Tintin and the White Man's Burden

Looking back on the Boy Reporter's controversial African adventure

Tintin is going to the Congo, the jewel of the Belgian colonial empire. The reader is given no insight into what the reporter’s actual assignment is besides simply ‘reporting’, positioning Tintin in his early adventures as more of a travel guide than a journalist. Snowy, incorrigible as ever, runs amok on the cruise ship, crossing a shifty stowaway who tries unsuccessfully to drown the poorly-behaved pooch. When they arrive in the Congo, Tintin is greeted as a less of a celebrity and more of a hero when he arrives in the Congo, though his exploits in Africa seem mostly-confined to killing animals, and throughout the story Tintin is shown trying to shoot lions, crocodiles, antelopes, monkeys and elephants--though, usually, not without some comedic mishaps. He soon runs afoul of the local tribes’ Witch Doctor, who is jealous of the reporter’s influence and joins with the aforementioned stowaway, who has his own, unexplained vendetta against Tintin, but their collaborative efforts to dispose of him fail each time. Eventually, Tintin discovers that the stowaway is actually an agent of Chicago mob boss Al Capone, who is attempting a takeover of the African national diamond production, and erroneously believed that Tintin had been sent to expose his plans. The smuggling ring is promptly arrested and Tintin is picked up in a plane, all set to cover the new story developing in Chicago.

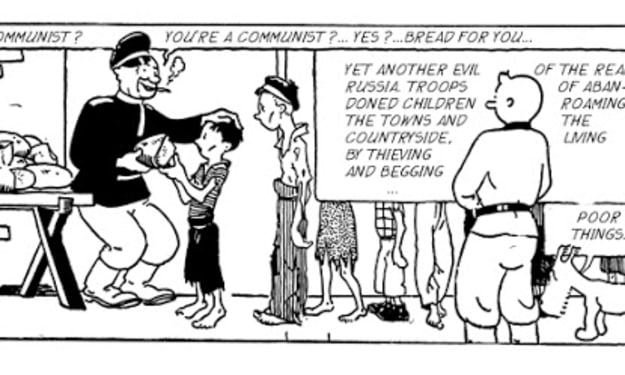

Tintin in the Congo first appeared serialised in the pages of Le Petit Vingtième, children’s supplement of Le Vingtième Siècle, from the 5th of June, 1930, concluding on the 11th of June the following year. had originally wanted to balance his critique of Communist Russia in Land of the Soviets by sending Tintin to the United States next and exploring America’s culture of capitalism and gangsterism However, it was once again Norbert Wallez, editor of the Le Vingtième Siècle and thus ostensibly Hergé’s boss, that chose the reporter’s next adventure; as with Land of the Soviets, it would be in service of Le Vingtieme--and its editor’s--conservative, nationalist political ideology.

The misleadingly-named Congo Free State had been gifted to Belgian King Leopold II by the great European powers in 1885, as part of the wider colonial pursuit dubbed the “scramble for Africa”. This was granted under the condition of allowing free trade of the country's natural resources, particularly rubber, and the typical ideological justifications of Christianisation and humanitarian guidance. Leopold’s pursuit of rubber in the Congo Free State is often regarded as one the most brutal chapters of European colonial history, with rampant stories of the mass murder, enslavement and mutilation of the Congolese eventually leading the Belgian government to take over administration from the King 1908, opting instead for a colonial relationship more typical of European powers at the time.

Wallez was contacted by the Belgian Minister for Colonies in 1930, who informed the editor of the general lack of enthusiasm for the colonial administration amongst the general public. Thus Tintin in the Congo was born from Wallez's desire to both justify and promote Belgium’s colonial presence in Africa, and Hergé set about researching another nation he had never been to.

Despite this premise, the political message is less ham-fisted than it was in Land of the Soviets, and in its second installment, the series begins to read more as more than just nationalist propaganda. The plot is still paper-thin, with no overarching story besides Tintin evading wild animals and outsmarting his assailant, but the inclusion of the stowaway as a recurring antagonist in the story’s first segment does suggest an element of foreshadowing absent in its predecessor. Similarly, by only revealing the character’s identity at the story’s conclusion, Hergé simultaneously adds an element of mystery and sets up his next adventure, which suggests that the author is beginning to think further than just his next panel.

However, as with its predecessor, large sections of the story still read as simple visual gags, and you can tell Hergé had a lot of fun thinking about the misadventures Tintin could get up to while shooting every living thing in sight. Tintin continues to seek cartoonish solutions to his problems, which include skinning a monkey with a pocket knife to disguise himself, creating an enormous slingshot out of rubber cut from two trees, and defeating a leopard by feeding it a sponge and making it drink. Graciously, the scene in which he hunts a rhinoceros by drilling a hole in its hide and dropping dynamite inside has been removed from recent editions.

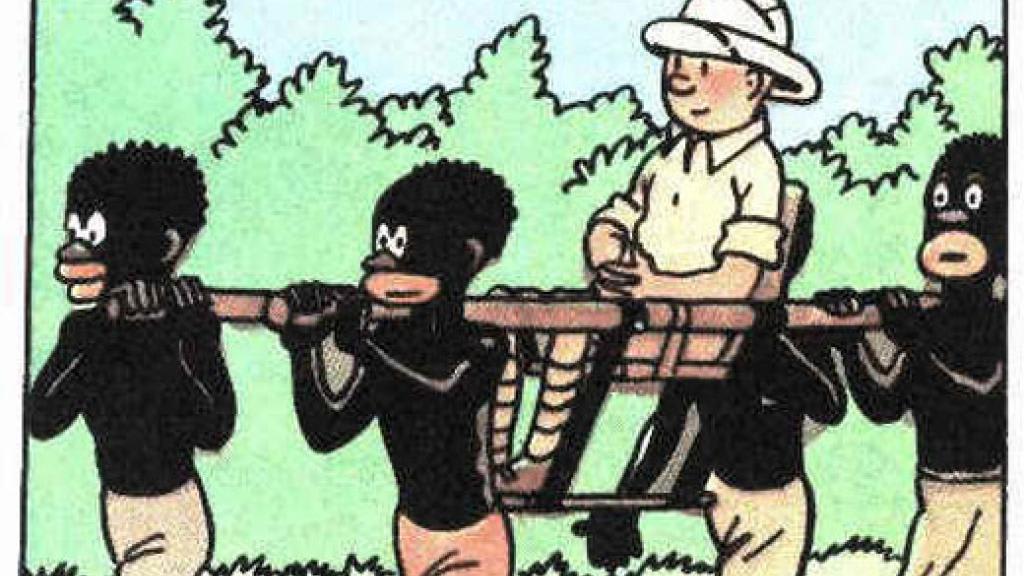

Today, however, the story isn’t remembered for its lighthearted animal cruelty but for its controversial depiction of the native Congolese, and Tintin in the Congo continues to raise questions about racism and censorship. From a modern perspective, it raises more than a few eyebrows. The Congolese are almost like people from a fairytale; from their childlike-simplemindedness to their jet-black skin and huge red mouths and their eclectic bizarre blend of both native-Arican and European fashion, they are reminiscent of Florence Kate Upton’s Golliwogs, which themselves drew the upon the aesthetic of blackface minstrel entertainers.

In accordance for the political purposes for which the story was commissioned, Tintin’s interactions with the natives reflects the belief of the ‘White Man’s Burden’, the ideology that underpinned the European colonial project which posited that Europeans had a moral responsibility to help the cultural, religious and technological advancement of indigenous peoples around the world--a theory that conveniently ignores the many benefits European states stood to gain by conducting such projects, notably an abundance of natural resources and new markets for consumer goods. True to this fashion, Tintin busies himself by assisting the natives whenever possible, nonchalantly demonstrating the positive changes strong-willed European men like himself can make in the lives of these charming but simple people, without once acknowledging the rewards his countrymen would continue to wreap. Compared to Land of the Soviets, the messaging is actually very subtle, but any discerning reader would conclude that Tintin in the Congo is colonial propaganda first and foremost.

Hergé would express embarrassment at his depiction of the Congolese later in life. Speaking about the messaging of his earliest stories in 1975, he said:

"... the fact was that I was fed on the prejudices of the bourgeois society in which I moved ... It was 1930. I only knew things about these countries that people said at the time: 'Africans were great big children ... Thank goodness for them that we were there!' Etc. And I portrayed these Africans according to such criteria, in the purely paternalistic spirit which existed then in Belgium."

There is, of course, merit to this explanation, and it’s worth acknowledging that Hergé’s story is not particularly racist in the context in which it was written; the Congolese depicted are simple, but not savage or contemptible, and Tintin’s approach is one of paternalist guidance rather than hostility. Written at a time of a rising belief in fascist-nationalism and eugenics, this is far from the most-extreme example of racist ideology disseminating at the time.

On the other hand, just because your racism is paternalistic rather than hateful, it doesn’t mean it isn’t racist. Additionally, while much more extreme theories of race-relations were being disseminated at the time, so too were progressive ideas of egalitarianism, human rights and anti-colonialism, but, as Hergé himself admits, these theories did not readily appear inside his social and intellectual domain and were thus not reflected in his stories.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, there have been a number of revisions to this story since it was first serialised 1930. The redrawn and coloured 1946 edition saw the subject of Tintin’s lesson to the Congolese children change from “your country, Belgium” to simple mathematics--perhaps a reflection of Hergé’s changing cultural attitudes at a time when the Congo was still a Belgian colony. This edition also added Detectives Thompson and Thomson to the first panel in an unnamed cameo, retroactively marking their first canonical appearance in the series. The 1975 edition also saw the infamous rhinoceros scene, though all other instances of animal slaughter remain mostly unchanged. Furthermore, in one of these later editions, the decision was made to drop all explicit references to the ‘Congo’ so that in the current version, Tintin simply travels to ‘Africa’, though the title Tintin in the Congo remains.

Owing to the story’s sensitive nature, it was the last in the series to receive a publication in English, with a facsimile of the 1931 black-and-white hitting shelves sixty years later in 1991, and the 1946 coloured edition coming in 2005, wrapped in a red band that warned of potentially-sensitive content. There have been various campaigns across Europe and the United States in recent years to either ban the publication of the book in Europe or at least mandate that it not be sold in the children’s section. Egmont, current publisher of all English-language Tintin books, ceased publication of the story in late 2014 and it has subsequently been left out of their Adventures of Tintin box sets. It is, however, still available as a hardcover from Casterman, complete with red warning band. Additionally, in 2019, to celebrate the 90th anniversary of Tintin, Mouslinart, the managers of the Hergé estate, made a new digital edition available on their Adventures of Tintin mobile app. This new version keeps the original art of the 1931 original, but updates it with a completely new colouring, depicting the Congolese countryside in more realistic brown and yellow shades. The story is also one of only two from the series not adapted for the 1991 animated television series, along with Land of the Soviets.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.