The Ronin that Sticks Out

A look back at Akira Kurosawa's 'Yojimbo'

This is a transcription of an episode of my Japan On Film podcast.

Yojimbo, one of the all-time classics of not only Japanese cinema, but cinema in general. It’s really hard to overstate just how important Yojimbo was to the world of movies, but first, a little bit of background.

Yojimbo, which is Japanese for bodyguard, was first released in 1961 and was directed by Akira Kurosawa, easily one of the greatest directors in history. I won’t go into too much detail about Kurosawa’s life and background. If you’re interested in learning more about him, Isaac Meyer did an episode devoted to Kurosawa in episode 236 of his excellent History of Japan podcast, and that’s as good a place to start as any. But I will bring up a few interesting facts I learned from that very episode which cast Kurosawa’s work in a new light.

The first is that when Kurosawa was thirteen, his older brother, Heigo, took him to view the destruction caused by the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. When the young Akira tried to look away from the bodies of people and animals, his brother wouldn’t let him, telling him that he shouldn’t look away and should face his fears directly. It’s believed that this had a profound influence on Kurosawa’s work, which is why he never shied away from confronting unpleasant truths in his work.

Another fact is that Kurosawa at one point was interested in becoming an artist and joined the left-wing Proletarian Artists’ League, only to later leave, believing that the proletarian movement was simply putting unfulfilled political ideals directly onto the canvas.

And finally, Kurosawa’s father, Isamu, encouraged his children to consume western entertainment such as movies and theater, even though it was taboo at that time in Japan. Heigo had a keen interest in foreign literature and when Akira lived with him, Heigo would take the future director to theaters where Heigo worked as a benshi or Japanese narrator for foreign films. Under Heigo’s guidance, Kurosawa consumed movies as well as theater and circus performances.

I feel these influences figure strongly into Yojimbo and I’ll come back to them throughout this piece. But first, let’s start with an overview.

The movie is of the chanbara, or samurai genre, and takes place in 1860, during the final years of the Tokugawa Shogunate. In Japanese history, this period is known as the Bakumatsu, which basically translates to the end of the Bakufu, the feudal government of the time, and it lasted from 1853-1867. That puts Yojimbo right in the middle of the period. It was a time of social unrest due to a variety of factors, including a series of earthquakes and the opening of Japan to uncontrolled foreign trade, which brought economic instability, disease, uprisings, and political crises.

Be aware that though I’m not giving a full summary of the plot, I will be discussing some things that can be considered spoilers. So if you haven’t seen Yojimbo and don’t want any spoilers, then I recommend giving it a view and then coming back to listen to this episode.

The main character is a ronin or masterless samurai, and played by the inimitable Toshiro Mifune. The ronin didn’t have the status or power of employed samurai, and so were targets of humiliation and satire. In fact, in the 1600s, they were even forbidden from entering cities as the shogunate believed them to be dangerous.

When the ronin is asked what his name is, he responds Sanjuro Kuwabatake. He then quips that he’s actually closer to forty. We know this means it’s not actually his real name as Sanjuro means thirty-years-old and Kuwabatake means mulberry field, which is what he was looking at when asked his name.

Sanjuro arrives in town and as a sign of how dangerous it is, the first thing he sees is a dog calmly walking by with a severed hand held between its jaws. The first thing he does is go into an izakaya (a type of Japanese restaurant/bar) where the old proprietor, Gonji, tells him he’s better off leaving town and explains the situation.

The town’s mayor and silk merchant, Tazaemon, had been in the pocket of a gang leader named Seibei. But when Seibei decided his son would succeed him, Seibei’s right-hand man, Ushitora, felt spurred and broke away. He aligned himself with Tokuemon, the sake-brewer, and declared the sake-brewer the new mayor, thus beginning the gang war between the two sides.

Sanjuro ignores Gonji’s pleas to leave and instead makes the decision to stay as the town would be better if both sides were dead. He then begins to play the two clans off each other.

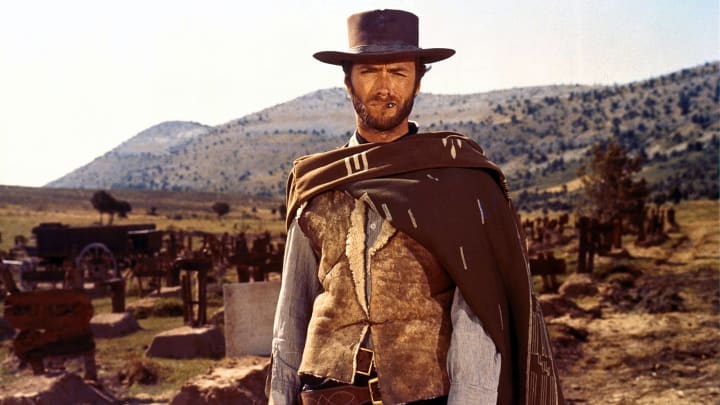

If that plot sounds familiar to you, it’s because it is. It’s the plot of numerous other movies, including but not limited to Brick, Last Man Standing, Django, and most notably of all, A Fistful of Dollars, which turned director Sergio Leone and actor Clint Eastwood into household names.

A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

That’s not by accident, either. I’ll say this next part as a fan of A Fistful of Dollars, it’s one of my favorite westerns. But there’s no way getting around it—it’s a total, almost scene-for-scene rip-off of Yojimbo. In a letter to Leone, Kurosawa said, “I have just had the chance to see your film. It is a very fine film, but it is my film. Since Japan is a signatory of the Berne Convention on international copyright, you must pay me.” Leone didn’t seem to understand the gravity of this letter, as he waved it around, focused more on the fact that Kurosawa called his movie a fine film. A year later, Leone settled out of court, granting Kurosawa 15% of Dollars’ worldwide receipts with a guarantee of about $100,000.

Yojimbo itself wasn’t wholly original either, though. As I mentioned before, Kurosawa had consumed a lot of western media in his youth. He himself acknowledged that a major source for the plot was the 1942 noir film, The Glass Key, an adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s novel of the same name. As other commentators have noted, though, Yojimbo’s plot is far closer to Red Harvest, another Hammett novel. And Red Harvest’s protagonist, the Continental Op, is a “man with no name” character, same as Mifune’s Sanjuro in Yojimbo and Eastwood’s Joe in Dollars.

Kurosawa was also fond of the western genre, particularly the movies of John Ford. The town in Yojimbo may be set in the Japanese countryside, but it at times feels almost like a Japanese town that had been air-dropped into the middle of the Old West.

So it’s more than a little interesting that what we have here is a back-and-forth of cultural influence. Westerns were a huge influence on Kurosawa, and in turn, Kurosawa had a massive influence on the western genre. In fact, by the late 1950s, the western had become stagnant and Hollywood had started gearing down production of them. Leone breathed new life into the genre with Dollars, which would not have been possible if he never ripped off Yojimbo.

Even more interesting than the cross-cultural influence is also some other things I hadn’t noticed before. One of the interesting things that came to me as I rewatched it in preparation of the first time I taught this film in class. In the chanbara films before WW2, the samurai were portrayed much like the cowboys were portrayed in pre-1960s westerns. They were heroic, noble, cookie-cutter good guys. Postwar samurai films depicted them as darker, more violent, cynical, and psychologically scarred, and Kurosawa is a big reason for that.

Yojimbo is also pretty comedic, albeit in a very dark way. I noticed something during the fights between the gangs—they don’t charge at each other in a flail of swords and dramatic combat. Instead, they stand at a near-stalemate at the beginning. One side advances and the other retreats, then vice-versa. And the entire time, all their swords are violently shaking in their hands.

In other words, pretty much every single character in this movie is a coward, with the exception of Sanjuro and Ushitora’s younger brother, the gun-wielding Unosuke. Even Honma, Seibei’s so-called master swordsman, runs off in fear before a battle with Ushitora’s men. Both the gangs are filled with cowards.

One of the things I found the most interesting in the movie was the focus on corruption and how that connects to postwar Japan. For just about the entirety of its postwar history, the conservative Liberal Democratic Party and its two precursors—the Liberal Party and the Japan Democratic Party—has held almost-unbroken rule in the Japanese parliament.

The LDP has a very long history of corruption. For years following the end of the American occupation, the CIA funneled money into the party. Due to Cold War paranoia, America was terrified of Japan’s left-wing elements coming to power, and they made nice with many of the militarists they once imprisoned for war crimes, including Nobusuke Kishi, a noted anti-democratic fascist who believed in a totalitarian Japan and whose grandson, Shinzo Abe, is Japan’s current Prime Minister at the time of this writing.

The CIA not only funded the LDP and its precursors, but also the yakuza, the Japanese mob. LDP politicians and yakuza syndicate members have long been associated with each other, with the LDP using yakuza members to attack political rivals, suppress embarrassing newspaper stories, and fund their campaigns.

The purpose of giving you this little background sketch is that a lot of those parallels can be seen in the relationships between the gangsters in Yojimbo and the town’s politicians. Tazaemon had long been a puppet of Seibei’s, whereas Ushitora backed Tokuemon.

That’s not necessarily intentional, though. Most of the LDP’s corruption wasn’t really public knowledge until the 1970s and their CIA ties weren’t exposed until the mid-90s. So it could just be a fascinating case of life imitating art.

I wanted to take some time to talk more specifically about Toshiro Mifune’s performance. He’s definitely more of the revisionist style of samurai . Though he is honorable to an extent, he’s by no means humble. He’s a bit carefree and very confident. He doesn’t sit properly, but takes a more casual posture. He’s also not at all clean-cut.

Kurosawa told Mifune that Sanjuro was like a dog or a wolf, and that’s why Mifune incorporated many of the mannerisms he uses in his performance. Things like his shoulder twitch or the way he’s always scratching his scruff.

There’s also an interesting insight into his background. We’re told nothing about Sanjuro, but we get one big hint. Throughout pretty much the entire movie, Sanjuro remains cool. There’s one exception, when he meets Kohei and his son, and is told by Gonji that Kohei’s wife, Nui, was taken prisoner by Tokuemon because Kohei couldn’t pay off his gambling debts.

This is when Sanjuro loses his temper, saying that guys like Kohei make him sick. It’s the most emotional we ever see him get. This is what leads Sanjuro to perform completely selflessly and put his own life at risk in order to rescue Nui. He reunites the family and gives them 30 ryo, then tells them to leave. When they express their gratitude, he gets angry and tells them he despises weaklings.

I feel there’s a sense that Sanjuro saw something in this family that reminded him of his past. I imagine he was once like Kohei and Nui’s son and something similar had happened to his mother. That explains Sanjuro’s sudden selflessness and his uncharacteristic emotionality.

What solidified this theory in my mind was when watching A Fistful of Dollars. As I said, it was practically a scene-by-scene rip-off, but there’s one interesting distinction in the reunion scene. The Dollars version of Nui is named Marisol and after Joe rescues him, she actually asks him why he helped. Joe replies that he knew someone like her once and there was no one there to help.

It’s made obvious in Dollars what is only subtly implied through Mifune’s performance. Nonetheless, Mifune manages to give us this impression with his skill as an actor. It’s just one example of how incredible his performance in this movie really is.

The last thing I wanted to mention is both the cinematography and the music. It’s very distinct and you can definitely see the influence both of western genre films that preceded Yojimbo and the influence it in turn had on western films that followed. Kurosawa uses a lot of long shots that really make you feel how isolated this town is and how there’s no one the people can go to for help. And even if they could go to someone for help, the ineffectiveness of the government is showcased in the scene when the bugyo—an Edo-era government official—arrives in town and is called away because Ushitora had assassins kill another official in another town in order to get the bugyo to leave. Essentially, they’re puppets of the criminal element, much like the LDP and the yakuza.

Another interesting aspect is the music. Masaru Sato’s soundtrack was inspired by Henry Mancini, and that happened because Kurosawa told Sato to write whatever he wanted, just as long as it was something different from the typical music used in samurai films. And while Sato uses traditional Japanese instruments, he also mixes in some jazzy elements that give it this very discordant, chaotic feel. The music is as wild and strange as Sanjuro himself.

There’s a famous Japanese proverb—出る釘は打たれる (deru kugi wa utareru). You’ve no doubt heard of the English translation—the nail that sticks out gets hammered down. It’s often used to illustrate the conformity and homogeneity in Japan. And that’s true to an extent, and can certainly be seen in the Japanese public school system. But one of the themes of many of my favorite Japanese movies is the role of the outsider. Sanjuro certainly fits the part of an outsider in that he’s completely unlike anyone else in town and as such is able to change it for the better.

About the Creator

Percival Constantine

An action fiction novelist and a lifelong fan of comics and film. Discover my fiction at percivalconstantine.com.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.