Facebook’s Australian News Ban a Colossal Blunder

At pains to downplay Facebook’s power and influence, CEO Mark Zuckerberg actually proved both — then lost the battle.

IT CAME SUDDENLY and without warning: on Thursday 18 February 2021, Australians woke up to find news stories gone from Facebook; not just links to Australian news, but news as a category. From anywhere.

Links to news content were blocked to all 13 million users in Australia, as were the local and international Facebook pages of media sites. Users were not only prevented from sharing news content, but any old posts they’d shared, from any news outlet around the world, disappeared.

In true Facebook fashion, the blanket ban also had unintended consequences: hundreds of charities, sports clubs, community groups, arts centres, trade unions and even state and federal government health and emergency services, all who partly rely on the Big Tech behemoth, were blocked. Even Facebook’s own page on Facebook was blank.

The ban was a direct response to the Australian government’s News Media Bargaining Code law, which passed the lower house of parliament the night before the ban, and will come into force once it passes the Australian Senate. Then, just five days later — on Tuesday 23 February — Facebook capitulated after eliciting a face-saving commitment from the Australian government to amend the law at its margins.

But first: How did this all happen so suddenly?

The new law is part of an attempt by Australia to require major digital platforms, like Google and Facebook, to pay Australian news organisations for journalism content shared on their networks. It dates back to 2017, when an inquiry was called into the impact digital platforms on “competition in media and advertising services markets”.

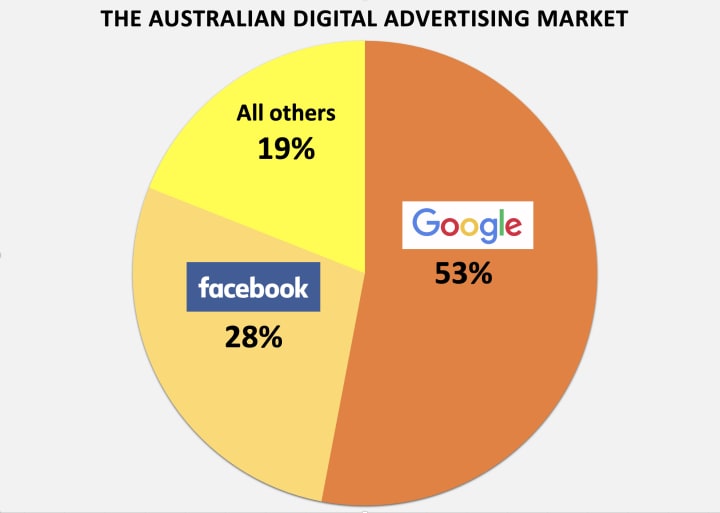

In July 2019 the inquiry, conducted by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), found that for every dollar spent by advertisers in Australia, 53% went to Google, 28% to Facebook and the remaining 19% was shared between all other media companies and websites. And Google and Facebook’s share was growing at an average 12.5% a year as a result of their capacity to tilt the digital advertising market in their favour.

Where digital advertising in Australia was spent in 2019, according to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [Wilson da Silva]

Because Google and Facebook dominate the entry point of Australians to the internet — Google has a monthly Australian audience of 20 million and Facebook 18 million (out of a population of 25 million) — this makes them “unavoidable trading partners” for news publishers, the ACCC said.

The report also found that the output of Australian news and public interest journalism — important for the healthy functioning of a democracy — had been sliding for years, and that the share of advertising revenue going to Australian media outlets was insufficient to fund journalism. Meanwhile, both platforms benefit from the work of journalists, but Australian media outlets receive none of the advertising revenue from such use.

Google and Facebook, for their part, argue that Australian media companies benefit from referrals and click-throughs to their websites provided by the two giants. But Dan Stinton, managing director of news publisher Guardian Australia, said this was an empty claim, since the two dominate what Australians see online.

As he told a January 2021 committee hearing of the Australian Senate, “The internet has become an attention economy, dominated by a small number of very large U.S. tech companies. In fact, Google and Facebook are the internet for most Australians, or at least the key gateway to it.

“Where people go online is largely determined by these two companies’ algorithms, which remain opaque despite their central role in determining what news and information people see,” he added. “The dream of a free and open internet ceased to exist years ago, with just a few huge businesses governing an increasingly centralised web, monetising engagement with content created by the investment of others.”

After consultations with the two tech giants, publishers and public hearings, the ACCC recommended Google and Facebook be required to negotiate with Australian news companies for payment for their journalism content. Where an agreement cannot be reached, the ACCC would step in and act as the final arbitrator, setting mandatory terms.

This was the News Media Bargaining Code, both a new mechanism to fund journalism, a way to address the imbalance in bargaining power between digital platforms and media companies, and a way to address Google and Facebook’s dominant, and conflicted, market position in Australia.

It was this aspect that drove both tech giants ballistic. In September 2020, Google began a campaign to kill the bargaining code, lobbying parliamentarians, displaying dire warnings at the top of every search page seen by Australians, and hiring comedians to attack it in YouTube videos, eventually making a public threat to shut down Google Search in Australia altogether.

In January 2021 Google’s Australian managing director, Mel Silva, told the same Senate committee that the news code was untenable and would set a “dangerous precedent”: “Withdrawing our services from Australia is the last thing that Google want to have happen, especially when there is another way forward.”

That same day, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison shot back: “Let me be clear. Australia makes our rules for things you can do in Australia. That’s done in our parliament. It’s done by our government. And that’s how things work here in Australia and people who want to work with that, in Australia, you’re very welcome. But we don’t respond to threats.”

Reset Australia, a coalition of industry professionals and policymakers seeking to counter digital threats to democracy, said Google was bullying Australia. “When a private corporation tries to use its monopoly power to threaten and bully a sovereign nation, it’s a sure-fire sign that regulation is long overdue,” said executive director Chris Cooper.

Microsoft was quick to offer its Bing search engine to replace Google Search in Australia, promising it would be improved for local users and offer Australians lucrative incentives to advertise. It also said Bing would be happy to comply with the News Media Bargaining Code.

That may have sealed Google’s fate. Within days, Google’s global boss Sundar Pichai was on the phone with the Australian prime minister. By the time the pair held detailed discussions in early February , Google had dialled down its opposition; and on February 15, Google signed its first agreement with a large Australian media company, Seven West Media.

Reportedly worth more than US$30 million a year, the three-year deal will feature the company’s content in a new product called Google News Showcase. Nine Entertainment Co, owner of the influential newspapers The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and The Australian Financial Review, as well as a national television network, was next on February 17, also for a reported US$30 million; the deal gives users access to paywalled content via the Google News Showcase app.

The next day — the same morning Australians awoke to find news blocked across Facebook — Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp announced it had inked a three-year deal with Google that would earn it “significant payments”, and that includes its offshore properties, such as The Wall Street Journal and the London Times, as well as The Australian and Sky News cable television. In the deal, News Corp will also receive ad revenue share from Google.

The sudden move by Facebook — coming so soon after agreements signed by Google — received blanket media coverage across Australia. The country’s oldest newspaper, The Sydney Morning Herald, revealed that Morrison had later that same day spoken with Narendra Modi, his counterpart in India and where Facebook is hoping to expand its WhatsApp service, seeking to support against the tech titan: “PM takes Facebook fight to the world” the newspaper trumpeted.

The move also generated a plethora of negative global coverage for Facebook. London’s Financial Times led with “Facebook bans Australian news as impact of media law is felt globally”, and The New York Times had “Facebook and Google diverge in response to proposed Australian law”.

The Guardian reported that the British government was concerned at the “repercussions of Facebook’s shutdown of large numbers of news and public information resources in Australia” and confirmed that a government minister would be meeting with Facebook later in the week.

When Facebook instituted its ban on February 18, it told media companies it would not do any deals if the Australian government’s News Media Bargaining Code became law. But barely five days later, after telephone calls between Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Australia’s Treasurer Josh Frydenberg, Facebook backed down — accepting the principle of paying Australian publishers for news, and agreeing to arbitration by the government.

Frydenberg, in a television interview on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation two days before Facebook acquiesced, said no amount of pressure from Google or Facebook would make the government abandon the law. “This has been the product of an 18-month inquiry … and at every step of the way, these businesses have been consulted. Now, the goalposts seem to be shifting, because originally they had a concern with the algorithm requirements of notification. Then it was about value exchange, and then it was about a final arbitration model. Now we’re told that if we go ahead with this, we’re going to break the Internet.”

Most commentators believe Zuckerberg had massively overplayed his hand — including Stephen Scheeler, his former chief executive in Australia and New Zealand.

“The standoff between Australia and Facebook could be the catalyst for genuine global reform,” Scheeler wrote in an opinion piece in The Age. “It could be that future historians of the Internet come to see this decision as the moment the world sat up and started to take serious action on making Big Tech accountable to society.”

By taking such aggressive against a middle power, Zuckerberg may have been trying to send a tough message to other countries to back off on regulation, Scheeler argued. But Zuckerberg can’t have it both ways: he can’t downplay Facebook’s power and influence — its unique role in information supply, propaganda and democracy — and then use that very same power against a whole country and pretend it’s just a commercial disagreement.

“Turning off the news, overnight, to millions of people as a bargaining chip in a commercial dispute is a truly shameless demonstration of corporate might,” he added “Cards are now on the table. And this is where it may have overplayed its hand. By using its enormous power intentionally, Facebook may have made it impossible for the world to continue ignoring that it has that power.”

Like this story? Please click the ♥︎ below, or send me a tip. And thanks 😊

About the Creator

Wilson da Silva

Wilson da Silva is a science journalist in Sydney | www.wilsondasilva.com | https://bit.ly/3kIF1SO

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.