Is sustainability equal?

Confronting the complicated history and direction of the sustainability movement.

Last year at a sustainability fair, I tested students from the University of Tennessee on their knowledge of environmental leaders. They were asked to pick from a group of 16 influential environmental leaders from around the world and match their face to their name and accomplishment. Out of those 16 environmental leaders, 4 were white.

This game was played over 100 times, and only a few students were able to name leaders that were people of color on the list.

Immediately most students were able to name Greta Thunberg or Al Gore, but as the faces of the leaders got browner the guesses became fewer in number. People began to point to the picture of the African woman and say things such as, “I guess she’s the lady with the African-sounding name.”

This lady with the “African-sounding name” is Wangari Maathaia, not only a famous international political and environmental activist but also the first African woman to win a Nobel Peace Prize.

Why do more people know the face and name of a Swedish girl that is just getting started in her activist career over a woman that has been making waves in environmental justice for over 50 years?

It’s because our sustainability is not intersectional.

First, let’s break down what intersectionality is. YW Boston, an organization dedicated to ensuring social justice, explains it as “… a framework for conceptualizing a person, group of people, or social problem as affected by a number of discriminations and disadvantages. It considers people’s overlapping identities and experiences in order to understand the complexity of prejudices they face.”

In other words, intersectionality is considering perspectives and issues from people of all walks of life, whether it’s race, religion, sexuality, ability, sex, and so on. The focus is on inclusion and diversity.

For many people, intersectionality is often associated with a recent wave of feminism called intersectional feminism, which shifted the focus to include a more diverse audience as the movement had previously been catered to and more focused on white women. Intersectional sustainability follows this same trend.

In the past and still seen today, environmentally-consciousness was afforded to and seen as something that was for white, rich, and more privileged people. Our environmental justice history is overflowing with cases of prejudice, and even places like National Parks were something that people of color were not privy to.

Long-running environmental activist organizations like the Sierra Club, the Nature Conservancy, the Natural Resources Defense Council, The Wilderness Society, and others have acted in prejudice ways. This prejudice has seeped into all aspects of the environmentalism movement and continues today, which is a critical problem since minority and low-income communities are affected by climate change and toxic environments at a much higher rate.

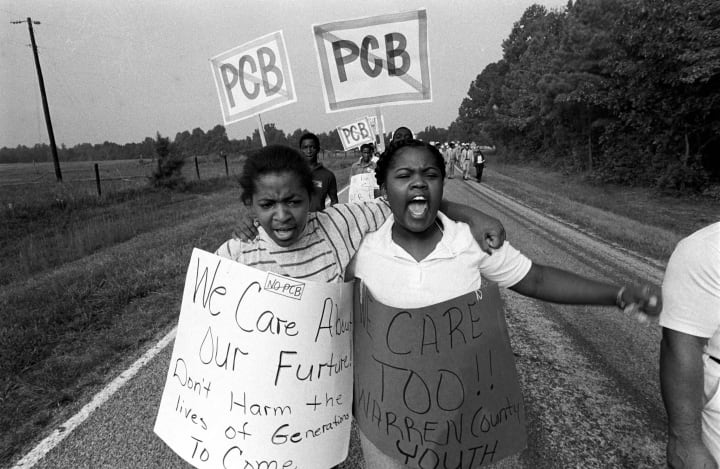

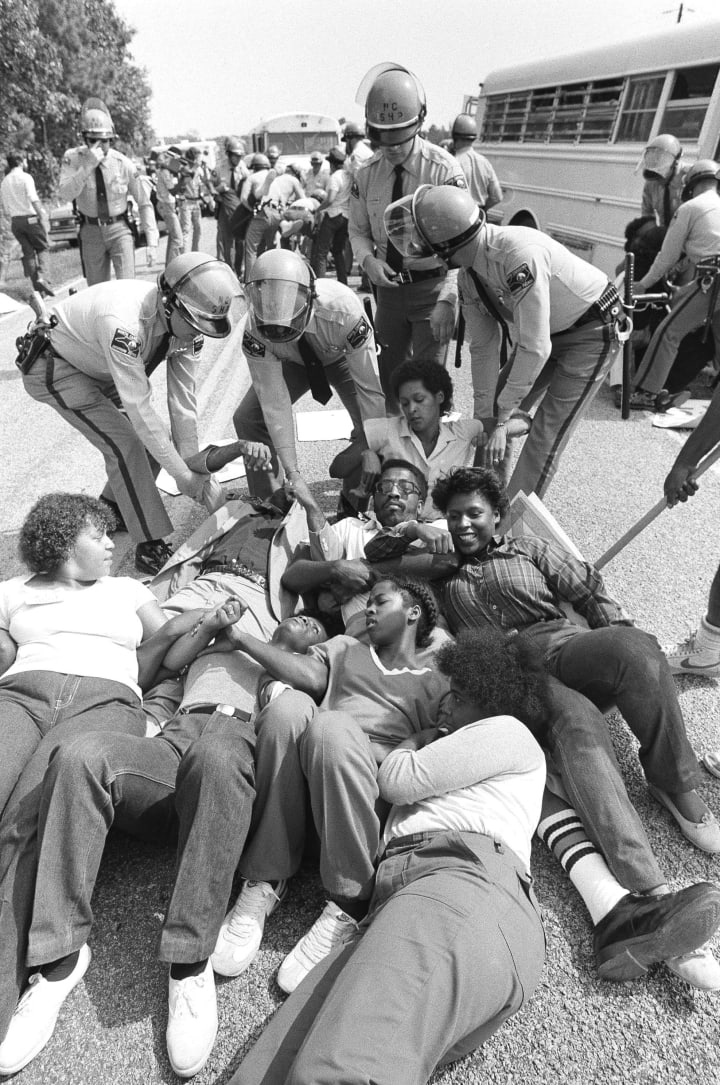

What’s even more alarming is these minority communities are often forgotten about when it comes to environmental improvement. In 1983, the Congressional Black Caucus conducted a study of waste facilities in the South and found that 75 percent of garbage dumps were in Black neighborhoods even though Black people made up less than a quarter of the population. We can still see minority communities being affected today like the residents of Flint, New Orleans, Detroit, and other communities of color that desperately need sustainable action.

Think about the start of the “no straw” campaign as well. There are disabled people that need straws to survive. Their voices were forgotten as masses cried out against straws, many not thinking about the important role plastic straws serve for those who do not have a reusable, metal straw laying around at all times.

This is why intersectional sustainability is so important. It forces the environmental movement to think about everyone who could be affected by climate change and how we can help all to survive.

Currently, the sustainability sector is ruled by the privileged. The ones who can afford to trade in their car for a shiny electric car. The ones who can afford that overpriced jacket that’s been sustainably sourced and made with 100% organic hemp. The ones who can make saving the planet a priority because knowing when your next meal is or having reliable housing will never be a pressing concern.

This type of sustainability is not viable because everyone needs to be able to live green if we want to make real change. Buying that reusable $10 bamboo utensil set will not make humanity more prepared for the devastating effects of climate change if the rest of the world is forgotten about.

So why is it so worrisome those college students couldn’t name one environmental leader of color?

When Greta Thunberg and Al Gore are the faces of modern-day environmental justice, it means people who don’t look like them must fight harder to get noticed.

We can see now how the richer and more notably white spaces get more attention when it comes to environmental technology. They get electric vehicle chargers and the chic organic grocery stores. They receive the incentives of having more green technology because they are the ones who can afford that technology. Without intersectionality in our sustainability, this reality becomes normal. When being sustainable starts to mean being privileged, and the planet is doomed.

To make real change, we need to improve our outreach and education to everyone about sustainability, and this needs to start in our communities. We need participation and leadership from all demographics and walks of life to make meaningful, environmental impact on all parts of the world.

We only have one earth, so let’s make sure we’re all on the same page.

About the Creator

Madelyn Collins

Just writing what comes to mind. | Digital Media Specialist | Dancer | Sustainability Warrior| Founder of Natural Rebels

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.