Drugs and Street Art vs. the US Government

This is a piece I wrote for my college writing class.

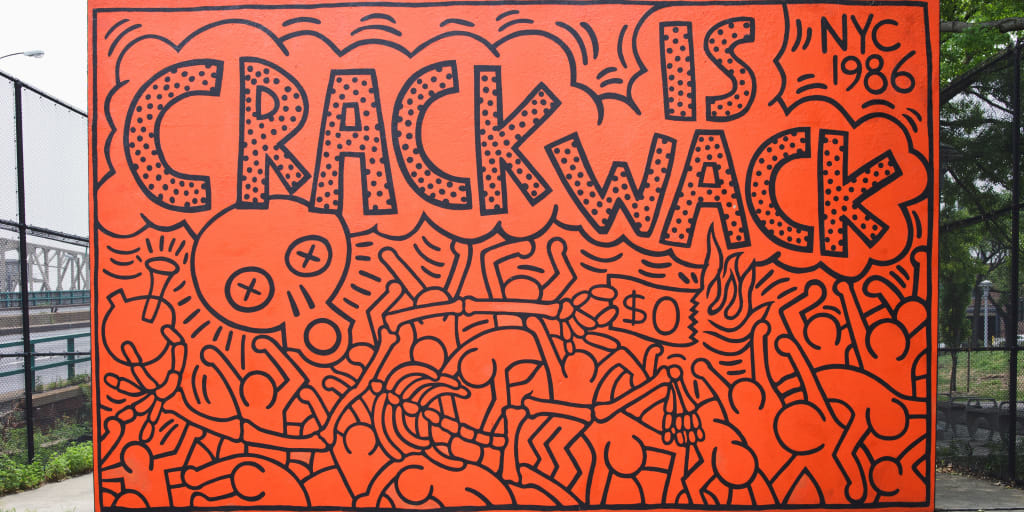

Keith Haring’s “Crack is Wack '' mural stands tall, 35 years after its creation and although Haring has passed away and the crack cocaine epidemic has subsided the mural serves as a lasting reminder of both. Additionally, the mural is an emblem of grassroots activism in its purest form, street art. Keith Haring, born in 1958, is well known for his distinguishable art style characterized by bright colors and a cartoonish depiction of people. Haring began his work in New York subways. With black paper and chalk in hand he would ride from station to station looking for blank spaces in walls or trains that he could draw on. Haring did most of his work during the height of the AIDS epidemic, which he was passionate about due to his own sexual preferences as well as having contracted the disease himself. Unfortunately, AIDS is what took Haring’s life in February of 1990 at the age of 31. He used his talent in order to call attention to the disease, and most importantly put an end to the hurtful stigmas surrounding gay men at the time. Additionally, he used his art to advocate for other large issues such as the crack cocaine epidemic which took many young lives in the United states. The United States media and government were constantly broadcasting wrongful and stigmatized information about AIDS and crack cocaine, thus making these matters of public health taboo. Haring explicitly went against this taboo and created graphic images of sexual reproductive organs and sexual positions when it came to his artwork about AIDS. In an article about the relationship between AIDS and art, Mary Wyric states that “social realities for disenfranchised people are represented in accessible forms that educate and promote political intervention at a grassroots level,” Haring knew this and used it to his advantage in order to bring attention to another large issue, the crack cocaine epidemic (46).

In the 1980s, the United States experienced a large public health crisis when crack cocaine appeared in large cities, however, media coverage and government actions at the time did not reflect the severity of the issue. The crack cocaine epidemic began when the drug became easily accessible due to its mass production in Colombia and cheap nature once it actually reached American cities. The drug quickly ravaged the American metropolis and snowballed into an epidemic. However, the Reagan administration did not view it as such and instead used the drug as a scapegoat to blame other governing issues on, such as the economic crisis and other urban issues. Additionally, the media’s portrayal of the epidemic was influenced by the government and reported on myths about the drug and helped to create the stigma and taboo that surrounded the drug and its users. Most of the people using and selling the drug were of lower classes, and racial minority groups who were already being villainized by the government. An article in the Journal of Psychoactive Drugs by Donna Hartman and Andrew Golub explains that the media’s portrayal was “armed with a sense of moral superiority, this coverage made it easy to dismiss the disadvantages experienced by minority, urban poor as self-inflicted matters of individual choice and self-indulgence as opposed to recognizing them as matters of economic history, social structure and racial inequality” (424). Moreover, the media created and broadcast misconceptions surrounding the drug and its users that were incredibly misleading, sometimes offensive and biased in order to blame lower classes and minorities. Hartman and Golub emphasize that these myths caused widespread panic when really they were reflective of pre-existing social problems. There was a lack of helpful information in the media, most of it was stigmatizing and government campaigns such as the war on drugs, D.A.R.E, and “Just Say No” were only preventative at best. There was essentially nothing in the media that urged individuals to help their addicted friends or family members, or that provided resources for users themselves to seek for help. In fact, Hartman and Golub quote a New York Times article from 1985 stating that the drug was “alarming law-enforcement officials and rehabilitation experts,” this information would be discouraging to any seeking help (429). Needless to say, “the insinuation by journalists and politicians that a particular drug is at the root of the problems facing the minority underclass in our inner cities is an obvious oversimplification” and creates a skewed view of one’s nation.

Haring’s mural helps to break down the hurtful stigma and stereotypes surrounding users of crack cocaine. The mural itself doesn’t portray a specific race or economic class, the figures are all human with zero noticeable distinctions. Additionally, the phrase “Crack Is Wack” speaks to the drug, and not the users, this is different from the media outlet’s insinuations that the users were “wack.” Haring had firsthand experience with the drug when his friend and studio assistant Benny Soto became addicted to crack cocaine, and thus gave him “a very personal reason why [he] wanted to do this particular mural” (Gruen 149). In the same interview Haring goes on to explain that “at that time, people didn’t understand the complexity and danger of the drug” thus, people began smoking crack cocaine and had no idea what would happen and how it would affect them (Gruen 149). Through the mural Haring hoped to present an image to the public that urged to think about the possible consequences of the drug without placing blame on a specific group of people. Moreover, the mural was an effort to show the symptoms that were experienced by crack addicts and urge passersby to consider the fact that there were no efforts for rehabilitation being put in place. Lastly, in an interview with Rolling Stone, Haring said “what’s most repulsive is that I don’t think the powers that be really want to stop the crack problem. For them it’s the perfect thing. It makes people very easy to control. After all, the government is really the one controlling the source.” This shows once again that through his mural Keith hoped to portray a different side of the epidemic than the media was portraying.

In a 2001 article by Koon-Hwee Kan, an art professor at Kent State University, characterized the 1980s as “the Golden Age of graffiti art” and goes on to say that “a huge discrepancy between art in museums and the experience of common people'' in this time period (20). Keith Haring was a key figure in this revolution to make art more accessible, and relatable for the average Joe. Graffiti provides a way for the disadvantaged to share their talents and passions, as well as speak out about their struggles, the art serves as a form of activism. The “Crack is Wack” mural is located on East 128th Street and the Harlem River Drive, this neighborhood is known for its low income population. Haring’s choice to place the mural here was strategic, he brought the piece to where the problem was or at least where the media claimed it to be. Now, at this point in Haring’s career he had moved away from the graffiti and street art scene, he was no longer painting on subways and had moved to the more traditional mediums. Thus, the choice to make this specific piece in the traditional graffiti was clearly intentional and helped to serve his purpose. The irony is obvious, most people including the US government associated crack cocaine addicts with illegal activities such as graffiti, and Haring was using illegal street art to call attention to the issue. A New York Times article from 1986 tells the story of Haring’s appearance in court, after having plead guilty and accepting a $25 fine for having illegally painted the mural. Additionally, the article states that “the mural was shown on television, praised by the Crack Foundation and, apparently won the approval of the neighborhood” thus, showing the people’s push against the government’s wrongful coverage of the epidemic (Howe and Prial). This entire process was broadcast and thus, provided a more positive or at least, less stigma driven view of the issue at hand. Lastly, the article quotes Haring’s statement from after the trial, he said “I’m waiting for the city to provide me with a wall” (Howe and Prial). When the city did in fact provide Haring with options of walls for him to recreate the mural, he opted for the same one he had previously used due to its strategic location. The location of graffiti is just as important as the graffiti itself, in the right locations the art urges certain groups of people to stop and think about topics that affect them. Another example of Haring’s strategic placement and content of graffiti is the work he did on the Berlin wall in the same year that the “Crack is Wack” mural was painted. On the Berlin wall Haring painted interlocking figurines in the German flag’s colors, red, black and yellow. Despite Haring being invited to draw on this 300 foot section of the wall rather than doing it illegally, what he drew was not regulated. According to a virtual exhibit done by Paul M. Farber, when Haring spoke to the press about his work later that day he stated that his art allowed for “an attempt to psychologically destroy the Wall by painting it.” Once again demonstrating the importance of graffiti as a form of activism in its purest form. More recently, there have been a number of murals appearing in cities across the United States as a part of the Black Lives Matter movement. Similar to the AIDS and crack cocaine epidemic, media coverage of this issue has been biased and has stigmatized people of color. In order to combat this, artists took to the streets as a way to protest with their talent and call attention to the wrongful killings of African Americans by white police officers. Graffiti continues to be an incredibly important aspect of activism and society, it provides people with a voice and a way to express their talent with a purpose.

Keith Haring was an activist who used his impressive talent as a way to defy the United States government and the media’s prejudice. Futura 2000 or Leonard McGurr, a famous graffiti artist, stated in an interview that “Keith Haring probably gave the [graffiti] movement its greatest exposure” thus, inspiring activists everywhere (Gruen 74). Similarly, Madonna who was friends with Haring stated that “there’s a lot of irony in Keith’s work…you have these bold colors and those childlike figures and a lot of babies, but if you really look at those works closely, they’re really very powerful and really scary;” his artwork made people think (Gruen 93). Activism in the form of art is different from activism in the form of protests and posts on social media because it’s not temporary. Spray painted phrases or paintings on walls are seen by all kinds of people from every single social class, political belief or economic status. Street art is effective, it urges individuals to truly think about their actions and the lives of others.

Works Consulted

“Crack Is Wack: Keith Haring.” Crack Is Wack | Keith Haring, https://www.haring.com/!/art-work/108.

“Crack Is Wack Playground.” Crack Is Wack Playground Monuments - Crack Is Wack : NYC Parks, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/crack-is-wack-playground/monuments/1801.

Donna M. Hartman & Andrew Golub (1999) The Social Construction of the Crack Epidemic in the Print Media, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 31:4, 423-433, DOI: 10.1080/02791072.1999.10471772

Farber, Paul. “Keith Haring (American, 1958–1990).” The Wall in Our Heads: American Artists and the Berlin Wall, 8 Jan. 2016, https://exhibits.haverford.edu/thewallinourheads/artists/keith-haring-american-1958-1990/.

Gruen, John. Keith Haring: The Authorized Biography. Simon & Schuster, 1992.

Howe, Marvine, and Frank J Prial. “New York Day By Day .” New York Times, 19 Sept. 1986, https://www.nytimes.com/1986/09/19/nyregion/new-york-day-by-day-358386.html?searchResultPosition=3. Accessed 14 Dec. 2021.

Kan, Koon-Hwee. “Adolescents and Graffiti.” Art Education, vol. 54, no. 1, National Art Education Association, 2001, pp. 18–23, https://doi.org/10.2307/3193889.

Rivera, Juan. “Keith Haring's Crack Is Wack Mural - from Illegal to Protected.” Public Delivery, 19 Oct. 2021, https://publicdelivery.org/keith-haring-crack-is-wack/. Accessed 14 Dec. 2021. Sheff, David. “Keith Haring: Just Say Know .” Rolling Stone , 10 Aug. 1989, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/keith-haring-just-say-know-71847/. Accessed 14 Dec. 2021.

Taxy, Sam, et al. Drug Offenders in Federal Prison: Estimates of Characteristics Based on Linked Data. U.S. Department of Justice , Oct. 2015, https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/dofp12.pdf. Accessed 14 Dec. 2021.

Wyrick, Mary. “Collaborative AIDS Art and Activism: Content for Multicultural Art Education.” Visual Arts Research, vol. 19, no. 2, University of Illinois Press, 1993, pp. 44–54, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20715806.

About the Creator

Beca Damico

hi :) my name is beca and im a freshman at nyu! i love writing more than anything. in my opinion writing is the best form of self expression. here i will get to share what i am passionate about, i hope you enjoy.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.