Are We Living in a Post-Truth World?

As deepfakes become more difficult to detect, it’s going to get tougher to separate fact from fiction. That has deep implications for how we identify and understand truth.

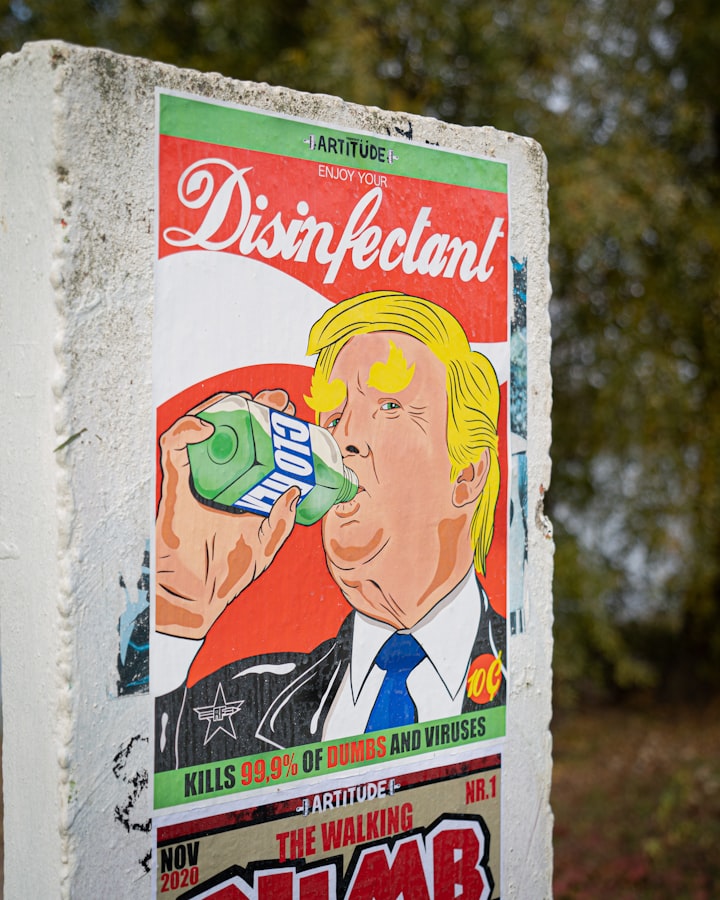

Former US president Donald Trump made 30,573 false or misleading claims during his four-year term. While that’s steep on any scale, the idea that politicians routinely lie to the public is not breaking news. But Trump took his relationship with reality to even shakier ground than usual. He widely dismissed unflattering media reports as fake news. He consistently hurled insults at journalists. And he still claims the 2020 US election was rigged against him.

At the same time, we’ve seen a significant increase in misinformation circulating on social media. According to the Pew Research Center, about 18 percent of American adults say social media is their primary source of political and election news. That’s more than radio (8 percent) and network TV (13 percent).

The same study also found that Americans who use social media as their primary news source are more likely to be misinformed about current events. Only 43 percent of social media users were able to correctly answer questions about current events. That’s lower than network TV (56 percent), print (60 percent) and radio (61 percent) audiences.

This paints a concerning picture of the state of truth in politics and the media. Lying politicians and social media propaganda are contributing to a misinformed populace that is more likely to buy into conspiracy theories, falsehoods and downright lies.

But that might only be the tip of the post-truth iceberg. The emergence of deepfakes is making it even more difficult to distinguish what’s real from what’s not.

Listen to this article on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

What is a deepfake?

During the Russian invasion of Ukraine, a video was broadcast live on a Ukrainian TV network. Amidst on-going resistance from Ukrainian forces, the video footage appeared to show Ukrainian President Volodymr Zelensky calling on his troops to lay down their weapons and surrender to Russia.

Except the video wasn’t real. It was a deepfake. Hackers broke into the TV network’s feed to broadcast it as live news. They also uploaded it to the network’s website. And the video spread like wildfire on social media. Experts quickly debunked the video as a fake, and President Zelensky called it a “childish provocation”. However, the threat of deepfakes to global security should not be so easily dismissed.

In 2018, US comedian Jordan Peele teamed up with BuzzFeed to create a comic deepfake of former President Barack Obama calling then President Donald Trump “a total and complete dipshit.”

While Peele’s video was clearly distributed as a deepfake, it alerted many people to the dangers of this new ability to manipulate video footage and convincingly put fake words into the mouths of world leaders.

Deepfakes are also being widely used in the world of porn. There are entire websites dedicated to celebrity deepfakes that depict your favourite movie stars engaging in hardcore sex acts.

While fake potty-mouthed Obama and fabricated celebrity humping might not constitute an immediate threat to global security, the potential consequences of this kind of deep fakery are serious. From sparking global conflicts to blackmailing just about anyone, deepfakes may fundamentally change how we separate fact from fiction.

So what exactly is a deepfake? At the most basic level, a deepfake is a video- or photo-based face swap — but it’s much more sophisticated than simply Photoshopping one face over another.

Deepfakes use artificial intelligence (AI) to learn from source data about the faked video’s subject. Let’s use Jordan Peele’s Obama deepfake as an example. First, Peele was filmed presenting the speech as himself. Then, real video footage of President Obama was fed into deepfake software for analysis. The AI-driven software learned from the real footage of Obama, then merged the former President with Jordan Peele’s video to create the deepfake.

This is called deep learning, and it creates a much more authentic fakery than older techniques. It makes today’s deepfakes more difficult to detect than cruder versions of the technology that we’ve seen emerge in the past. And with a range of deepfake apps and websites currently doing the rounds, just about anyone can create a deepfaked video with no technical skills required. In fact, you may have already created a deepfake without even knowing it.

FaceApp went viral in 2019. The concept is pretty simple. Users upload their photo to the app, which uses a deepfake AI filter to create an image of the user as an elderly person. It seemed harmless enough, until news emerged that FaceApp was developed in Russia by a company called Wireless Lab. That led the FBI in the US to warn that FaceApp may pose a counterintelligence threat.

At the time, the Washington Post also raised serious privacy concerns:

“FaceApp’s terms of service grant the company a “perpetual, irrevocable, nonexclusive, royalty-free (and) worldwide” license to use people’s photos, names and likenesses — a wide-open allowance that some worried could erode people’s data privacy or control.”

Fast forward to the present day, and FaceApp now owns access to more than 150 million people’s faces and names around the world. While there is no evidence that Wireless Lab is passing its users data to the Russian government, the issue nonetheless takes on new significance as Russia continues to mount the largest attack on a European state since World War II.

Want more interesting content in your inbox? Subscribe to THE MALCONTENT for free.

How are deepfakes being used?

The porn industry is perhaps the most enthusiastic user of deepfake technology. In 2019, research company Deeptrace found that 96 percent of the almost 15,000 deepfake videos its researchers found online were pornographic in nature. The vast majority of those had used deepfake technology to map the faces of female celebrities onto adult entertainers.

However, deepfakes are increasingly crawling out of the murky depths of porn sites. Many remain playful in nature. The Dali Museum in Florida, for example, used deepfake technology to bring Salavador Dali back to digital life as a tour guide. Game of Thrones fans may be aware of the Jon Snow deepfake that depicted the popular character apologising for the somewhat underwhelming final season of the hit show.

Other deepfakes are demonstrating the more concerning side of the technology. Korean television network MBN, for example, raised concerns about the use of deepfakes in journalism when it prestened viewers with a deepfaked news anchor as part of a news broadcast. Putting words into the mouths of respected journalists will inevitably erode media trust in an era when fake news claims are already causing widespread confusion over the validity of news sources.

Scammers recently hacked the Instagram account of two-time world champion surfer Tom Caroll. They posted a deepfaked video that depicted Carroll falsely endorsing their cryptocurrency scam. Perhaps even more concerning is the 2018 effort by a Belgium political party that released a deepfaked video of Donald Trump admonishing the country for signing up to the Paris climate agreement.

So who is making all these deepfakes? Anyone and everyone. New deepfake software has removed much of the complicated technical know-how from the process. There are even online companies that will make deepfakes for you – for as little as $15. You simply upload your source and target videos, and they do the rest. And a range of apps (similar to FaceApp) enable users to make deepfakes with a smartphone and next to no technical knowledge.

One such app is China-based Zao. It invites users to swap their faces with famous actors in popular films and TV shows. But privacy concerns quickly surfaced when the South China Morning Post revealed a clause in the app’s terms and conditions that allows the app’s developer to retain users’ images and sell them to third parties.

Here’s why that’s important. The global facial recognition market is forecast to be worth $8.5 billion by 2025, driven largely by the surveillance industry. The companies developing facial recognition technologies need images to train their algorithms – images like the selfies you may have uploaded to various deepfake or other image manipulation apps.

While facial recognition surveillance may have some positive application in law enforcement, it’s dangerous territory. China, for example, is already using facial recognition as part of the country’s plans to establish a social credit system. The idea is that good behaviour (like paying bills on time) is rewarded and bad behaviour (like jaywalking) is punished under a social scorecard system.

According to the Chinese government, the goal of the system is to “allow the trustworthy to roam everywhere under heaven, while making it hard for the discredited to take a single step.”

Underlying China’s social scorecard system is a vast network of data and technology that uses various means – including facial recognition – to identify and track citizens and assess their behaviours across everything from where they park their bike to how they manage their finances.

The emergence of deepfakes simultaneously throws a blanket over truth as faked videos challenge whether we can believe what we see, and powers the rise of new surveillance states that can use our own images to track and control our behaviour with Orwellian zeal.

Listen to this article on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Can we still detect deepfakes?

Yes — and no.

The FBI says deepfaked videos have a few key tells. Too much space between the subject’s eyes, visual distortions around the pupils and earlobes, poorly timed face and lip movement, and blurry backgrounds are all giveaways. Other sources note a lack of blinking and incorrectly angled shadows can reveal deepfakery at play.

However, rapidly advancing deepfake technology may soon completely eliminate these deficiencies. It comes down to the nature of machine learning. Most deepfake software uses a generative adversarial network (GAN). This essentially gives AI the seemingly magical ability to learn on its own — and get better over time.

GAN identifies patterns in input data. It then uses these patterns to train the AI in how to generate new examples of the input data.

For example, in the wild world of deepfakes, the input data is the real footage of the person — or subject — you’re faking. This footage is what will teach the software how to create a fake of your subject. The more input data you feed into the system — or the more footage of the subject you feed the AI — the better the quality of the deepfake.

But it gets a little more complex than that. The part of the process that generates the new faked video is called the generator model. As the generator model is creating new faked video footage, a discriminator model kicks into gear. Its job is to identify the footage coming out of the generator model as fake or real. This trains the generator model to learn what’s fooling the discriminator model.

So the discriminator model is kind of like a built-in detective that coaches the generator model. With every fakery the discriminator model detects, the generator model is learning to become a more polished forger.

As this internal battle between the generator model and the discriminator model becomes more advanced, the quality of the deepfaked videos it is capable of producing will increase. Some experts have said that perfect deepfakes that are indistinguishable from the real thing may only be six to 12 months away.

But that doesn’t mean the forces for truth are laying down without a fight. In 2019, a group of leading tech companies — including Microsoft and Meta (formerly Facebook) — teamed up to create the Deepfake Detection Challenge (DFDC). The idea was to bring experts together from around the world to create new deepfake detection technologies. More than 2,000 experts from around the world submitted 35,000 deepfake detection models, and Meta is currently working with the winners to help them release open-source code for the top-performing detection models. This should encourage open, worldwide collaboration among deepfake detection experts, and help them to develop new detection models that keep pace with advances in deepfake technologies.

Want more interesting content in your inbox? Subscribe to THE MALCONTENT for free.

Food for thought

We’re currently in the very early stages of deepfake technology. As deepfaking techniques rapidly improve in the short-term future, we’ll likely begin to see a proliferation of high-quality deepfake videos that are virtually impossible for non-experts to detect. While the hope is that deepfake detection technology will advance at the same pace — or faster — than deepfaking techniques, this is by no means a guarantee.

So it’s possible that, within a handful of years, we’ll be living in a society awash with deepfake videos that are very difficult to detect. If that means we can no longer believe what we see in video footage, it’s possible that we’ll fall deeper into the post-truth era.

Politicians will be able to create and disseminate fake but convincing scandals to destroy the credibility of their opponents. Sensationalist media outlets and ultra-conservative influencers will be able to spread increasingly persuasive — and damaging — conspiracy theories. Scammers and blackmailers will have a powerful new tool in their hands. And nefarious players could spark global conflicts with faked footage of world leaders making inflammatory claims.

This is essentially the emergence of a powerful new take on 21st-century propaganda. The strategic use of disinformation has historically been used to control populations, start and prolong major conflicts and world wars, and build support for fascism.

In the Trump-era, we saw how the agenda-driven rejection of fact can be used to create deep divisions in a society. Half truths, distorted contexts and deliberately misinterpreted statistics were weaponised to undermine fact-based debate. When we allow misinformation to transform public discourse into a vacuous mud-slinging match between left and right, democracy is reduced to a he-said, she-said race to the bottom. Adding deepfakes to that dumpster fire could be the end of truth as we know it.

Shane Conroy is a freelance writer and the founding editor of THE MALCONTENT. Subscribe for free at THE MALCONTENT.

About the Creator

Shane Peter Conroy

Shane is just another human. He writes, he paints, he reads. He once got his tongue stuck to the inside of a freezer. Actually, he did it twice because he thought the first time might have been a fluke. https://themalcontent.substack.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.