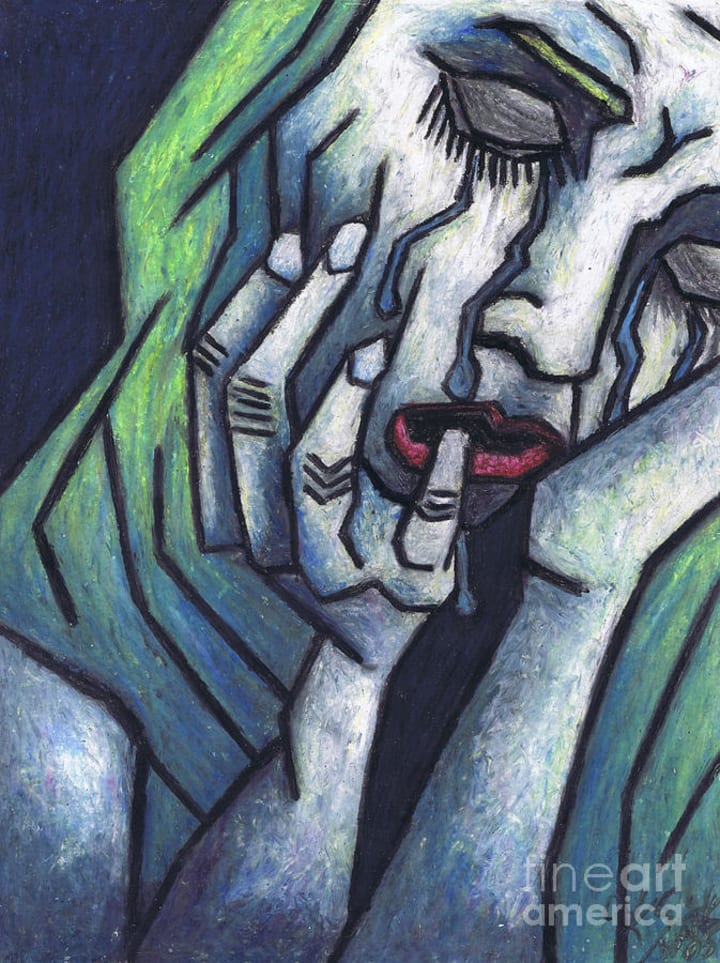

Children of La Llorona

A variation of the story that used to keep me up at night...

Here in south Texas, most children grow up hearing the story of La Llorona. Bedtime stories on the border are not dainty nursery rhymes but stories that help us understand the danger and beauty of the world. From the safety of our lamplit rooms we begin to understand the commingled pain and joy of life. When we were children the stories simply seemed transportive: terrifying, amazing, portals to another time or place. It wasn’t until I was older that I realized the storytellers of my family - grandmothers, mother, aunts - were telling me something of this world.

Though I have never met La Llorona, never had children or lost them, I understand now the pain of lost love. The treachery of life’s injustice. And when I stand near a softly flowing river in the evening and hear a wailing on the wind, I feel my own pains and joys connected to the beautiful and deep, ever-nourishing well of story.

My favorite stories are those that have been passed down orally, over long and longer periods of time. Though occasionally transcribed into text, these stories exist beyond any written version. La Llorona is one such story. There are many versions in the Spanish-speaking world. But the version my tia told me, wise woman that she was, her fingers on the clear source of the world, is different than most I’ve heard before.

Her version features the duende, other denizens of Latin American folklore who dance through many tales. It gives a depth and compassion to La Llorona that is often missed in others’ tellings. Though I believe in the multiplicity of tellings, I want to share mine, not only in defense of La Llorona, here the brave but naive dreamer Tiora, but because of its perspective on colonialism: not just of people, but of their hearts, minds, and descendants.

16th Century Mexico. By a pool beneath a cascading waterfall, Tiora, a young idealistic girl with dark, flashing eyes, wrung the previous week’s stains out of her brother’s clothes. She worked meticulously at her chores, but her eyes darted to the other girls from her village squatting along the bank of the pool, laughing and splashing each other with the cold, clear water. They were teasing each other about the handsome Spanish soldiers, recently arrived to the new military fort. The girls all seemed to have a crush on one man or the other: the soldiers' gleaming armor, powerful mounts and arms, and dark hair had them all on the brink of laughter.

Tiora smiled to herself but kept apart from the talk. Deep down, she knew she was destined to marry one of these Spaniards. She had always dreamed that one would take her away from her small world, to see the great wonders of Europe the girls only heard spoken of in awed whispers by the old folks and tale-tellers. But she didn’t want to say this and be like the other girls. She never wanted to be common. She believed she had a special destiny, and she kept this special destiny a secret for herself.

As Tiora and the other girls walked back into town carrying their grass-woven baskets, a patrol of Spanish soldiers crossed their path. The girls could hardly contain their giggles as they watch the men parading past on horseback. Tiora’s eyes fell on a man at the front: strong, handsome, with a smile in his eyes, he was everything she’d ever dreamed of. He looked her way and boldly, she held his gaze. He smiled at her, his eyes crinkling at the corners.

That evening, Tiora and her friend Iome walked up to the fortress. Tiora’s brother accompanied them as always, the two girls would never have been permitted into the fortress without a chaperone. They were accustomed to going up on evenings, selling their handmade pottery and sewing to soldiers and their families who longed for the touches of home.

Tonight, however, Tiora had a mission. She watched the soldiers leaving their mess, picking each face out of the crowd until she saw him again, the handsome soldier from the road. She squared her shoulders and took a deep breath and marched toward the men before Iome or her brother could stop her. She walked right up to the men and asked if they would be interested in her pottery.

They mostly laughed, and a few gave her appraising, dirty looks. But the soldier from the road grinned and nodded and followed her to her and Iome’s blanket spread on the ground. He looked through each piece carefully, his eyes darting back to Tiora from time to time, hesitant to speak. He was kind and gentle, and introduced himself to Tiora’s brother respectfully. He told Tiora that his name was Diego, and that he would like to see her again.

So began what seemed the best summer of Tiora’s life. She and Diego were soon inseparable: eating lunch and murmuring together in the great grass field by the fortress walls, going for stolen walks by the water. They knew some of each other’s language and taught each other more. Tiora would rush out of the village on mornings Diego’s troop left on patrols, watching his dazzling armor and handsome figure racing across the fields. Diego would reign in before the village and look for her, every time. They would share a smile that only they understood. They loved each other, that heady tumultuous rush of first love, and they spent their working days waiting for the moments they could share with each other again.

Eventually Tiora’s wildest hopes were realized. Diego proposed marriage to her beside the river. He told Tiora that he always wanted a family, and though he never expected to find the woman of his dreams here, he knew now he wanted to start one with her. He assured her that his mother was arriving from Spain shortly, to assist him with the wedding and to help Tiora with the children they’d have. Tiora happily accepted without another thought.

She was the envy of all the village girls: as they prepared her for her wedding ceremony they could barely contain their jealousy. Tiora was lost in daydreams of Spain, of traveling to see the palaces and cathedrals Diego told her about, and of the beautiful children she would have with him, bridging their two worlds.

Diego’s mother Isabel arrived from Spain the day of the wedding, her boat sunk low in the water by her huge trunks of finery. She complained of the smell, and was stern and cruel to the indio laborers employed to carry her belongings. When she met Tiora, she stopped cold. She had not understood that her son was set to be married to one of these people she called “savages.” Tiora was hurt, but defiant. She told the woman she was no savage. Diego tried to smooth things over, but the damage was done. Isabel believed Tiora insolent, and Tiora knew her mother-in-law hated her for who she was.

After the wedding, Diego assured Tiora that his mother would warm up to her eventually. But it never happened. Tiora relocated to living in the fortress with Isabel as her sole companion most of the day. Miserably she watched as her old friends continued to come and go from the fortress freely, while she was trapped indoors with Isabel, wearing constrictive Spanish clothing and being tutored in comportment and the Spanish language.

Diego was still good and kind to Tiora, but he was torn, accustomed as he was to trusting his mother’s opinion. When Tiora became pregnant, both of them hoped it would make Isabel finally soften up. But it only made Isabel hate her more. One day Tiora caught a glimpse of Isabel in her room, chanting something in Latin, burning sweetgrass and passing her hands over a gold icon of Madonna and child. Tiora felt a terrible pain her belly at that moment. Isabel saw her at the door, and glaring at her closed it.

As Tiora’s pregnancy advanced she became more and more uncomfortable. She attributed it to the constrictive Spanish clothing and habits Isabel forced her to keep, and begged Diego to let her go to her mother for her pregnancy remedies. But Isabel told Diego that Tiora intended to curse the child by going back amongst her “heathen” people, and wouldn’t let Tiora out of her sight. Shortly before Tiora was due to give birth, Diego was called away on a long campaign, a month at least. Tiora pleaded with him not to go, but he did.

So Tiora gave birth in a stuffy, miserably hot room, attended only by Isabel, while Diego and his troop went out into her homeland, ransacking indio villages that refused to convert to Catholicism.

Tiora’s children were born: twins. And they were grotesque. They looked nothing like babies. They had wrinkled, goblin-like faces, the hands and feet of fully grown men, and sharp, pointed teeth that they gnashed wildly. Tiora screamed when she saw them, and then passed out from the pain. When she awoke, she saw Isabel had stuffed them bizarrely into christening clothes. She told Tiora she thought about killing the cursed children when she saw them, but instead she wanted to keep them alive, to show Diego the hideous offspring that comes from intermarrying with Tiora's kind.

Tiora begged to see her mother, but Isabel kept her confined to her bed. Tiora only saw the duende twins (for that is what they were) occasionally; Isabel kept them out of sight. Tiora tried to nurture the children or show them some kind of love, but they barely seemed to recognize her, and violently flailed if she tried to touch or calm them.

When Diego returned home and saw his newborn sons, he was horrified and distraught. Tiora pleaded with him to understand and believe her, she didn’t know why this happened to their babies, she had never seen children like this in her life. But Diego would not. He accepted his mother’s story: Tiora had taken him in through heathen witchcraft, preyed on his desire to have children, and cursed their offspring. Diego expelled Tiora from the fortress, sending the duende with her. Isabel was triumphant.

Tiora returned to her home with the duende. Her family and friends tried to help her and the children. But they wreaked havoc everywhere they went and had to be restrained to stop them from hurting people. One day Tiora, desperate for a rest, drifted off to sleep. When she awoke, the duende had escaped: and brutally attacked her friend, Iome.

Tiora’s friends and family were torn; they wanted to help Tiora, but they couldn’t permit the duende to stay in the village. Many of the girls blamed Tiora for Iome's mutilation; their jealousy at her for having married Diego mutated into cruelty, insinuating that these were Tiora's chickens coming home to roost.

Tiora raced across the wild land, trying to recapture the duende. She finally managed to do so; by now they seemingly recognized her and were almost attached to her. They even seemed more docile, placated by the violence they had recently wrought. Tiora used this to lure them to the pool by the waterfall, where she softly sang to them, before holding them both down under the water, placing heavy rocks on top of them to drown them.

But Isabel’s curse had not run its course. Back at the fortress, because of the magic bond she created, Isabel could sense that Tiora was about to break the curse she laid on the children by killing the duende. She began to murmur a prayer.

At the waterfall, Tiora watched in spite and relief as the duende suffocated, grappling for air. But as they died: their faces softly morphed into human faces, their hands and feet returned to normal size, their teeth receded and beautiful black hair grew and swirled around them. As both boys took their last breath, they became her true baby boys, and they stared up at her with the shock of betrayal as they drowned. Tiora quickly pulled the stones from their bodies, but as she dragged them from the water, she knew they were already dead. Weeping, she lay on the shore with them, her beautiful, perfect, dead baby boys.

Years passed. The Spanish fortress grew into a Spanish colonial town. The river shimmered placidly under the moonlight, running past the fortress. Diego, now remarried to a Spanish woman, carefully watched his children, keeping them from running out of the fortress down to the river. Everyone knew the stories… that something lurked by the river, preying on the Spanish children. Diego’s wife dismissed it as a ghost story.

But Tiora was there. Hiding in the long grass, eyes full of hate and despair, she watched as two young boys and a girl broke away from the fortress, kids looking to play out in the rushing river. Tiora wailed, long, low and moaning… a sound to chill the bones. The children looked around, terrified, and Tiora laughed. The children, deciding they'd had enough scares for an evening, turned to head home - and that's when Tiora pounced! She dragged them down to the river to drown, as her own beautiful children had drowned: her revenge.

And she remains there by the river still. Now people hear her wail and call her La Llorona, but she was only a woman once, who dreamed of love and life and a family of her own, and was denied them all.

About the Creator

Kate Phillips

Texas writer full of stories, builder of worlds, vanquisher of the Sunday scaries. she/her

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.