From the Eyes of the Mambabatok's Apprentice

A journey to learning about our pre-colonial past through hand tapped tattooing.

I come from a bougie ass family that owns a resort in the Philippines where I needed to mind my p’s and q’s and constantly be a proper lady. In my private secret thoughts, my escape from placating the hollow, self-important people of our family business was getting tattoos. In the modern Philippines, tattoos are still not viewed in a positive light. One drunken night, I got my first tattoo in West Palm Beach with my friends where I had to forge my mother’s signature to get it done. It was a discreet, hideable tattoo on my lower back. Of course, it didn’t stop there, I acquired more hideable tattoos, but after more than two years of hiding my tattoos from my mother, my sister outed me, and my angry mother responded with, “Tattoos are for pirates, prisoners, and whores!” Of course, my snarky side got the best of me, “What if I wanted to be a pirate prisoner whore?” I can still remember vividly the sting of that slap across my contemptuous mouth. My rebellion had been satisfied, but there was still a yearning for something deeper. For years I languished in a superficial understanding of the markings of pirates, prisoners, and whores.

In the summer of 2016, I had the good fortune to meet Lane Wilcken, a Filipino-American practitioner of the ancient tattooing arts of the Philippines give a lecture in New York City about Philippine tattoos. In his 30-minute talk, I felt like my brain, my heart, and my soul were reawakened to ancestral knowledge in such a short amount of time. My mind was blown upon learning about our rich pre-colonial cultural traditions and that ritual tattooing is not exclusive to the people of the Northern Philippines, as many Filipinos tend to believe, but was found in most ethnolinguistic groups across the archipelago. I learned that these sacred marks were mnemonic devices for oral history and our ancestors’ journeys. Most importantly, our people anciently believed that our markings were a way for our ancestors to recognize us in the underworld. Looking back at our first meeting, I am sure that my ancestors led me to Manong Lane and this information.

On October 4, 2016, After producing a 4-day Filipino-American event with merely 20 mins of sleep each day, I got my first culturally appropriate markings. We stood facing West on my balcony, as Manong Lane chanted to summon our ancestors to join us in ritual, requesting that they bless and recognize the tattoos about to be given. As we settled on mats on the floor of my small cramped room in Chicago, we silently prayed for further protection and guidance. After that profound moment of silence, the rhythmic tapping of the bone tools began, and I felt a slight pinch on my skin. The tapping sound felt simultaneously familiar and strangely soothing. Then it dawned on me that I may be the first one in my family for generations to have these markings done in this way. The feeling was both visceral and empowering. When the piece around my wrist was complete, I felt like I had unlocked a new level in this game of life, or how Hagrid told Harry Potter that he was a wizard. It felt very other-worldly. Manong Lane patiently explained the significance of my marks, the meanings of their placements on my body, and the myths and beliefs that accompany each symbol. After all, it wasn’t just a bunch of triangles and zigzags on my skin; it was my fast pass to the underworld/afterlife. My tattoo told the story of where I came from, my role in the community, and depicted my ancestors in their animal form, the crocodile. It was radically different from all the tattoos that I had received before and in that sacred moment what I was searching for in tattoos came into reality. Since that day, I have received mostly ancestral markings, and every time I have been marked, it reveals more of my people’s story on my skin.

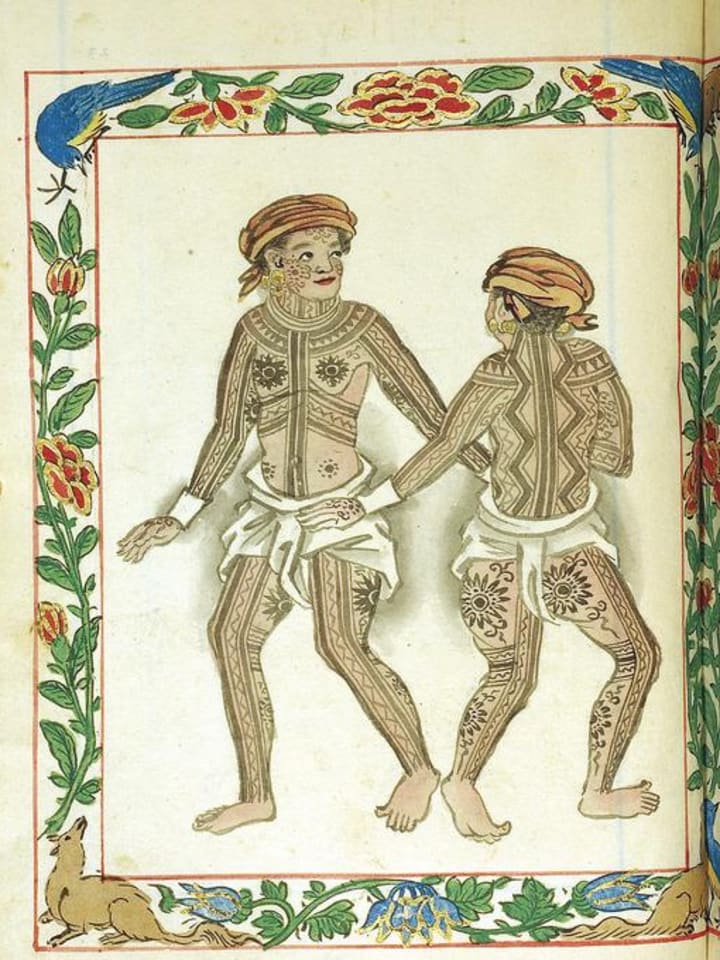

Through Manong Lane I learned that the Philippines was once called Islas de Los Pintados, “Islands of the Painted Ones,” by the Spanish upon their arrival to our islands in 1521. They noticed that men and women were heavily tattooed from head to toe. Commonly referred to as batok/batuk, these marks denoted a person’s importance, rank, wealth, and role in society.

Our islands have approximately 4000 years of tattooing practice based on archeological finds of bone tattooing implements found in Cagayan Valley that were carbon-dated to this era. Unfortunately, the vast majority of our skin marking practices were eradicated during the Spanish rule that lasted for an oppressive 333 years. It has now been 500 years since they set foot on our islands. The damage they caused to our cultural practices has been severely detrimental, to the point of nearly complete erasure in our islands except for only a handful of ethnolinguistic groups who have preserved their tattooing practice. Most of these groups reside in the northern part of the island of Luzon and some parts of the southern island of Mindanao. The Philippines were subsequently colonized by the Americans and the Japanese in the last 500 years. The effects of these occupations negatively-impacted our people and erased many of our cultural traditions, particularly tattooing which they viewed as the work of the devil or of an uncivilized race. The Spanish brought Christianity to our islands, replacing thousands of native gods and goddesses. Our oral history was replaced by stories from the Bible. Our prayers were replaced by words from the Roman Catholic Church. They cloaked our old belief system in the Catholic faith and forced us to change our ways completely. The Americans brought education to our islands, viewing us as uneducated savages. They imposed western ideologies on us, forcing us to forget our language and our way of life. This was the experience for the vast majority of the people on our islands. As a result, modern Filipinos are often culturally lost, insecure, and unintentionally appropriate practices from other cultures in an effort to fill the void left by colonization.

The struggle to recover this tattooing practice in its proper cultural context has been the focus of my teacher for over 30 years now. After hosting Manong Lane for several events, I saw how he was heavily burdened, often single-handedly taking care of all aspects of the practice from educating to bestowing markings, as well as administrative aspects of scheduling to accommodate our community. One day I offered to help stretch and clean up. I continued to show up and help. Organically I was invited to join his apprentices. Since then Manong Lane has become more than my teacher, but my big brother and friend. He possesses the wisdom of a sage, but will still sit down and have a drink with you.

I have been Manong Lane’s apprentice for 3 years now. I have 4 college degrees, but in this practice, I often feel like I am literally in a lifelong Ph.D. program. Not only am I challenged mentally, but also physically. Imagine having to plank for at least two to three hours at a time because it is pivotal to stretch and hold the skin firmly so that the practitioner and the tools can make clean accurate marks. I often refer to myself as a professional groper because I have had to stretch the skin in some (ahem) interesting places. I have also learned how to make tattoo implements by hand which is quite tedious since the ancient bone tools can’t be bought at your local store. I have come to enjoy the wealth of our oral histories that are attached to these designs, stories of gods and goddesses, migrations, rituals, and adventures of my ancestors that instill immense pride in me. The stories we learn are not just from my own ethnolinguistic groups, but a lot of oral traditions that span our whole archipelago. Part of what I have learned is how to read those markings on the skin, which has illustrated our larger connection to the peoples of Oceania.

I have traveled with Manong Lane , and together we have had a lot of misadventures, like losing our luggage in Europe, experiencing weird accommodations, and traveling to places where we barely know the language. He has introduced me to many different cultural tattoo practitioners across the globe and I have experienced what genuine cultural exchange is. We are more connected than different from each other. Through these connections, I have learned that the Pacific Ocean was a superhighway for our ancestors. To quote Disney’s Moana, “We were voyagers!” I suppose to some extent we still are. As I have learned from Lopaka Kapanui, a master Hawaiian storyteller, “Not all knowledge is learned in one school.” and one of my fellow students and a hand-tap tattoo practitioner from the Talaandig ethnolinguistic group, Piper Abas, has said, “There are many more [people] that hold our knowledge. The knowledge of your ancestors is locked up in tattoos .” In my apprenticeship, I have drawn wisdom from my elders, my mentors, my teacher, other cultural practitioners, as well as my fellow apprentices. Along with my ancestors, they are all my instructors.

Through this work, I have witnessed numerous ceremonies for people who yearn to connect with their ancestors. Everyone who has been tattooed on our mats has come with somewhat different intentions. Some want a deeper connection with their family and direct ancestors. Others want guidance and protection. While some just want to learn more about our pre-colonial culture. The effects of the practice, however, are universal. All who have received these ritual tattoos,myself included,have been transformed. Each one of us has become an emissary of the practice, gaining visual literacy of our markings, and learning our oral history. Recovering our ancestors’ markings has gifted us with distinct pride and awareness of who we are and the proud people from whence we came.

When I reflect on my tattoo journey, I realize that through receiving my markings, I have shifted away from an individualistic worldview to a collective and community-based way of thinking. This shift deeply conflicts with the Western mindset with which I was raised, one that emphasized my individuality, how to stand out, how to be unique, and how to think solely of myself. Having received my tattoos, I understand that, as I wear them, I have responsibilities beyond myself; these marks represent my family, my community, and most importantly, those who have come before me. The more I become literate in our practice of skin marking, the more I understand the wisdom of my predecessors.

Being Manong Lane’s apprentice has changed my life for the better in more ways than I can articulate, it has given me cultural pride, life path, and purpose. All those years ago when I was getting tattoos for rebellion, now it has a brand new prerogative in my life. My body holds the wisdom of those who have come before me. These markings tell our creation story of how our people were amazing navigators on the vast Pacific. I have dedicated my life to this practice. I will continue to learn and seek knowledge to restore, revive, and sustain our tattooing practice, so that one day, perhaps in the time when I have my own apprentices, the marks of our ancestors will be readily understood and embraced by our people once again.

About the Creator

Natalia Roxas

Natalia Roxas: Photographer.Writer.Wanderer. Filipino Gastronomy Advocate. Apprentice to Lane Wilcken (pre-colonial hand-tapped tattoing.

www.nataliaroxas.com // IG:@nataliawanders

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.