Love, Haight, and Tie Dye

A lasting legacy from the ‘60s

“The heepies lived here.” My Russian landlord paused to make sure I understood.

“What? Oh, the hippies.”

“Yes, the heepies. Crazy colors on everything when we bought this. Psychedelic. My brothers and my father and I had to paint it all.”

The Russians had done a good job of returning the San Francisco Victorian to its original elegance. Three-stories high, the Haight Street apartment building opened to views of Buena Vista Park on the north. The views from the south, where my dining room bay window was, looked out over the city, Golden Gate Park, and on toward the Golden Gate Bridge. Fog horns sounded, a comfort during the night.

My landlord’s twin brother also lived on the top floor with a high school buddy. Another brother lived on the second floor with his wife, a histologist. Born in China, the family fled to Brazil where they picked up a love of samba before joining San Francisco’s robust Russian community. Hard workers, managing the apartment building was their second job. We became good friends.

It was 1978 when I moved to Haight Street, just over a decade after the Summer of Love flooded the neighborhood with young people. The suburban kids in ethnic and Native American-influenced hippie outfits had moved on or morphed into the panhandlers now lurking in front of the hand laundry and the Free Clinic. My apartment mate, Charlie, and I dressed down when we went out into the Haight in an attempt to minimize their pestering. We were both interns at a nearby hospital and had little time for street talk about the ashram, Zen, the zodiac, and such. Charlie kept an Army surplus jacket to wear as street camouflage. I lacked a regular disguise.

One morning I decided to shop after a night on call rather than go straight to bed. I figured I looked disreputable enough to dodge the beggars. Still in my scrubs, my hair unwashed, my gaze blurry, I walked several blocks to the grocery. I put my few items on the conveyor belt and the clerk totted them up. I filled out the Wells Fargo check, the checks I had — for the first and last time — emblazoned with an “M.D.” after my name. The clerk looked at the check, looked me over, looked back at the check.

“You certainly keep a low profile, don’t you?”

Besides the panhandlers, one of the remnants from the Haight Street of the 1960s is the classic hippie tie dye. I had rubbed elbows with the tie dye craze before I moved to San Francisco.

In the early 1970s, I lived in another top floor apartment, in Montreal while I studied at McGill. My fourth-floor walk-up was in a brick blocky structure built as tenement housing in the 1920s. This was my first experience living in a metropolis and there was much I did not understand. Everything I knew about tenements came from Bettie Boop cartoons and other such sources of wisdom. At first, I thought I lived in a slum as the garbage can was on the fire escape and I had a rope clothes line connecting my apartment with the next housing block. I confused taxi cabs with police cars. (In Ohio we only had a sheriff and — if we were lucky — saw little of him.) The apartment was in the Snowdon neighborhood, home of Montreal’s oldest synagogue and a predominantly Orthodox Jewish area. Clusters of bearded Hasidic men would stride down the sidewalk, high-crowned black hats on their heads, long black rekel coats billowing. Their little sons ran ahead of them, earlocks waving. Shops were closed on Friday for the Sabbath and open on Sundays.

Two elderly sisters lived in the apartment next to mine. I saw them about once a year, but daily I heard their tea kettle whistle and the floor boards squeak as they walked up the hallway to turn it off. Across the hall, two women lived in one apartment and four young men in the other. Artisans, the men made their living selling handcrafted items on the streets of Montreal. Billy blasted copper with a self-customized blow torch to “flame paint” rainbow colors on jewelry and décor. His work was inventive. Billy was juried into the Smithsonian’s craft exhibit and was commissioned to create a decorative wall for a Canadian bank. Mel did silverwork.

The other two, Jason and Mark, created tie dye art. They bought bolts of velvet in the garment district, tie dyed it with bleach, and framed the results as large art works. Tourists, everyday Montrealers, and business owners snapped it up. Amazingly, the pair pulled in $20,000 (Canadian) a year — the equivalent of $99,783.65 in today’s US dollars. The money was more than enough to keep them in their favorite food — bagels from the shop across the street, smeared with raspberry jam.

The two weren’t the only ones making money in the early ’70s from what began as a humble fabric treatment.

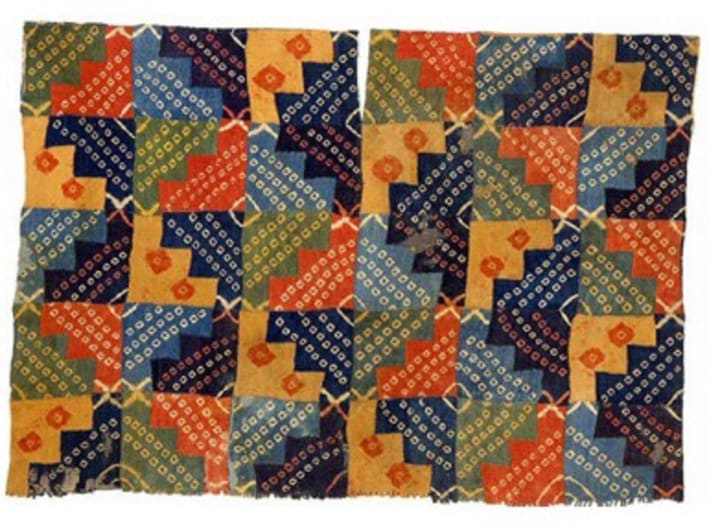

Tie dyeing depends on a resist — something is done temporarily to make specific areas of a fabric resistant to dye. For thousands of years all across the globe fabric dyers have figured out ways to use this idea to make patterns on finished cloth. Wax serves as the resist in Indonesian batik. The wax coats portion of the fabric, which is then dyed and finally, the wax is removed. Japanese shimbori, often done with the natural blue dye indigo, uses several techniques as resists. Fabric might be folded, bunched, put under blocks, twisted, tied, or sewn before the dye is applied. West African tie dye technique uses string or small strips of grass to bind cloth before it is dyed. Pre-Columbian Peruvians tie dyed complex patterns as early as 500 A.D.

Americans knew about tie dye technique for decades before the Summer of Love. A Columbia professor demonstrated it in 1909. In the 1920s, tie dying technique was taught as a craft to school children. But with the rise of hippies in the 1960s, tie dyeing became a permanent force in fashion.

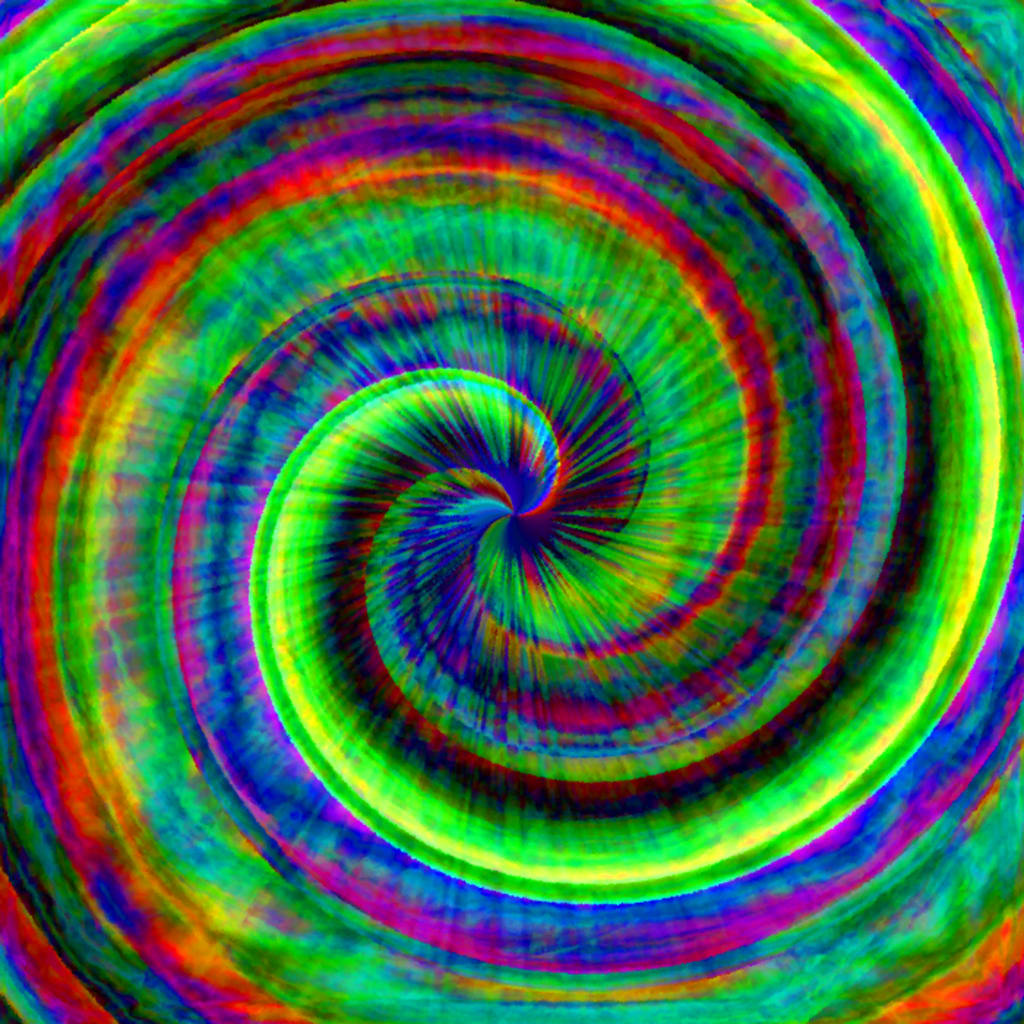

Many credit Ann Thomas, “Tie-Dye Annie,” an artist in the Haight Ashbury district for setting off the craze in the 1960s. Tie dyeing is an inexpensive, easily learned way to bring the so-called psychedelic look to fabric and clothes (including used, old, or vintage finds). Tie dyeing fit right in with the era’s love affair with hand crafts.

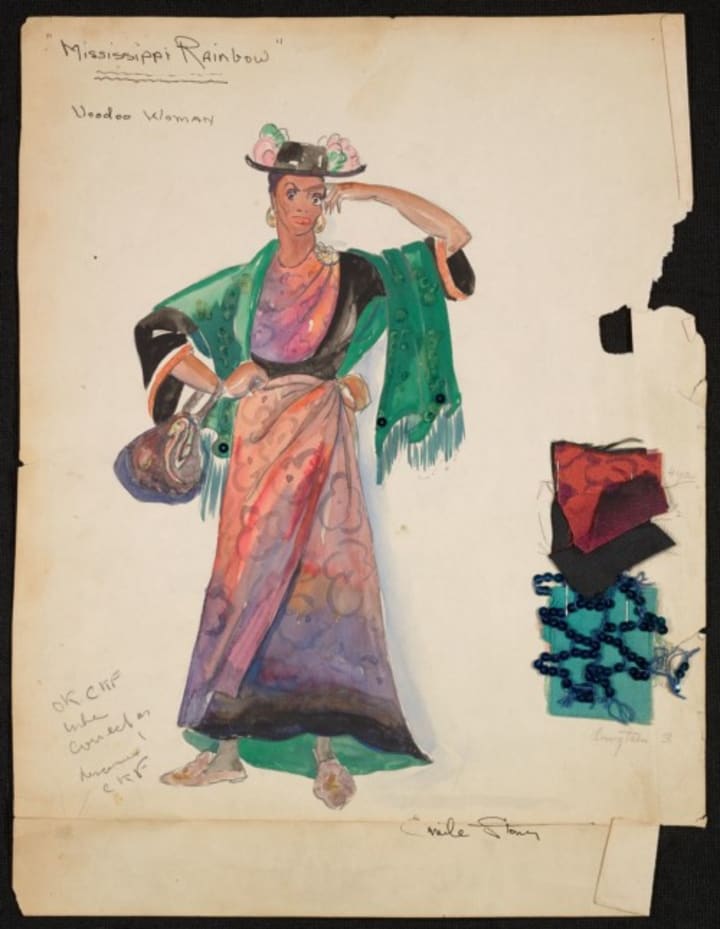

Around this same time, RIT, an American company which manufactured dye for home use, saw a decline in demand. RIT hired marketer Don Price who worked with “some creative types” in Greenwich Village. They recommended development of a liquid dye which would be more easily used than the prior powder. Don Price funded artists to make several hundred tie dyed tee shirts to sell at the Woodstock festival. He also challenged the artist couple Will and Eileen Richardson to come up with new uses for RIT dye. The Richardsons taught themselves tie dyeing in four days, then went on to found the Up Tied textile house. Up Tied promoted tie-dyed luxury fabrics such as silk and chiffon and really took off with a $5000 order from designer Halston. By 1970 model Marisa Berenson was posing in a tie-dyed silk caftan by Halston in Vogue magazine and the Richardsons won a Coty award. So, while the hippies and Rock and Roll stars out in California were tie dyeing thrift shop jeans, East Coast fashion mavens were sporting tie dyed fur, silk, and velvet.

Tie dying never went away. It is tightly tied to memories of Janis Joplin, Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead, and Woodstock. John Sebastian, taught by Tie-Dye Annie, tie dyed all his own clothing. His tie-dyed cape is enshrined at Cleveland’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Vogue regularly showcases tie dyed clothing in its publications. Paparazzi photograph celebrities from Kanye West to Felicity Huggins in tie dyed outfits.

For those yearning to relive the 1970s, the current Netflix miniseries Halston includes one of his now-vintage tie-dyed silk caftans.

Few crafts give as much bang for the buck, please as wide an age range, and offer the flexibility of tie-dyeing cloth. If you’d like to have a try, you can find kits of dye online or in craft and hobby shops. Add a low-cost three-pack of cotton undershirts and you’re all set. Or go even lower cost and use bleach on an old pair of jeans or other piece of clothing. With tie dyeing, whatever you do, you can’t go wrong.

About the Creator

Diane Helentjaris

Diane Helentjaris uncovers the overlooked. Her latest book Diaspora is a poetry chapbook of the aftermath of immigration. www.dianehelentjaris.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.