the Berlin wall in 1961 and the fall in 1989, and Martin Luther King’s, "I have a dream" speech in 1963 for American Civil rights (Manaal, 2015). References throughout both novels of events from the past are used to develop the plot and aid in the characters own personal progression.

There is a noticeable difference between the two novels in their allusion to historical events. Whilst Saturday focuses on events that have affected the Muslim culture, comparing the devastation of extremism with past dictators at the source of mass murder, Fundamentalist addresses general history and particularly how America has conducted itself within conflicts. Changez also shows a development of countries in contrast to the past, with Saturday contradicting this and questioning if the world has fundamentally changed.

The initial allusion to war in Saturday refers to events ranging from 1990 to 2003, all with connections to Muslim conflicts with the Western world. This starts with the Gulf war, otherwise known as ‘Operation Desert Shield’ which sourced from the decisions of Saddam Hussein in invading Iraq’s neighbour, Kuwait—"Troops mustering in the gulf." Saddam has been labelled as a "brutal dictator, who for 11 years had enforced a violent regime that murdered and tortured without hesitation" (20th Century Battlefields S01 E08 1991 Gulf hd full, 2015). He found a solution for the Iraqi bankruptcy formed by the regime in the neighbour of which was ‘floating on oil’, holding ten percent of the worlds reserves. However, Saddam underestimated the fact that ‘western leaders didn’t have the stomach for a middle-east war’ and therefore caused the retaliation of USA and the British at the fear of invasion of Saudi Arabia, which would lead to the access to half of the world’s oil, with ‘one of the biggest deployments of troops since WW2.’ With reference to this Western vs Middle-Eastern conflict, McEwan is suggesting the lack in change from past to present, problems between culture is not a new thing. Perowne continues to allude to conflicts with ‘tanks out at Heathrow ... the storming of the Finsbury Park mosque ... terror cells around the country’ which relates to multiple responses to terrorism in the UK during 2003. Therefore, the novel is expressing an overwhelming presence of war and conflict and as to how the history of these events have shaped the current world. ‘The 90s are looking like an innocent decade’ shows this as the occurrence of 58 wars in the 10 years seems to be minuet in comparison to the scale of conflict in the 21st century.

Saturday also uses well known dictators to contrast the past and present severity of conflicts, "What was their body count, Hitler, Stalin, Mao? 50 million, a hundred? If you described the hell that lay ahead…would not believe you." Collectively, Hitler, Stalin and Mao were the cause of potentially over 100 million deaths, therefore by stating ‘the hell that lay ahead’ Perowne is implying that to those from the past devastation, our current world seems more severe and frequent of mass deaths of communities. Furthermore, the allusion to the novel Two Hours that Shook the World by Fred Halliday precipitates the events of 9/11 as a landmark in modern history, just like past wars and experiences—‘Fred Halliday's book ... looked like a conclusion and a curse; The New York attacks precipitated a global crisis that would, if we were lucky, take a hundred years to resolve.' Halliday implies that 9/11 has triggered a military, economic and cultural backlash worldwide. This backlash of which will be felt by Perowne and his children, making it extremely personal to the narration of the novel, ‘Henry's lifetime, and all of Theo's and Daisy's—and their children's life-time too.’ Whilst Perowne will have experienced past discriminations, his children and grandchildren will experience the future traumas.

Overall, Saturday concludes that, "The world has not fundamentally changed" as societies talk of war in a way that is purely for gratification rather than the belief of importance—"Talk of a hundred-year crisis is indulgence." The frequency of devastation in the modern world makes the current generation numb to the severity, "catastrophe" and "mass fatalities," "chemical and biological warfare" and "major attack" have recently become bland through repetition, brushing new controversies off as the "next thing" to move on from. Perowne expresses this view through "There are always crises, and Islamic terrorism will settle into place, alongside recent wars, climate change, the politics of international trade, land and fresh water shortages, hunger, poverty and the rest," comparing the death of minorities and innocents to more irrelevant notions of ‘international trade.’ Therefore McEwan is suggesting that rather than learning from history and the mistakes that others have made, we instead set them in the backs of our minds as another ‘crisis’ that our governments with eventually solve.

Hamid conflicts McEwan in his approach to the past, with loose references to general human history and the formation of power in countries, particularly Pakistan and America. This history forms the negative perspective of Changez in questioning human nature in the face of a conflicting culture. The character longs for change ‘in a period of great uncertainty’ whilst he believes others to be stuck wanting something that has never existed, a ‘possibility of progress while others longed for a sort of classical period that has come and gone, if it had ever existed at all.’ The character or Erica, Changez love interest, represents this side of the ‘stuck’ world in her downward spiral and eventual admission into a mental institute by the grief of her boyfriend’s death. The New York Times has criticised that ‘This part of the story seems a bit too convenient — Erica’s obsession with the past engineered to dovetail with America’s nostalgia and with Changez’s yearning for a lost Lahore’, therefore building on the analysis of his narration, providing a very personal experience of both approaches to the past, through Erica’s story. He also addresses the history of Pakistan in comparison to America, with a power leaning towards his home country, a power that is now lacking whilst America develops. By focussing on cultural history, "We built the Royal Mosque and the Shalimar Gardens in this city, and we built the Lahore fort … and we did these things when your country was still a collection of thirteen small colonies…" Hamid is removing all elements of economic development in history. By removing this variable he is leveling the two cultures, suggesting a powering advantage in the hands of the Middle-east due to the richness and origins of their history.

Overall, the focus on American mistakes in history is shown through the bitterness of the foreign narrative, of which Changez "resents the manner in which America conducted itself in the world." He also implies that the power of American sources from the interference in foreign affairs that they do not need to involve themselves in—"your country’s constant interference in the affairs of others" but do so for the status of ‘doing something’ rather than letting other countries fight their own battles. This list consists of ‘Vietnam, Korea, the straits of Taiwan, the middle east, and now Afghanistan’ all of which America had a strong hold on the duration and outcome of conflict. As stated in the 2012 guardian review, ‘he is the embodiment of the argument that says that America has created its own enemies.’ Hence, the allusions to creation of such enemies, within wars that they had no real basis in being involved in.

However, both novels are flawed in the sense of not learning from history in their response to 9/11. The fact of it being ‘too soon’ to write an accurate account of events, emotions and opinions is in the contrast of past successes (R.B, 2011). Catch 22 is considered to be one of the best novels of WW2, not written until 1961, 16 years after its conclusion. Therefore it has been criticised that due to 9/11 being ‘a day in the life of the world’ the aspect of personal memories play a role in any writing in regards to the event. ‘It is hard to relay an event that many people still remember so clearly,' making the overall narration of the two novels questionable.

Selfish Fears

The fear of the Islamic state and the ‘radicals’ created by violent regimes and fundamentalism surface in Western culture when approached by a man or woman of the associated faith. The culture of fear has been suggested to source from the modern approach, ‘Stories of beheadings, bombs and genital mutilation … the images and narratives that continue to dominate Western media’s coverage of Muslims, selling the message that they are perpetrators of savagery, deprivation and torture’ (Fahd, 2017), leaving little room for interpretation. Whilst in Saturday this distinct fear isn’t addressed in the extreme responses by society to a man of middle-eastern origin, Perowne instead addresses his own fears sourced from the modern perspective. Fundamentalist on the other hand follows the basic norm of discrimination through the fear of Changez’s ‘nervous American’ listener.

The vague mention of possible impacts on Perowne arises indirectly in his work-life, ‘Henry Perowne loses a number of cases each year … patients don’t like what they see but are ignorant … some note the hands, but are placated by the reputation.' Whilst the initial statement doesn’t necessarily imply a religious fear or discrimination by his patients, the supports of the later ‘reputation’ confirms that these losses are not simply due to his level of skill in being a neurosurgeon. This entire statement expressed by Perowne is however a series of contradictions, with ‘placated’ implying a calm and accepting approach to his reputation, and yet he still loses cases. While there are no answers within the novel as to why his patients dismiss his ability, it could be implied that the reputation of his assumed religion and the ‘ignorance’ of his patients cause them to act towards him in a calm demure, for fear of his reaction to their rejection. Perowne himself addresses his ignorance of, ‘Misunderstanding … the details he half-ignored in order to nourish his fears’ as it becomes ‘general all over the world’, therefore it is not far-fetched to believe that his patients fall under the same discrimination and assumptions, when he himself falls victim to it. In criticisms of religious-lead fears it has been asked ‘Why are we not talking about the pervasive and relentless impact of political and media discourse in training people to fear Muslims?’ (Abdel-Fattah, 2016). By Perowne showing the same character as those in his society, the extent of this ‘pervasive and relentless impact’ is far-reaching, training even those who have personal standings in the religion, to fear events that could be related to acts of terror. In addition to this, an allusion to a thought experiment conducted by Schrodinger, ‘He told himself there were two possibly outcomes—the cat dead or alive. But he'd already voted for the dead...’ implies that in a state of uncertainty, people often conclude on the negative outcome despite no evidence telling them so. Therefore, when a plane is crashing through the sky above a city, it is instinct to assume terrorism rather than technical faults.

The fear presented in Saturday, however, is based around Perowne’s dismissal of his daughter’s bold opinions as they conflict his own view. A genetic flaw is suggested to be the cause with ‘poison in his blood … fear and anger, constricting his thoughts,’ making it entirely personal to Perowne rather than that of social contexts. In the nature of the novel, his character is reflective of such flaws by questioning his own intentions—‘he wonders why he’s interrupting her, arguing with her, rather than eliciting her views’ therefore addressing his fears head on, in the sense that controversial views cause debate. Saturday summarises the fear of opinions rather than of a culture, or rather, characteristics of a culture.

Fundamentalist takes on the more stereotypical approach, with the opening line of the novel highlighting the physical characteristics at the source of Western fear- ‘Ah, I see I have alarmed you. Do not be frightened by my beard: I am a lover of America.’ This bold, matter of fact introduction addresses the issue from the get go, that a man with tanned skin and a beard must verbally say he loves America in order to have a conversation without fear. Despite this opening line, the duration of the novel is filled with the same fear over small details that are otherwise irrelevant if not found in a foreign backdrop. Additionally the structure of the characters in the novel plays a role in expressing the modern approach to conflicts, with the ‘nervous American’ playing the role of typical fear, whilst Changez works to highlight and dismiss the stereotypes. Frequent interruptions in the frame-narrative by Changez emphasise the responses by the American to their present context, within a café in Lahore, Pakistan- ‘Ah, our tea has arrived! Do not look so suspicious. I assure, sir, nothing untoward will happen to you…if it makes you more comfortable; let me switch my cup with yours.’ The fact that the American even considers the possibility that his tea may be a cause for suspicion is highly irrational, but Changez’s suggestion to ‘switch my cup with yours’ in its relaxed approach implies that this irrationality is all too familiar. The role of the American has however been criticised as the power by only Changez narration- ‘Unstated actions and statements must therefore be inferred only from Changez’s responses—much like a stereotypical TV sitcom phone call extended to the length of a novel’ (Engl631, 2014) and therefore the reliability of such statements cannot be agreed or denied for following the ‘stereotypical’ approach of modern entertainment.

The American is also criticised by Changez through his misplaced fear in their Pakistani waiter, of who Changez comments ‘puts you ill at ease’. The physical features of the waiter contribute to this response by the Westerner as he carries a ‘hardness of his weathered face’ that makes him intimidating to a man without the knowledgeable context. Changez however quickly puts this misplaced fear in place by expressing explanations for fellow countryman- ‘he hails from our mountainous northwest, where life is far from easy… his tribe merely spans both sides of our border with neighbouring Afghanistan, and has suffered during offensives conducted by your countrymen.’ This justification in the waiters suffering at the hands of America shifts the fear from middle-eastern origin to Western, suggesting that while the American may fear the foreign country, inevitability it is the foreign locals who should fear the American, as they share close loses by his country. The statement also shows that fear derives from what we don’t understand, not being aware that ‘life is far from easy’ for individuals of a different region leads to the discrimination of faith and country.

Reflection VS Bitterness

The approach to the narration of a novel can lay grounds for the ongoing perspective of the reader throughout the storyline. The author may aim to highlight current issues in the real world, to make a difference and voice their own opinions, or they may choose to criticise reality. Saturday is an incredibly reflective novel, with the characterisation of Daisy, Perowne’s daughter, playing a vital role in this, and while Fundamentalist takes a more bitter approach, there is still reflection in the outline of the modern world.

The initial reflection by Perowne in Saturday comes in the analysis of being a passenger on a plane. He alludes to a collective calmness in flying, but only due to the surrounding people- ‘you submit to the folly because everyone else does. Your fellow passengers are reassured because you and the others around you appear calm.’ This theme of vice versa in the fact that you feel calm because those around you are calm, and those around you are calm because you appear calm, creates a confusing loop of responsibility; That those around us play a role in how we react individually. This could be a vital awareness in any event of stress or conflict, adding comment on the fact that societal aspects contribute to personal mindset, implying a lack of personal control. Perowne also suggests an inevitability of terrorism at the creation of one region, Iraq, of which he calls a ‘natural ally of terrorists, bound to cause mischief at some point’, followed by the dismissal of the countries relevance as he suggests it ‘may as well be taken out now while the US military is feeling perky after Afghanistan.’ The sarcasm in classing America as ‘perky’ after being at war dismisses the severity of the situation, therefore indirectly addressing issues in lack of care for assumed connections between terrorism and foreign countries. The Afghanistan war gained footing in 2001, after 9/11, when George W Bush ‘authorized the use of force on those responsible’ (CFR, 2017). It was publicly assumed that al-Qaeda were the cause, and that Osama bin Laden had residence within Afghanistan, therefore the aim of the war was shaped to ‘dismantle al-Qaeda and deny it a safe base of operations in Afghanistan by removing the Taliban from power’ (Wikipedia, 2018). Despite the effective dismissal in the novel, the importance of the Afghan war is that it is the longest war in United States History, makes its vague mention one of reflection of errors.

Political reflection plays a prevalent role in Saturday, especially through the character of Daisy, who adapts a controversial role of addressing the validity of the oncoming Iraqi war. While her father takes a more ‘stand back and watch it happen’ approach, Daisy herself takes part in protests occurring in London and brings suggestions as to why a country with no ties to al-Qaeda has become the target of military force. The most important quote for the entire duration of the novel is this argument- ‘You’re saying we’re invading Iraq because we haven’t got a choice…You know very well these extremists, the Neo-cons, have taken over America. Cheney, Rumsfeld, Wolfovitz. Iraq was always their pet project. Nine eleven was their big chance to talk Bush round…But there’s nothing linking Iraq to nine eleven, or the Al-Qaeda generally…doesn’t it ever occur to you that in attacking Iraq we’re doing the very thing the New York bombers wanted us to do- lash out, make more enemies in Arab countries and radicalise Islam.’ The reference to US political figures Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfovitz brings an analytical approach to decisions made by the White house, to the power of a group of people with a want to control a foreign region. Whilst from 2001 to 2005 Wolfovitz served as U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense reporting to U.S. Secretary of Defense, Rumsfeld (Wikipedia, 2018), Cheney was the 46th Vice President (Wikipedia, 2018). All three men carried individual public criticisms for their lack of evidence and care for severity in the approval of the Iraq war. Wolfovitz was gunning for the war due to the fact their ‘brittle, oppressive regime that might break easily—it was doable’, Cheney dismissed the lack of public confidence with ‘So?’, whilst continuing to allege links between Saddam and al-Qaeda despite their being ‘scant credible evidence that Iraq had any significant collaborative ties with Al Qaeda’, and Rumsfeld suspiciously predicted an ‘event that would occur in the world that would be sufficiently shocking’ (Wikipedia, 2018), the morning of 9/11. These clever allusions to specific powers that played a valuable role in the validity of war leaves the readers questioning the reality- the inevitable ‘radicalisation’ of Islam. The reflection of Daisy in the fact the Western world had a choice, but still chose to invade Iraq, means the reflection of the readers, that there are extremists on both sides, not just by religion but by the power that can be obtained. This awareness by the effect of McEwan has been considered to be the cause of severe abuse, such as "It didn't seem right to infest the world with any more copies of Saturday, so mine lies buried in the local tip, along with the rest of the toxic waste’ (Evening standard, 2009), of which the Evening standard stated was the outcome of ’unthinking class-antagonism and political fault-finding, I am sure.’

Fundamentalist contrasts Saturday in its bitter approach to 9/11, as Changez shares first hand his dark and controversial reaction to the downfall of America. Hamid uses possible authorial intrusion as a fact of warning to the reader, clearly aware that what he is about to write, may be classed as unacceptable to a particular audience—‘I ought to pause here, for I think you will find rather unpalatable what I intend to say’. When it is seemed to have no objections by the observer American, Changez proceeds to recall ‘I stared as one-and then the other- of the twin towers of New York’s World Trade Centre collapsed. And then I smiled. Yes, despicable as it may sound, my initial reaction was to be remarkably pleased.’ The embedded clause used shows a sense of conscience, making the bitterness of Changez in smiling at the death of innocents, reasonable in terms of his personal context, being from a country that has been threatened by America. Whilst admitting his thoughts were not with the victims at the time, the figurative mindset in, ‘I was caught up in the symbolism of it all, the fact that someone had so visibly brought America to her knees…Do you feel no joy at the video clips-so prevalent these days-of American munitions laying waste the structures of your enemies?’ suggests he finds a sense of beauty and calm in the destruction of an ultimate power. The rhetorical question also provides a very personal insight into Changez mind, of which Hamid had ‘offered one character’s rather forceful critique of America, but that did so from a standpoint of enormous affection’ (Eads, 2010). Therefore, the bitterness of Changez is presented as somewhat justified, as Hamid insists his intention are simply to ‘start a conversation’ rather than cause a conflict between the Middle-east and the West.

Conclusion

In my initial analysis of the two novels I perceived the outlooks on disaster and acceptance to be incredibly different. Simply from reading Saturday you get the sense that something is trying to be done in terms of questioning and resolving the mistakes that people in the past have made. Perowne himself suggests ‘This could be a chance to put that right.’ In regards to a century’s long conflict by the promises of Western support, and the let-down of the Middle-East when past agreements haven’t been met. In 1991 the Americans gained the trust of Iraqi locals, for them to then be betrayed, leading to slaughter by the dictator that they have been promised the downfall of. The reasonable response would be to view them as ‘the enemy’, much like in Fundamentalist, at their exploitation of weakness by the foreign power. ‘Saturday however adopts the wider approach, with it being commented by Adams that 'the author's mature attention illuminates equally everything it falls on.’ Therefore, I conclude that neither novel can be classed as ‘bitter’ or ‘correct’, but instead developmental on a genre of literature that has gained footing over the last 17 years, ‘9/11 Literature’. Cultural background will always play a significant role in the formation of a novel, and whilst to a Western reader the comments within Fundamentalist may be classed as outrageous and far-fetched, the reality is that if you have personally experienced the torture of the people around you, you are bound to have negative outlooks on Western aspects of life. When you have lost at the hands of an external country, you can rightly feel like the victim.

About the Creator

Caitlin Askew

Love for Literature- Writer since forever. Student studying Literature and Publishing. I have a strong belief that if a book doesn't make you feel something, it's not the right book.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.