Biology and Technology in the Real World: Fracking

Originally written April 22nd, 2016.

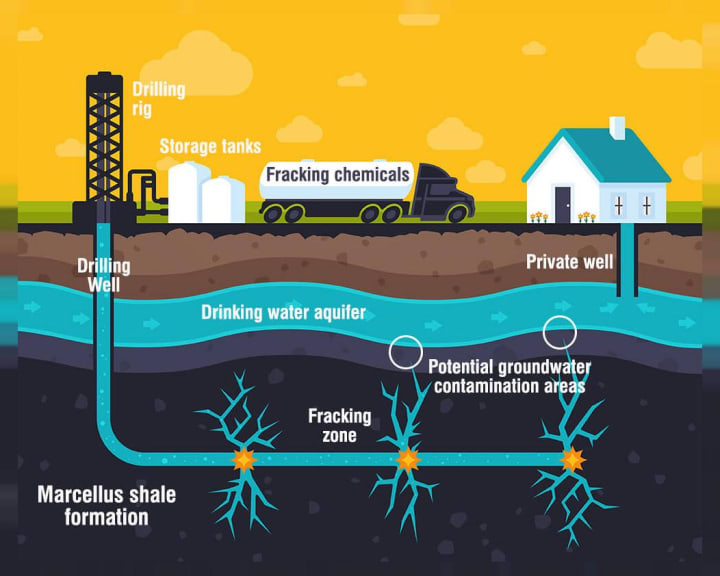

What is fracking? Fracking is the process of drilling down into rock face where oil and natural gas deposits are trapped below. Once a suitable depth has been reached, a mixture of sand, water, thickening agents, and chemicals are pumped into the rock to fracture it. This is why the process is called hydraulic fracturing, or fracking for short. Once the rock has been broken, the solution pumped into the fracture creates fissures in the rock where oil and natural gas deposits can theoretically flow more easily, and they can be siphoned and collected. Fracking was theorized in 1947, with the first successful commercial application happening in 1950. Since then, over two and a half million “frack jobs” have been completed worldwide on oil and gas wells; over a million of those in the US.

Fracking has been championed as a way to maximize the natural gas output from wells, but it is not necessary for the extraction of natural gas itself. Fracking is simply intended to get the most out of these wells, but it is not without consequence. In “Hydraulic Fracturing and Water Management in the Great Lakes”, authors Karisny and Schroeck write: “This technique, used to ‘stimulate’ oil and natural gas wells, allowing for increased production, requires the use of millions of gallons of water and has the potential to cause significant water depletion and aquifer contamination…” (Schroeck & Karisny, 2013).

Proponents of fracking argue that fracking is necessary to improve the rate at which oil companies can extract shale gas, coal seam gas, tight gas, and tight oil. Supporters also argue that fracking the United States’ oil and gas reserves could help us achieve energy independence. Given that the oil industry is extremely large and lucrative, fracking can be seen as an attempt to get the most out of industrial oil and gas drilling. As the number one consumer of oil in the world, the steady flow of oil and gas seems absolutely indispensable to the United States, and ensuring the flow of these resources is treated as vitally as national security in the US.

Interestingly enough, this also has a secondary effect of creating another market for water, not just as a necessary commodity but also as a commercial energy resource, creating a demand not just for millions of gallons of water, but for the rights to that water as well. Authors Margaret Cook and Michael Webber write that: “…some water rights holders sell or lease their water resources to oil and gas producers in an informal water market…the energy sector either directly or indirectly provides the capital for water efficiency improvements in the agricultural sector as a mechanism to increase water availability for other purposes, including oil and gas production…” (Cook & Webber, 2016).

The biggest opponents of the process of fracking argue that fracking uses upwards of 1.2 to 3.5 million gallons of water with each frack job, larger jobs requiring upwards of 5 million gallons. This becomes a problem in water stressed areas such as the state of California, where citizens, environmental groups, and documentary filmmakers such as Josh Fox who directed “Gasland” have argued that fracking is using too much water in a state already starved for it; the idea here being that people will die without water, and that money for the oil companies is not worth this cost. Gasland in particular was such a success as a documentary, that authors Vasi, Walker, Johnson and Tan have noted: “…Gasland contributed not only to greater online searching about fracking, but also to increased social media chatter and heightened mass media coverage. Local screenings of Gasland contributed to anti-fracking mobilizations, which, in turn, affected the passage of local fracking moratoria in the Marcellus Shale states…” (Vasi, Walker, Johnson, & Tan, 2015).

A recent water catastrophe in Flint, Michigan due to fracking has poisoned millions, causing a worldwide media coverage of one of the largest economic and ecological disasters in recent memory. The Great Lakes region is of vital importance not just to the environment, but to the economies of many countries. In “Hydraulic Fracturing and Protection of Freshwater Resources in the Great Lakes State”, author Nicholas Schroeck argues: “…The Great Lakes form the largest freshwater system on the Earth, holding approximately 84 percent of North America’s surface freshwater and 21 percent of the world’s surface freshwater supply. The Great Lakes provide drinking water for forty million people and are essential for the region’s agriculture and manufacturing sectors…” (Schroeck, Hydraulic Fracturing and Protection of Freshwater Resources in the Great Lakes State, 2014).

It is not just the waste of millions of gallons of water that is the problem with fracking. In “Hydraulic Fracturing for Natural Gas: Impact on Health and Environment”, author David Carpenter writes that: “…There are immediate threats to health resulting from air pollution from volatile organic compounds, which contain carcinogens such as benzene and ethyl-benzene, and which have adverse neurologic and respiratory effects. Hydrogen sulfide, a component of natural gas, is a potent neuro- and respiratory toxin…” Towns near the Appalachian Mountains have reported an increase in asthma, COPD and other respiratory illnesses and diseases, and since this area is heavily affected by fracking, it is likely that these noted dangers of fracking are causing these respiratory diseases in the areas around Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and other states.

Carpenter continues, writing that: “…In addition, levels of formaldehyde are elevated around fracking sites due to truck traffic and conversion of methane to formaldehyde by sunlight. There are major concerns about water contamination because the chemicals used can get into both ground and surface water…” The risk of water contamination is legitimate, and in order to see what happens when people try to use tainted water, look no further than the ongoing crisis happening in Flint, Michigan. Using tainted water is causing cancers, tumors, and a whole host of other illnesses, and worse, it is known that the tainted river water in Flint Michigan is due to fracking. Flint’s governor somehow thought that it would be a good idea to save an estimated $5 million by switching the city’s water supply to local water sources, which were tainted by fracking. The cleanup and recovery has already cost upwards of $400 million.

Carpenter continues to write: “…Much of the produced water (up to 40% of what is injected) comes back out of the gas well with significant radioactivity because radium in subsurface rock is relatively water soluble…” This problem in particular is noted to be especially present in places such as Lock Haven, Pennsylvania. My grandfather, Reverend William Lawbaugh briefly ministered to the town, and in the time of a few months living there contracted stomach cancer, which has thankfully since gone into remission after moving away and a few years of treatment.

Carpenter goes on: “…There are significant long-term threats beyond cancer, including exacerbation of climate change due to the release of methane into the atmosphere, and increased earthquake activity due to disruption of subsurface tectonic plates…” Manmade climate change has been extensively proven to exist, and have been made worse by modern industrialized society. Earthquakes are of a particular danger in California, where geologists, environmental scientists and others have noted the high risk of fracking in the state. If tectonic plate disruption caused by fracking were to cause the San Andreas Fault to crack, nearly the entire state of California, almost 40 million people will be swept into the Pacific, shattering the economy in a manner reminiscent of the 2008 crash, and causing the nation to mourn tens of millions of deaths.

Finally, Carpenter concludes with “…While fracking for natural gas has significant economic benefits, and while natural gas is theoretically a better fossil fuel as compared to coal and oil, current fracking practices pose significant adverse health effects to workers and near-by residents. The health of the public should not be compromized simply for the economic benefits to the industry…” (Carpenter, D.; Institute for Health and the Environment, University at Albany, Rensselaer, NY, 2016).

In conclusion, fracking has dangers which far outweigh the benefits. To cease fracking entirely, and clean up all of the damage caused by it, would likely take several decades, if not centuries. But the solution to these problems is not to continue drilling for the propagation of the oil industry. The only way to prevent these problems from happening again is to invest in cleaner energies, creating a market for wind, solar, geothermal and nuclear energies, and prevent the monopolies that allow oil companies to remain in dominance, which will hopefully encourage healthy capitalist competition between green energy companies in a future green energy market. The solution to stopping the damage that gas, oil, and coal are doing to our environment is to radically change the way that the American economy operates. While a daunting task that would take decades of reform, it is not impossible.

References

Carpenter, D.; Institute for Health and the Environment, University at Albany, Rensselaer, NY. (2016). Hydraulic fracturing for natural gas: impact on health and environment. Reviews on Environmental Health, 31(1), 47–51. Retrieved from http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umuc.edu/eds/detail/detail?vid=7&sid=ea5939c3-6e5c-45d6-a7ae-df082bf43df2%40sessionmgr4002&hid=4111&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#AN=114047821&db=ccm

Cook, M., & Webber, M. (2016). Food, Fracking, and Freshwater: The Potential for Markets and Cross-Sectoral Investments to Enable Water Conservation. Water (20734441), 8(2), 1–21. Retrieved from http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umuc.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=16a61eb2-cdf6-4e53-a507-3a17bc2cb00a%40sessionmgr4004&vid=1&hid=4111

Schroeck, N. (2014). Hydraulic Fracturing and Protection of Freshwater Resources in the Great Lakes State. Indiana International & Comparative Law Review, 24(1), 114–132. Retrieved from http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umuc.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=8f96b6d3-e0f5-437f-80cb-9d4060026d97%40sessionmgr103&vid=4&hid=103

Schroeck, N., & Karisny, S. (2013). Hydraulic Fracturing and Water Management in the Great Lakes. Case Western Reserve Law Review, 63(4), 1167–1185. Retrieved from http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umuc.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=2dc15927-47ec-47ad-854e-33019d7e1c15%40sessionmgr120&vid=2&hid=103

Vasi, I., Walker, E., Johnson, J., & Tan, H. (2015). “No Fracking Way!” Documentary Film, Discursive Opportunity, and Local Opposition against Hydraulic Fracturing in the United States, 2010 to 2013. American Sociological Review, 80(5), 934–959. Retrieved from http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umuc.edu/eds/detail/detail?sid=da2db136-af6e-478d-9895-9f3037baf402%40sessionmgr4002&vid=0&hid=4111&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#AN=110479118&db=bth

About the Creator

Johnny Ringo

Disabled, bisexual American socialist and political activist. Student of politics, aspiring journalist, and academic. Bachelor’s of Science in Criminal Justice.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.