In Praise of Embroidery

Never underestimate the power of a needle

A long time ago, 1860 to be exact, a young Swiss man Arnold Zuppinger sailed to Manhattan to sell his father’s goods. Arnold was the son of a wealthy Zurich textile manufacturer who owned a silk mill in the French Alps. Zuppinger’s raw and woven high quality silk would win international recognition for excellence in 1862.

The Zuppinger family had originated as farmers in the canton of St. Gall, east of Zurich. There, the unpaved “Zuppinger Road” on the outskirts of town still leads past an impossibly neat barn and farmhouse. Glossy brown cows graze in meadows. Cylindrical haybales, each one pristine in its own turquoise fitted cover, follow the line of electric fencing.

St. Gall’s love affair with embroidery has deep roots. Farm families, embroidering over the fallow months of winter, could bring in a little extra cash. By the 1700s, as many as 100,000 people were busily decorating cloth with thread. Over the next century, St. Gall blossomed into the world’s largest embroidery exporter and became a center of excellence for the art.

With industrialization, canny farmers set up embroidery machines in their dank cellars. Child labor laws were skirted as, out of sight, boys and girls produced embroidery. One boy vented his grumbles in his diary. After dinner, he’d be sent to the basement to operate the embroidery machine until ten or eleven at night, only to be awakened at four the next morning to put in a few more hours before school. An embroidery agent crowed no factory floor boss was as tough on their workers as these farm parents were.

St. Gall still carries cachet, but now the work is done by adults. St. Gall embroidery enlivened Michelle Obama’s yellow coat and dress at her husband’s 2009 Presidential Inauguration and can be found in other high-end fashion creations.

Arnold Zuppinger would cross the Atlantic a total of seven times, hawking his father’s wares, before settling in the US. Threads of his influence can still be traced across his descendant’s lives.

The Zuppinger family in Switzerland maintained their silk mill until the 1930s. Then, its sale helped his granddaughter (my grandmother) and her family survive the Depression. His great-granddaughters — my mother and her three sisters — discussed textiles with sophistication, always using French fashion terms. Gabardine, serge, corduroy, voile, batiste rolled off their tongues.

By age four, I knew what plisse was and why it was the best fabric for my summer nightie. My mother and aunts favored textiles as presents to each other. Bedclothes, bath towels, kitchen towels, and handkerchiefs often appeared gift wrapped with a bow. When I wanted to please my mother with a floral print or design, I would just pick the one that looked most like it came from Heidi’s Swiss meadow.

I cannot count my day complete

’Til needle, thread and fabric meet.

~Author Unknown

My grandmother embroidered until the day she died; my mother, as well. Even my grandfather, sick in bed as a child with measles or some such rashy illness, embroidered a picture of a wagon train which we still own.

Before I went to kindergarten, my mother gave me my first piece to embroider and taught me how to embellish it. A cushion top with a big scarlet-orange poppy printed on it, I still see it clearly. I sat in the sun in the back of our home in Dayton. Remembering the sunlight, I must have been at our dining table by the window. Which makes sense as then I was within a few feet of my mother as she did her work in the cinnamon-scented kitchen.

My mother trusted me with the needle and showed me how to outline the flowers with cotton floss. Nothing was beyond me in the world of embroidery. Always patient and logical, she showed me how to wrap the floss the correct number of times around the needle. I pulled the back end of the yellow cotton taut with one hand as I plunged the point through the fabric with the other. And there it was — a perfect French knot, one of several making the poppy’s stamens.

From the manner in which a woman draws her thread at every stitch of her needlework, any other woman can surmise her thoughts. ~Honore de Balzac

As I grew older, embroidery continued. At sixteen, I spent my allowance savings on a Scandinavian linen sofa pillow kit for my grandmother. The flower’s colors were acidy — yellow, green, chartreuse. It was the only piece of real linen I saw until adulthood. Cotton was more in line with my family’s budget.

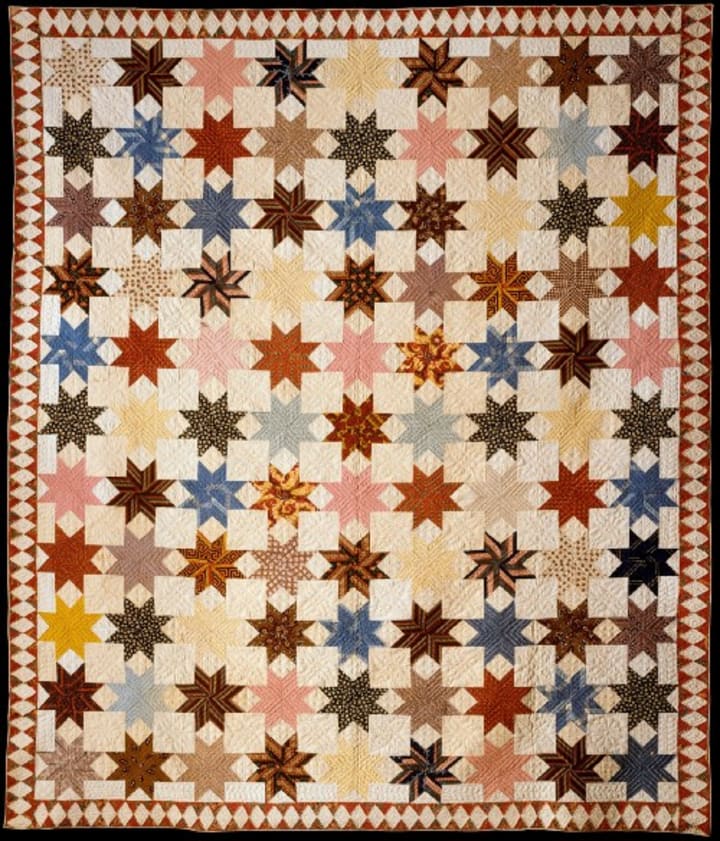

My dad’s mother also worked in fabric. From eastern Kentucky, her wedding gift to my parents was a pair of handmade cotton quilts. They had a star motif. I researched the pattern and found it to be a French star, the LeMoyne. Grandma’s ancestors included a French Huguenot named Amer Via (or, “DeViar”) who immigrated to Virginia in the 1680s. The possibility of a French design continuing on hundreds of years later is intriguing, but for all I know she got the pattern from Sears. Grandma’s gifts to me, that I recall, were a shell necklace and a set of table scarves stamped for embroidery.

The eye that directs a needle in the delicate meshes of embroidery will equally well bisect a star with the spiderweb of a micrometer. Maria Mitchell

As medical school came to an end, the surgeons pushed to have me join them. I had worked for the school’s head of surgery for two years and done well. I loved it loved it loved it. As you might imagine, a woman who’d been wielding an embroidery needle for over twenty-two years did very well compared with the male med students who were picking up a needle for the first time.

All my scattering moments are taken up with my needle. Ellen Birdseye Wheaton, 1851

As a physician, I applied the same neatness, care, and skill that I had used to make my grandmother’s cushion top as a teen.

I remember a roughneck mother who brought in a child with a facial injury. I recommended we ask a plastic surgeon to come in to fix the little boy and give him the optimum end result.

She said, “No, you go ahead and do it. Everyone in our family has scars.”

Her lack of empathy broke my heart. I made sure I used the thinnest suture possible, and sewed tiny, evenly-spaced, stitches with my one-centimeter-long curved needle. I was grateful my laceration repairs typically healed well and looked good, thanks to decades of embroidery practice.

When I visited my family in Greece, my relatives’ fabric work resonated with me. My cousin’s wife, Demetra, impressed me with her ability to embroider with real gold. I had never dreamed of sewing with gold. I left Greece with samples of her fine embroidery.

As far as we could tell, the face of the revolution was a sea of embroidering women, patiently waiting the resignation of their repressive governor. Diana Denham

Embroidery is mostly women’s work.

Like other fabric arts, women have used it in many ways — some of them downright political and even subversive. Right now, I follow artist Diana Weymar. Her project features (mostly) women’s embroidery of verbatim quotes from President Trump’s Tweets, stitched onto vintage textiles. For example, a 1950s handkerchief decorated with a man in a sombrero might have a quote about immigration. I enjoy the snarkiness.

Memories are stitched with love. ~Author Unknown

A few years ago, I designed an embroidered lavender sachet. I researched the plant and figured out a simple design to depict it. I then embroidered linen sachet bags with this design and sold them. I also supplied a local woman who owned a lavender farm. She’s become a friend and we joke about how much money we don’t make.

Of course, just when her lavender fields were decimated by repeated rains and I toyed with the idea of stopping this nonsense, she shared an email she’d received, commenting

“I guess we have to keep doing this.”

In the email, a woman poignantly described looking in vain for my friend’s booth at a craft fair. Years before she had purchased one of the lavender sachets I made and my friend sold. The woman had given it to her aunt. She enclosed a photo of the sachet in her email. Her aunt had loved this sachet. When her aunt died, a number of her children and grandchildren asked about the sachet. They had hoped to lay it atop her ashes, but the woman had left it at home. She was writing my friend to ask for more sachets to give as remembrances to her family members.

As my friend wrote,

“Diane,…we didn’t know that our work could mean so much!”

Take your needle, my child, and work at your pattern; it will come out a rose by and by. Life is like that — one stitch at a time taken patiently and the pattern will come out all right like the embroidery. Oliver Wendell Holmes

About the Creator

Diane Helentjaris

Diane Helentjaris uncovers the overlooked. Her latest book Diaspora is a poetry chapbook of the aftermath of immigration. www.dianehelentjaris.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.