Why Joining a Startup May Not Be a Good Idea Financially

And why startups are still amazing

You are a software engineer, probably making $500k a year already. Startups, from large to small, are trying to poach you to join them. Before you decide to make a move, I would like to help you understand the financial impact of joining a startup, so you can make an informed decision.

If you believe in the company and wish you may hit a Jackpot later, I can tell you - The likelihood of a startup having a successful exit is extremely low — around 10%. 90% of the time the employees may not see 1 dime of their equity. The likelihood for you as the Xth employee to have significant financial gain at a successful exit event is also extremely low.

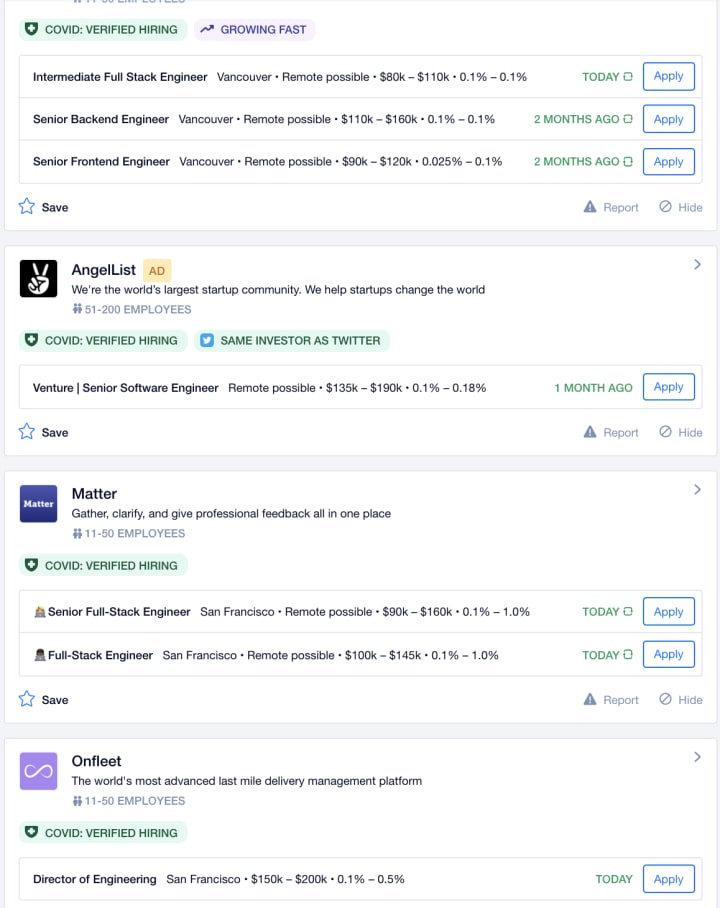

Let me walk you through a real-life example and explain the numbers for you. Here is a screenshot of a job search on AngelList -

You may notice a trend here — the more percentage of the equity the job offers, the more discounted the salary is. It makes sense, right? The company offers more shares to you, and you will get less salary in return.

Does the 5% equity here mean I would own 5% of the company?

The answer is yes, momentarily.

When you receive the offer, 5% will never show up on your offer letter or the Stock Purchase Agreement. Instead, what you will see is the exact number of shares that will be granted to you over a time-based vesting schedule (usually 4 years). The number of shares divided by the total shares that the company has issued should be the percentage — 5%. So, when you receive the offer letter, you should first ask the employer, “What is the total number of the shares the company has issued?” Then you can do the math yourself, to confirm whether you will be granted enough shares.

When you receive the offer letter, you should first ask the employer, “What is the total number of shares the company has issued?” Then you can do the math yourself, to confirm whether you will be granted enough shares.

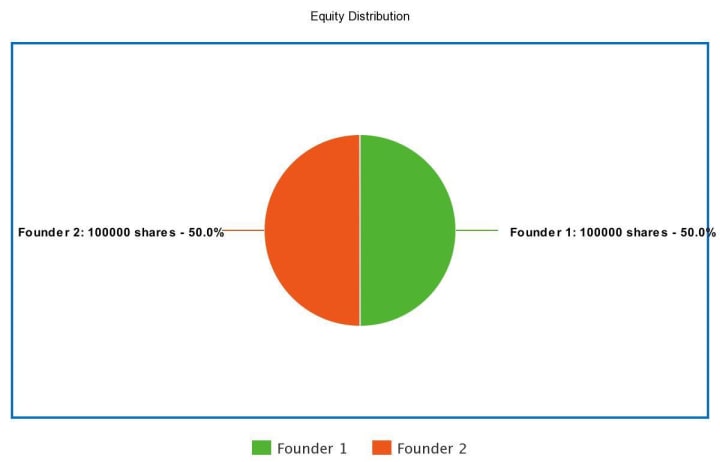

Before you join as an early employee, the equity distribution may look like this —

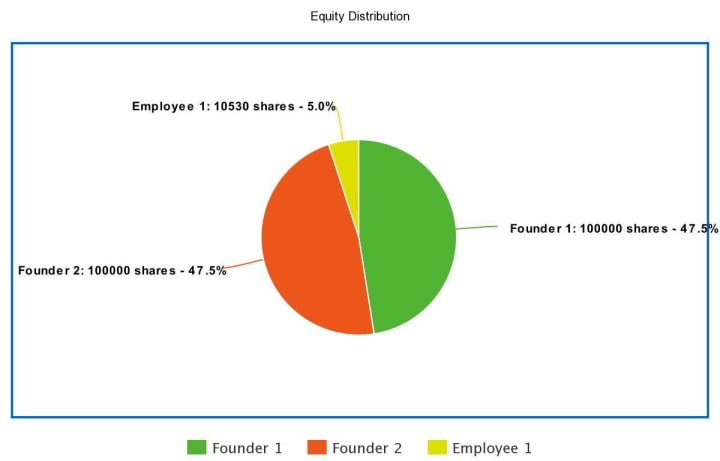

After the 1st employee joins with 5% of equity, the distribution may look like this —

As shown above, the total numbers of shares have not changed for founders, but the percentages decrease to 47.5%.

Years ago, one of my friends in Silicon Valley told me a startup founder offered her a co-founder position with a minimum salary but 20% equity. When she received the offer letter, it only said a number of shares. She had a difficult time making sense of the numbers. I suggested her to ask her potential co-founder how many shares had issued in total. She would take a huge pay cut for this new job, and this was absolutely her right to know how her shares were calculated.

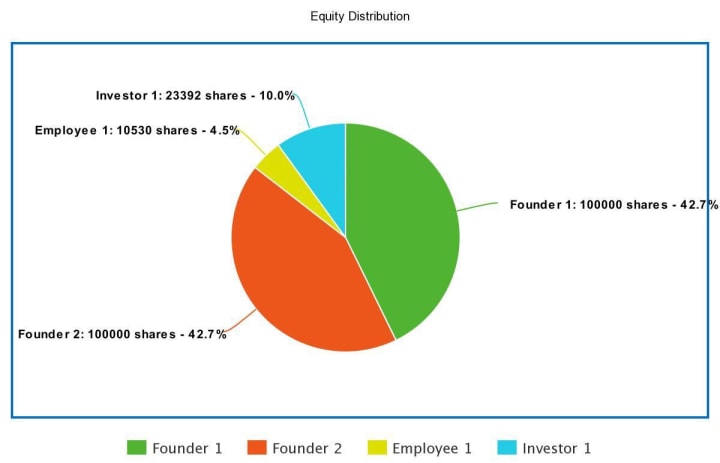

Why is this percentage momentary? Your shares will be diluted by the next funding round. Dilution means that the company issues more shares, which causes your share of the company to shrink. When the company is raising money, it will issue more shares to the new investors. The denominator, the total number of shares, is increasing and your share of the pie is smaller, like this -

With Investor 1 coming in for 10% of the equity, Employee 1’s share goes down to 4.5%.

Corporate attorneys often suggest setting aside a portion of the shares for employees, which is called Employee Equity Pool, usually 10%. Otherwise, as soon as the 2nd employee joins, the shares of the 1st employee are diluted. So it is important for you to ask whether this company has set aside for the Employee Equity Pool. Otherwise, you will likely get diluted as soon as another person joins.

It is important for you to ask whether this company has set aside for Employee Equity Pool.

So, now you know, the advertised 1%, 2.5%, or 5% equity on the job postings will shrink over time.

If the company gets acquired for $1 billion, how much would I get?

You probably have heard the news like a startup got acquired by a big company for a big load of money. You may speculate, your friend, as the 9th employee of the acquired company, probably gets paid with a pile of cash as a result. However, the amount may not be as much as you have imagined.

When a company gets acquired, which is a liquidation event, the fund will be distributed by liquidation preferences (an order to distribute the payout).

When the startup raised money in the past, each investment may be a different investment instrument, some of them are debt instruments, such as SAFE (Simple Agreement for Future Equity) and Convertible Notes, while others are equity instruments, such as Preferred Stock and Common Stock. The payout seniority order goes as follows -

- Debt

- Preferred Stock

- Common Stock

As a principle, debt eats equity. What I mean by that is that for most systems, when the rules of the game are followed, debts have to be paid above all else so that when one has “equity” ownership — e.g., in one’s investment portfolio or in one’s house — and one can’t service the debt, the asset will be sold or taken away. In other words, the creditor will get paid ahead of the owner of the asset.

— Ray Dalio, The Changing World Order

As a startup employee, which type of instrument is your stock? Same as the founders, you have the Common Stock, which is the last to get paid.

A good example is Zoox’s acquisition by Amazon. The acquisition price was nearly $1.2 billion. According to Crunchbase, Zoox raised $955 million, a combination of debt and equity instruments. Debt would be paid first. The investors who hold the Preferred Stock might get a 1-2x return. Some investors may also hold Common Stock and will join the party to slice the rest of the pie, only if there is anything left. In this case of Zoox, I doubt the Zoox founders and employees got anything because the acquisition price was barely 1x of the raised money.

In other cases where there is still some money left for Common Stockholders, depending on how the acquisition deal is structured, founders may have a package of cash and equity of the acquiring company, but the employees may just get the equity vested over 4 years. You basically continue to work for the new company to redeem your slice of the equity.

In contrast, Ring raised $209 million in total before being acquired by Amazon for more than $1 billion, which was almost a 5x exit. In this case, employees could have had a considerable payout if they did have equity.

Now you know, not every big $$$ acquisition is glorious.

Expectations on IPOs

Another celebrated exit for a startup is an IPO. No matter what percentage of shares you have left now, you can finally have the chance to cash out.

However, when the company’s IPO hits Wall Street, Wall Street is very critical about the company's performance, not like the early investors who wholeheartedly believed in the company. There is a chance that the share price could go south once they can be publicly traded.

When Uber went IPO at the price of $45, there was a 6-month lock-up period, during which employees could not trade their shares. After the lock-up period, the price went down to $27. However, the Uber employees were taxed on the RSUs at the price of $45, which had surprised the early Uber employees with a huge tax bill.

Now you know, even after the company goes public, you may not get paid as expected.

So who will work for startups then?

I will not end this article here. Startups are not for everyone but do have their own charm. If the talents really care about money, they may not be the ones startups are looking for.

“Zero to One”

From One to Two is easy, from Nothing to Something is so hard.

Together with the founders, you are onto a path that no one has explored before. No runbook. No manual. Your mistakes and learnings become the 1st draft of the runbook.

In the earlier days at Roxy, we always felt like pushing a big machine forward. A little momentum Roxy gained was worth celebrating because it, was, just, so, hard. When we signed the deal with our first customer, a hotel in Portland, Oregon. When we shipped Roxy devices to the customer. When we signed with the first big customer, a 5-star hotel in Orlando, Florida.

Wearing Many Hats

At a startup, you may not just be the backend software engineer who works on 1 or 2 services. You are someone who works on front-end, back-end, mobile, firmware, and many other IT responsibilities.

At Roxy, not only the founder, I was the full-stack software engineer, hardware engineer, assembly worker, and more.

Do What Matters

At startups, the circumstances have trained you to always ask critical questions and search for objective answers, even the ones that may not sound good or make others happy.

At startups, the resource is limited — limited time, limited headcount, limited cash. You are forced to be resourceful. You do only what produces value.

Being Part of the Journey

The startup journey is something that cannot be bought. Every moment of founding Roxy is precious to me. It taught me to be authentic and honest, always be curious and think critically, be bold, and take risks.

About the Creator

Grace Huang

Co-founder and CTO of Roxy. Ex-Amazon. Entrepreneur. Software Architect. Exotic plant collector. Skateboarding enthusiast.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.