A New, Old Terror

How "I Am Legend" (Re)Invented the Zombie Apocalypse.

This is a dead horse trope that, true to its nature, refuses to stay in the grave. From vampire, jiangshi, and xidachane, the walking corpse has collected many names from many cultures. Renowned horror authors such as Bram Stoker, Mary Shelley, Ambrose Bierce, and H.P. Lovecraft have all been instrumental in influencing the exploration of the horrors of not only death but what lies beyond it.

The zombie is the personification of the uncanny valley, specifically the theory of mortality salience and pathogen avoidance. The undead’s mutilated, mutated, dismembered, and decaying state reminds us of our own vulnerability. The jerkiness of its movements sickens us because it speaks to our fear of losing control, losing our sanity, and then losing our humanity. Even worse, it has enough defects to disturb us, but it has not defected to the point that it is no longer human, preying on our disgust toward the diseased and the alarm that arises from being infected as well.

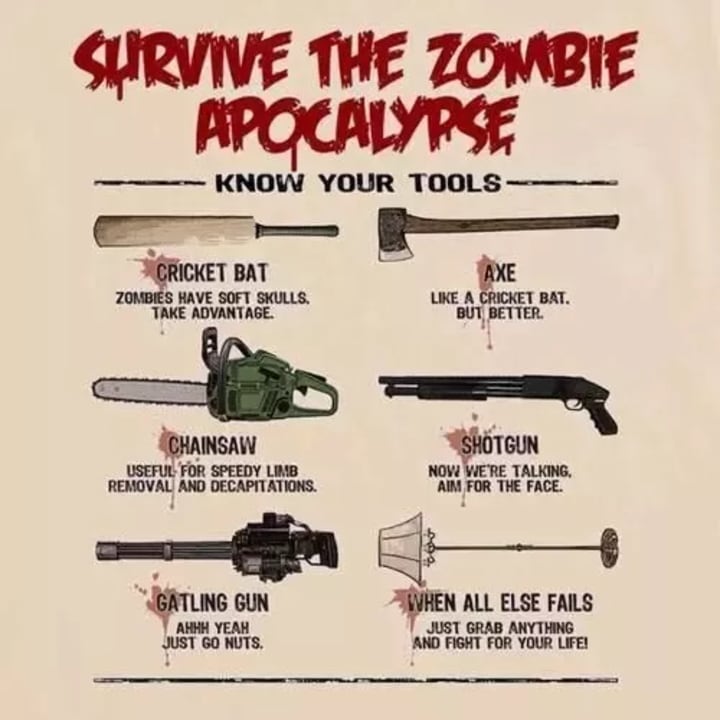

Thus, we are often relieved, even delighted, when the hero hefts a spiked baseball bat over their shoulder, readies their ax, or charges out of their shelter guns blazing, slaughtering their way through the horde to safety. Caught up in the enticement and entertainment value of mindless bludgeoning and brutality, it often slips from our mind that any one of those foes could be these “heroes'” deceased friends and family. Why is it that the legends that used to unite us now divide us? Through the characters of Virginia, Ben Cortman, and Ruth, Richard Matheson urges the audience to ponder why such violence is the expected response instead of a last resort, and why those who wish to survive must continually choose revulsion over compassion.

This compassion is represented by none other than Robert Neville's Lost Lenore, Virginia. Her name is derived from the Latin word virgo, which means “maiden” or “virgin,” and the connotations of innocence, purity, and vulnerability that are associated with those terms lead the reader to also associate those traits with Robert Neville’s beloved wife. By choosing this name, Matheson is already painting Virginia in a sympathetic light and endearing her to the audience. Additionally, he makes it a point to emphasize Virginia's selflessness through her conversation with Robert Neville during his flashback. Robert notes that “She seemed to regard [her illness] as a personal affront” (Matheson 43), which seemingly refers to how the germ is affecting her more than anyone else, but upon closer inspection, “personal” refers to Virginia’s private life and relationships. She is irritated at her sickness not just because it is an inconvenience for herself, but because it could be an inconvenience to her husband and her child, showing that she is an incredibly kind and selfless individual. The prioritization of her loved ones over herself is further demonstrated by her insistence on sending their daughter Kathy to school, despite her symptoms weakening her to the point where she admits she looks like a ghost (41) and even struggles to smile (42).

Virginia also shares her name with a Roman girl who is killed by her father to save her from being corrupted by the government official Appius Claudius Crassus, foreshadowing how Robert Neville also had to kill Virginia because she wants to kill him as a result of her disease. This demonstrates that Virginia is a victim first, and a vessel for the Vampiris germ last. Even more tragically, the fact that her first word when she is reanimated is her husband's first name and her first action is to return to her own house rather than any other house in the neighborhood implies that there is still some part of her left that recognizes him and misses her home. Her demise, and therefore every zombie’s demise, is treated not as a triumphant victory over a heartless beast, but as a heartbreaking euthanization of a devoted wife and mother.

Matheson’s attitude toward Virginia is actually quite similar to the approach that Haitian people had towards the original zombi from their folklore; a tale rooted in the traditions carried over to Haiti by enslaved Africans and their struggle to cope with the horrific cruelty they experienced in the plantations of the New World. They believed that Baron Samedi would gather them from their graves to bring them to a heavenly afterlife in the place from which they were captured and shipped away, but those who offended the voodoo deity would be a slave forever in death; a zombie. Slave drivers, sometimes former slaves themselves and sometimes voodoo priests, used the fear of zombification to discourage slaves from committing suicide out of desperation. On another, more hopeful note, a zombie could be rescued from their plight by feeding them salt. Similarly, in South Africa, the spell of zombification can be broken by a strong enough traditional healer known as a sangoma. Strangely enough, though, most modern works often eliminate this chance at salvation.

Virginia is not the only loved one that Robert Neville has lost over the course of the epidemic. This brings us to Ben Cortman. Although he is only explicitly stated to be Robert Neville's co-worker, the high level of familiarity they have with each other suggests that they were quite close. For example, Robert reminisces about "[riding] to work with Ben" and "[talked about] how Virginia and Kathy were getting along, about how Freda Cortman was about" (53), showing that the men truly trusted each other to the point where Ben regularly gave Robert rides and cared about each other's families as much as their own. Furthermore, it is telling that he is the first person that Robert runs to for a car after Virginia passes away (60), and the thought of him dying is so unbearable to Robert that he briefly imagines that "there was no wound on Ben's throat" (60) even though "there was no waking up" (60) from the reality of the situation. Whereas Virginia serves as a reminder of the underlying humanity of the undead, Ben symbolizes how becoming a vampire does not have to be as depressing as one would expect. His intelligence is evident in his attempt to draw Robert out of his hiding place, repeatedly yelling "Come out, Neville!" (8) and he later displays a sense of humor when he jumps back and forth over running water, taunting both Robert and the audience with his immunity to one of the apparent weaknesses of the bloodsucker (54). Robert outright remarks that "Ben, at least, had some imagination. For some reason, his brain hadn't weakened like the others'" (108), but Matheson is actually using sarcasm to hint at the protagonist's mistaken assumption that all of the undead are inherently stupid and Ben is the exception. On a wider scale, the author is criticizing Homo sapiens' tendency to degrade, dehumanize, and demonize the other in order to maintain a false sense of superiority, rather than trying to understand the other. Robert ironically postulates that "...that Ben Cortman was born to be dead" (108), which mirrors an earlier comment that Ben Cortman seemed more alive fooling around as a vampire than while he was working at their mundane factory job. This is where Matheson expands upon the idea that there is still an underlying human being within the corpse, arguing that being undead can in fact be a liberation from the monotony of human life. Being zombified is not necessarily the end for everyone, but a new beginning and no one better encapsulates this proposition than Ruth.

Like Virginia, Ruth's name, meaning "compassionate friend" or "vision of beauty" in Hebrew, initially makes her a welcome surprise to the last man on earth. Virginia and Ben Cortman signify the person within the vampire, and Ruth shows that the person and the vampire can coexist on an internal and interpersonal dimension. Like Robert, she is mourning the death of her spouse and her children. Like Virginia, she is kind, empathetic, and inspires feelings of affection within Robert. On top of that, when she confesses to being a spy, she goes out of her own way to warn him to leave the house before the new vampires come after him. The only difference between the Nevilles and Ruth is that they are humans and she is a vampire, thus proving that the differences between the undead and the living are actually non-existent. However, it is crucial to realize that these survivors are far from innocent, including Ruth. For example, the only difference between Ben Cortman and Ruth is that she is slightly more humane and unenthusiastic about killing Robert, giving him a suicide pill so he does not have to be tortured in a show execution after he is captured. This is why Matheson portrays Ben Cortman's attempted escape from the new vampires and his subsequent murder in such an agonizing manner. Although Cortman is no saint, Robert cannot help but urge what is left of his neighbor to run faster and shed tears when he loses the fight for his semi-life. The new vampires are just as prejudiced, just as paranoid, and at just as much fault as their human enemies because they were human.

The two wides of this fictional conflict do deserve some credit in that their biases are at least justified. The new vampires and Ruth fear Robert because he has been ruthlessly killing and experimenting on them. Robert fears the vampires because most of the undead that he has encountered want to drink his blood. The only flaw in Matheson's allegory is that many of the -isms that we have cultivated in the real world are completely ungrounded, and the minority are so marginalized and disadvantaged that they cannot fight back against the majority. Other than that, he does an expert job of illustrating what happens when the majority loathes and attacks the minority. The minority hates and fears the majority because of the threat that the majority poses to them, the minority theoretically overtakes their oppressors and becomes the new majority. Then the cycle continues.

Though I Am Legend predates the use of the word “zombie” by 24 years, its impact on the zombie apocalypse is undeniable. It features many staples of the genre that are more relevant than ever, such as a viral plague, straining to retain one’s sanity in isolation, and societal collapse. It teaches us that true horror stems not from the monster stalking around outside, but from the monster waiting within each and every one of us.

Works Cited

Matheson, Richard. I Am Legend. New York, RXR, Inc, July 1995.

TV Tropes. “Zombie Apocalypse.” Accessed June 9th, 2022. https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/ZombieApocalypse

TV Tropes. “I Am Legend (Literature).” Accessed June 9th, 2022. https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Literature/IAmLegend

Wikipedia. “Uncanny valley.” Last revised June 9th, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncanny_valley

Wikipedia. "Virginia (given name)." Last revised March 25th, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia_(given_name)#:~:text=Virginia%20is%20a%20Germanic%20and,order%20to%20save%20her%20from

Wikipedia. “Zombie.” Last revised June 2nd, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zombie#:~:text=In%20Haitian%20folklore%2C%20a%20z ombie,in%20that%20faith's%20formal%20practices.

About the Creator

Phoebe Sunny Sheng

I'm a mad scientist - I mean, teen film critic and author who enjoys experimenting with multiple genres. If a vial of villains, a pinch of psychology, and a sprinkle of social commentary sound like your cup of tea, give me a shot.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.