Inside The Stanford Prison Experiment That Unveiled Human Psychology's Darkest Depths

The Stanford Prison Experiment transformed ordinary people into monsters and was designed with psychology and science in mind.

Staff Sergeant Ivan "Chip" Frederick of the United States Army was having some difficult times in October 2004. He had been implicated in the well-known Abu Ghraib prison torture scandal that broke out in March of that year, and during his court-martial, shocking information regarding sexual humiliation, sleep deprivation, and prisoner maltreatment was revealed.

Stanford psychologist Philip Zimbardo was one of the witnesses Frederick called to defend him, and it's possible that this is why he only received eight years in prison for his crimes. Zimbardo contended that Frederick's actions were more likely a response to the conditions that the higher-ups had permitted to emerge in Abu Ghraib than a reflection of his personal nature.

Under the correct conditions, Zimbardo clarified, nearly anybody could be made to perform some of the acts Frederick was accused of: beating captives while they were nude, defiling their holy objects, and making them masturbate while wearing hoods over their heads.

Zimbardo maintained that Frederick's actions were not the singular acts of a "bad apple," as the Army had tried to ascribe blame, but rather the expected result of his mission.

Because he had been involved in prisoner mistreatment himself, Zimbardo was able to speak before the court-martial with a certain amount of experience.

He had served as the "warden" of a fake jail in the basement of Stanford University's Jordan Hall for six days, from August 14 to August 20, 1971.

With funding from the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, Zimbardo created a psychological experiment in which twelve otherwise normal young men were randomly assigned to be either a prisoner or a guard for a two-week role-playing exercise. The goal of the experiment was to better understand the dynamics that drove the interactions between prisoners and their guards.

The Stanford jail experiment under Zimbardo's direction devolved into a conflict between the torture-loving, cunning guards and the suffering inmates.

The findings were documented and extensively disseminated, establishing Zimbardo as an authority in his field and exposing a startling truth about how little it occasionally takes to transform humans into monsters.

The History Of The Stanford Prison Experiment

Ten years before to the Stanford jail experiment, Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted an experiment in 1961 to see if certain individuals would be comfortable giving electric shocks to complete strangers.

The famous Milgram experiment demonstrated that certain young men may be coerced into shocking someone to death—a disturbingly simple task given that they are taught to feel they may have done so, even though no participants were ever hurt.

Further investigation into situational behaviour and the idea that we are only as good or awful as our environment will allow us to be is made possible by the results of this experiment. Although he was not there for the Milgram experiment, Philip Zimbardo studied psychology at Yale until 1960 and was prepared to further Milgram's findings at Stanford by 1971.

At that point, he was given a commission by the U.S. Office of Naval Research to investigate the psychology of confinement and power dynamics between guards and prisoners. After receiving the funds, Zimbardo immediately began working on the Stanford jail experiment.

The experiment was conducted at the Stanford campus, in the basement of Jordan Hall. There, Zimbardo used internal walls to build up four "prison cells," a "warden's office," and a number of communal spaces for the guards to utilise for relaxation. Additionally, there was a little broom closet—a detail that would come up later.

In order to find volunteers for his experiment, Zimbardo published an advertisement in the Stanford Daily requesting "male students" who were willing "to participate in a psychological study of prison life." The advertisement offered $15 per day in pay, or around $90 in 2017.

Zimbardo meticulously selected his volunteers for the experiment once they applied in order to weed out any possible bad apples. Participation was denied to anybody with a criminal record, no matter how small, as well as anyone with a history of behavioural issues and psychiatric abnormalities.

Ultimately, Zimbardo was left with 24 healthy males of college age who showed no signs of violent or other bad inclinations. The Stanford jail experiment started with the subjects being randomly allocated to either the guard group or the prisoner group.

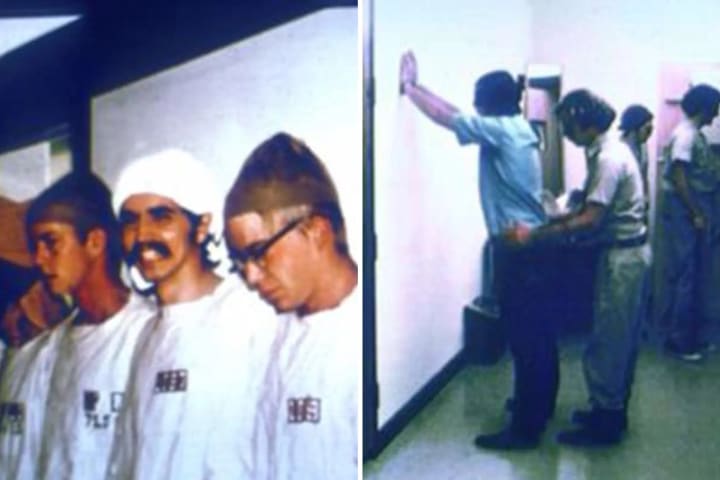

Zimbardo gathered his twelve guards for an orientation briefing the evening before the experiment. He gave them clear directives about their responsibilities and boundaries: guards would be divided into three eight-hour shifts to ensure that the prisoners were watched over around-the-clock.

They received wooden batons as a sign of power, mirrored sunglasses, and military-surplus khakis. The guards were all instructed not to beat or otherwise mistreat the 12 inmates under their charge, but they were also given a lot of latitude in how they handled them.

The Palo Alto Police Department showed up at the residences of the targeted inmates the following day and brought them into jail. The 12 males were searched, had their mugshots taken, and had their fingerprints taken before being checked into the county prison.

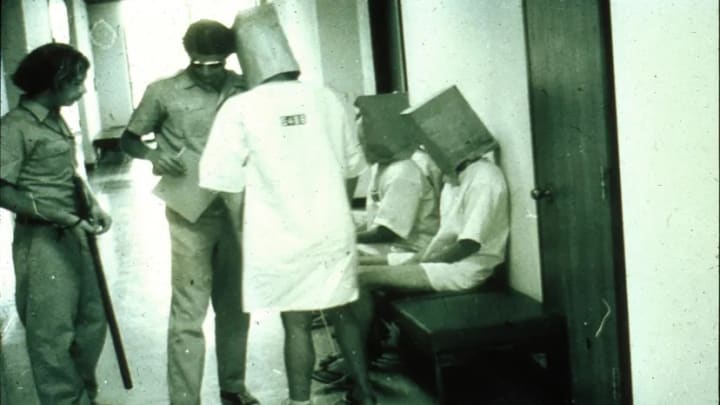

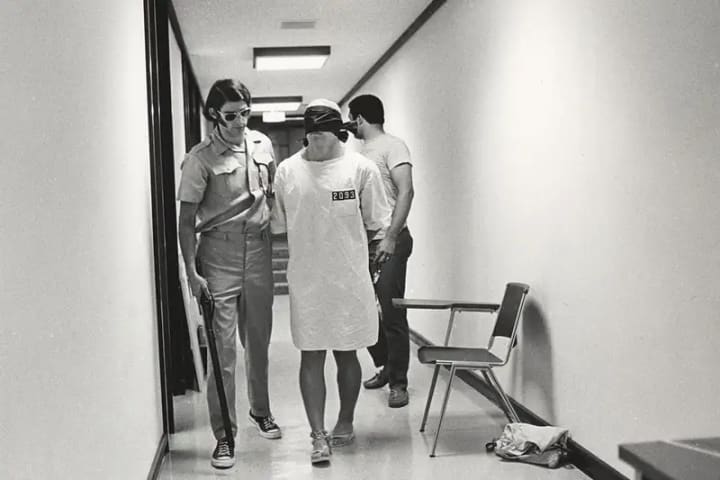

They were eventually brought to the Stanford campus and led by security into the basement, where they were met. Inmates were instructed to wear big stocking hats and were issued smocks that were too small. To emphasise that each of them was a prisoner, a small chain was looped around his ankle. They were divided into groups of three and given instructions on how to follow them.

Large numbers stitched onto the inmates' smocks were only one of several strategies used to make the convicts feel inferior to the guards; guards were instructed to refer to the detainees solely by these numbers rather than giving them the respect of names.

Both sides had completely internalised the rules by the end of the first day of the Stanford jail experiment, and they had started acting towards one another as though their extraordinary power dynamic was always there.

Uprising and Rebellion

Though both sides had internalized their roles and some inmates looked to grumble at the monotony and the arbitrary character of their guards’ directives, the first day of the Stanford prison experiment had gone by more or less uneventfully.

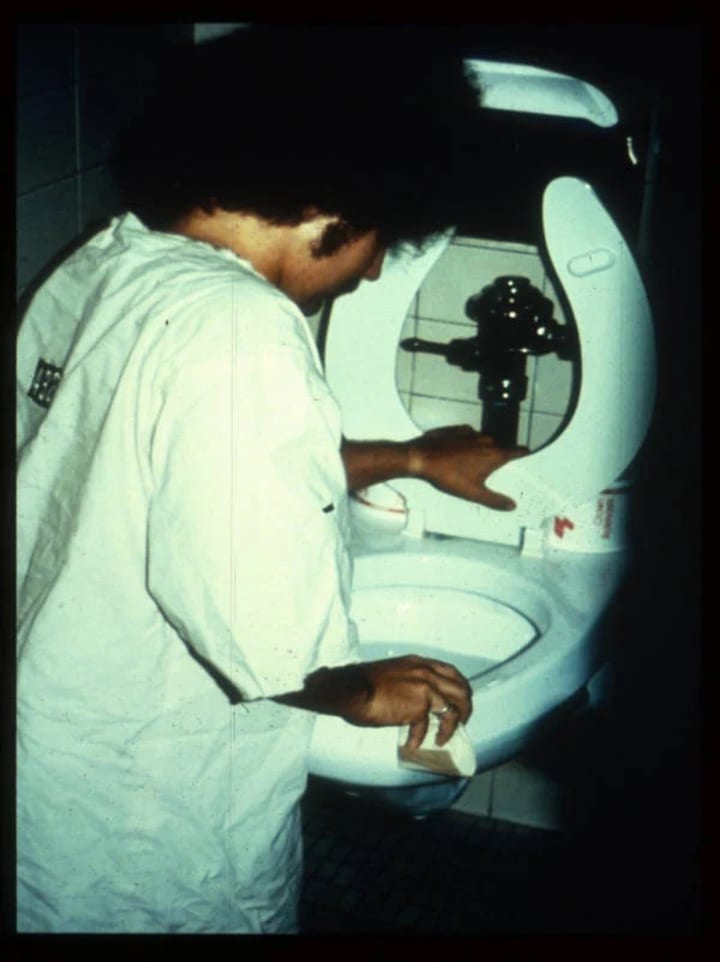

It was not at all possible for prisoners to have contraband that early in the experiment, but still, they would occasionally be taken out of their cells and searched. Most of the guards were obnoxious and patronising. They sometimes insisted on convicts repeating their numbers in order to emphasise how inferior they were. Penalties were being applied, such having to hold stressful positions for prolonged periods of time, and menial duties were being allocated.

By the first night in custody, the guards had made up their minds to punish the less cooperative inmates by removing their beds and making them lie on the freezing floor. Additionally, they kept the prisoners awake by making noise in the common area next to their cells.

Prisoner #8612 began exhibiting indications of a breakdown around midday on day two. Zimbardo had to intervene to calm him down when he began to yell and become furious. The decision was taken to release the prisoner from the research for his own benefit since he would not calm down.

This came in the guise of a "parole hearing" followed by a protracted stay in the broom closet, which was serving as a place of isolation. The lengthy and difficult release procedure was designed to reinforce the idea that the jail was an all-powerful establishment where prisoners had no rights.

Remember that everyone was free to leave whenever they wanted to, at least in theory, and that this was all voluntary.

The other eleven inmates were in a riot while prisoner #8612 was being processed out. Inmates had already been incited to defy commands and vacate their cells by the guards' arbitrary and brutal treatment. When their numbers were called, they would not respond.

One cell's occupants wedged a mattress up against the door to create a makeshift entrance. That night, things had become so terrible that a few guards, who could leave after their duty and go home, offered to stay late to put down the uprising.

Following the departure of the clinical professionals who were overseeing the experiment, the remaining guards used a fire extinguisher to strike the inmates and moved them to different cells in order to cram more people inside. For "good" prisoners who hadn't taken part in the rebellion, the unoccupied cell was set aside. On the other hand, suspected ringleaders spent hours alone in isolation.

In regular cells, inmates were given buckets for relieve themselves in instead of being allowed to go to the toilet. After that, the buckets were left in the cell untouched for the whole night. The detainees were made to stand in stressful positions for hours at a time without clothing the next day by the guards.

Too Dangerous To Proceed

By the third day of the Stanford jail experiment, things were falling apart quite quickly. About one-third of the guards, according to Zimbardo, showed evidence of true sadism on their own. These guards would often devise creative methods to punish the defenceless prisoners, and they would encourage the other guards to do the same.

Both the guards and the prisoners, who had only been given their positions at random a few days before, started to identify with their side and function as a unit. A few days later, the guards were taking on extra shifts for free and growing more suspicious, while the majority of the prisoners had organised a hunger strike in protest of their living circumstances.

Zimbardo himself ordered the underground prison to be dismantled and transferred upstairs after a rumour spread that prisoner #8612 was planning to conduct a jailbreak with a small army of sympathisers. Zimbardo remained in the basement, waiting by himself for the assailants. Later, he added that if the man had truly turned up, he would have told him the experiment was over and sent him on his way.

Zimbardo was now totally engrossed in the experiment himself. He eventually acknowledged that he would never be able to remain impartial in his capacity as jail administrator, and as a result, he became entangled in the fantastical universe he had constructed for his test subjects. Zimbardo saw that he was growing obsessively interested in the experiment's direction and the fresh discoveries that each day would bring.

When some prisoners started acting suicidally and seemed to be losing their sense of reality on day four, Zimbardo found the scenario intriguing enough to invite his partner, a PhD student in psychology, to check into what was going on. Christina Maslach, a 26-year-old lady, expressed her disgust at what she observed.

Every time someone was brought in from the outside, like prisoner #416, who took the place of #8612, in the past, there was a period of normalization.

However, #416's protests over his treatment resulted in his being placed under lockdown in isolation, where the guards would beat on the door in shifts to torture him. Prisoner #416 had become sufficiently shattered by the time he emerged from the solitary confinement closet to begin to accept the jail routine as the standard.

However, Maslach could not be broken or imprisoned in that way, and her newfound understanding of the situation startled her partner into realising that she was witnessing his nightmare. To the dismay of his guards, who had come to enjoy the authority they had been abusing for the whole week, Dr. Zimbardo announced the conclusion of the Stanford jail experiment on day six.

After that, everyone remained so insane that it took an entire day to "parole" the remaining prisoners; yet, as previously said, the experiment was completed, they were no longer receiving payment, and they could have just left.

The Stanford Prison Experiment's Aftereffects

The Stanford jail experiment quickly rose to fame as a classic study of power relations and human psychology. The most startling discovery may have been that research participants very immediately internalised their roles to the point that they appeared to have forgotten they even had lives outside of jail.

Prisoners endured horrifying violations of their human rights without, for the most part, begging to be released, while guards behaved with extraordinary harshness, acting as though they would never have to answer for their crimes.

If you find this piece interesting, please leave a like, or even a tip. Your support means a lot to me as a writer!

About the Creator

Victoria Velkova

With a passion for words and a love of storytelling.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.