The cabin in the woods had been abandoned for years, but one night, a candle burned in the window. Small creatures scuttled away, disturbed by a human presence for the first time in their lives. She struck another match and lit a candle for the table too. And then more candles for the shelf by the door. Soon there was a strong enough glow to keep only the four corners of the room in shadow.

Something caught her eye, and she froze in front of the window. A shape moved through the bushes? There were no other people for miles. Or had she just glimpsed the action of her own reflection?

She reached into the bag on the chair and placed the contents onto the table, one bottle at a time. First there was the cheap vodka she’d grabbed specifically for that evening, and the cheaper cola to accompany it. Then the champagne she’d been saving for a day when there was something to celebrate, and the bottle of Barbaresco she had chosen for a second date that never happened. A Brooklyn gin that she couldn’t really account for. And finally, the half a bottle of Tia Maria a friend had left at her apartment. Still, there was one bottle missing, one bottle left to complete the drinks menu for the weekend, and it was the main reason she had come to the cabin.

The cabin was not as empty as she thought it would be. She checked the bathroom and the bedroom too. Her sister had said she’d been and taken what she’d wanted not long after the funeral at least two years ago, but she can’t have wanted very much. Furniture, piles of books, shelves cluttered, hats and coats on hooks, mirror above fireplace and boots by the door; all remained as evidence Uncle Brendt had lived here. But it would be just like her sister to take the one thing that she wanted. If it was still there, it would be in the cellar.

She took out her phone and swiped the screen with her thumb. There were messages. She tapped at her phone again and held it to her ear. Hi, it's Jenny, she said, I’m sorry but I’m not going to make it tonight. No, I’m just not in a good place right now, but don’t worry. I just need to clear my head for a couple of days. I’ll text you. It’s fine. Ok, bye.

Jenny switched to flashlight mode and lifted the door to the cellar. It had always given her the creeps, descending one creaky step at a time, pushing through the cobwebs. More cobwebs than before. The way the shadows shift.

Uncle Brendt’s armchair faced her at the bottom of the steps. That was where they found him, at least a year after he’d died. He must’ve been just bones, but he was never much more than that, at least not physically. His presence was immense in other ways.

The flashlight swept across the walls. There were things in the cellar that she expected her sister to claim but nothing much seemed to be missing.

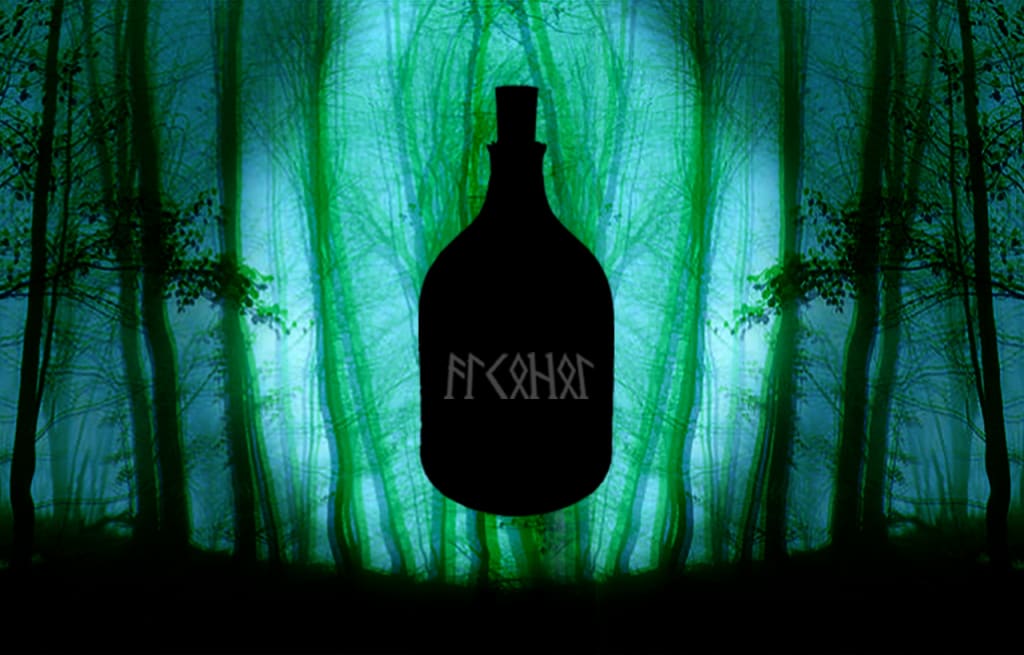

She opened the cabinet and there it was. The pale green ceramic bottle, almost like a vase but sealed with a cork and etched with what she had thought was Russian characters when she saw it in her twenties, but now she was not so sure. This is the magic potion, Uncle Brendt had told her, when we are done with common age and wisdom, we will try a glass of green madness.

Jenny took the bottle in her free hand. It was the absinth (Bohemian-style without the ‘e’ and undiluted) from her uncle’s time in Prague. That’s why she had come to the cabin. That was the missing bottle from her liquor line-up. She picked out one of the Norlan heavy tumblers and placed it upside down over the neck of the bottle and climbed back towards the candlelight.

Where to start? The wine probably made the most sense. She put the champagne outside to chill. She probably wasn’t going to risk the dregs of the Tia Maria. So, she imagined she was going to go; wine, vodka, gin, absinth and then wash it all down with champagne. Jenny was not a big drinker, so this was going to be a challenge. She had never drunk so much it made her sick, dizzy, yes, but not physically sick in the way that some people might be crouched over the rim of a toilet. She’d always imagined she might fly down to the rainforest and do the ayahuasca cleanse, gulping a psychoactive brew and spewing up until reaching a state of transcendent hallucinations. Jenny poured her first glass of Barbaresco. This was the beginning of her alternative intoxication ritual. She was going to drink and drink until she was ready to vomit.

She raised her glass, here’s to you Uncle Brendt, she said, and took a deep swig. This was the first task of the alcohol, an aid to remembering her uncle in the place where he had spent the last years of his life and the first years of his death. Again, something seemed to move outside the window, the leaves of the bushes shivered.

Uncle Brendt was a wannabe Bohemian. He’d spent his twenties hopping from one sofa to another in San Francisco, making zines he sold at City Lights or left as free gifts on the shelves of the Presidio Library. He attended Panhandle peace protests and pilgrimaged his way across twelve states to Vermont’s Brautigan Library before disappearing to Europe for a decade of debauchery.

The wine was done. The bottle was empty. Jenny poured in the vodka and topped it up with cola. It’s not impossible to drink vodka neat, but why would you? It’s not a taste you want to savour. It smells like a household product. Something to clean you out.

Uncle Brendt returned from Europe in time for Jenny’s graduation. He came with stories of sleeping on the streets of Montmartre, of collaborating with surrealist alchemists in Prague, of spending restless nights with David Bowie and Romy Haag in Schöneberg. They weren’t just stories they were myths. They occupied the same space in Jenny’s heart as any fairy-tale. It all felt like a far cry from an isolated cabin in the Catskills.

Jenny sorted through one of the piles of books, picking up some to flick through the pages. She wondered if her uncle had made it through all of them. He had read a book as a child called My Side of the Mountain; it was about a boy running away from New York to live in the wilderness of the mountains. He said that planted the seed for him, it just took a while for that seed to grow.

Throughout her twenties, Jenny had visited her uncle at the cabin. Sometimes with her sister and mom, sometimes alone. She would listen to his stories and imagine herself in his place. If her sister or mom were there, then they would shake their heads and scorn him for being irresponsible.

The plan wasn’t to drink all of everything. The plan was to consume a good range of drinks and build up to being satisfyingly sick. Jenny set the vodka to one side and poured out a couple of measures of gin. She hesitated with adding the cola and decided she would drink it neat. She raised the glass to herself in the mirror, gin gin, she said with a giggle.

He’d died in his favourite chair in the basement. Two of his friends from his time in New York found him. He’d opened an esoteric bookstore off Bleecker Street, but it was a venture that didn’t last more than six months. Jenny’s mom had said they weren’t really friends, that Brendt had owed them money and that they’d been asking after him for months until they finally tracked him down. But Jenny’s mom was always quick to paint the darkest picture of her brother. In any case, the two friends were at the funeral, and they weren’t asking about any money there. Jenny had approached them and thanked them for attending. One of them, the one with the gray tufty beard, had said something that still puzzled her.

The gin had gone down well. The candles were going well too, melting almost halfway through the wax. Jenny was feeling dizzy. It was absinth time. She took the ceramic bottle in both hands, stroking the engraved symbols with the tips of her thumbs. She twisted free the cork and poured out what looked like a luminescent green medicine. It looked miraculous in the candlelight. This was her first encounter with absinth, but it was a moment she was too drunk to really savour, so she lifted the glass and took a gulp. Instantly she felt a tremor in her stomach, a churning of several flavours mixing through each other. The rumble of a volcano. She took a swig from the cola bottle and downed the rest of the glass. Down she went.

It wasn’t clear how Uncle Brendt had died. What had killed him. Jenny’s mom had always warned that the partying would catch up with him. After his death she continued to subtlety characterise his fate as a morality tale. Some siblings are different sides of the same coin, but Brendt and Linda were like completely different currencies.

Jenny woke up with strange shapes in front of her. Her cheek was pressed against one of her uncle’s rugs. She steadied herself on all fours, saw the huge pool of sick, burped, hurled up even more and collapsed back onto the rug to pass out again.

Maybe he died from happiness? Jenny wondered if he had just done everything he’d wanted to do, lived his full life, and there was just nothing left for him to do. That was the sense she got when she last saw him. The eager desire for mischief had been replaced by a serene contentment. Is it possible to die from feeling like your life is complete?

The pool of sick had vanished. Jenny looked around, disorientated. It was darker now, several of the candles had gone out. She felt in front of her with her hands. There was a strange dampness there. Then she heard something, a kind of gargled growl coming from the direction of the corridor to the bathroom. Some old pipes at work?

Jenny stumbled onto her feet and gulped from the cola bottle. There was something strange going on. Movement outside the window. The bushes were moving, they were passing by the window, the world was spinning. She lurched to the side, disorientated. Get a grip. Relax. You’re just very drunk, she told herself. She wondered what kind of state the bed might be in. She needed to lie down.

She staggered into the corridor and was almost at the bedroom when she saw it. There was someone stood there, outside the bathroom. The figure turned its head towards her. Jenny took a step back and almost fell, she bounced from the corridor wall and pulled open the cabin door. The world was spinning too fast now. She stood there in the open doorway. She could jump but it would be like throwing herself from a runaway train. Something was flashing out there like a gleaming light. It was the champagne bottle whizzing past at head height every two seconds or so. She slammed the door shut and faced the corridor. The human shape emerged. It was a somewhat human shape but not quite. The skin, from head to toe was an oozing vomit. Two shiny carrot-colored eyes peered out from it. It was Jenny’s pool of sick come to life and walking slowly towards her.

What do you want? She almost screamed. Want you, it replied. Jenny walked backwards leading it away from the corridor and then rushed past the vomit creature to the bathroom, locking the door. She ran the faucet and splashed her face. Was this real? How was this real?

Sick was creeping under the bathroom door. Jenny grabbed a towel and pushed it back. She banged the door with her fist and shouted, what do you want from me? Want you back, it replied. The towel started to move, she pushed it back with another towel in both hands and held it there. Why? She asked. Can’t run away, it replied. She manoeuvred so that she was curled on the floor and her back pressed the towels against the bottom of the door. She closed her eyes, maybe in the morning it would all be over.

The image of Uncle Brendt sat in his favourite chair, smiling with complete contentment as his heartbeat slows to a standstill, as the flesh falls from his bones, as his bones fall apart, still smiling.

He had so much potential, her mom had said, and wasted potential needs to go somewhere, it can’t just build up inside you or it festers and eats you away. If it was a binary choice between choosing to live like her mother or choosing a life like her uncle’s, it would feel easier. But we tread our own path, not someone else’s, and that path is paved with the infinite paths we are simultaneously choosing and not choosing in every step we take.

They say, better out than in, but that’s not true of everything. Jenny opened the bathroom door and took the pool of vomit by the hand, helping it into the bath. Who are you? She asked. I am Brenda, it replied. She poured in cold water and washed the shape until it was no longer human. Then she fetched her glass and scooped the water up, drinking glass after glass. She closed her eyes. The sun was rising.

For one moment, the answers to the puzzles that had troubled Jenny started to become completely clear. She understood how Uncle Brendt had died. She made sense of what the New York friend with the gray tufty beard had said at the funeral. She could decipher the runes on the absinth bottle. She knew what she wanted from life. All those answers were there in front of her and then she opened her eyes, and they were gone. Because those answers weren’t important. She was cleansed from them.

Jenny drank the last glass. The world outside had stopped spinning. She placed the champagne bottle on the table, leaving it with the rest of the alcohol at the cabin and said goodbye.

About the Creator

Joe Evans

Just getting started...

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.