The Reality TV Effect

What Makes Reality Television So Successful?

The Bachelor is a reality television series in which twenty-five single women in one household compete for the love of their life. Everything on The Bachelor is meticulously crafted with the viewer’s judgement in mind. When introducing each bachelorette, the producers make clear which characters they want the audience to feel empathy for or to root against. The moment the show reveals 26-year-old contestant Renee, her elimination becomes inevitable. Whether she is kissing a dog or creating a vision board, the show makes clear that this erratic woman must be eliminated. After being eliminated, she stutters while claiming that her “vision boards are real and a lot of good things come from it’’(“Episode 1”). This example is illustrative of the command producers have over the viewers’ emotions. Of course, Renee is not the only reality TV show contestant to be negatively portrayed by producers. The reality is, casting agents want people like Renee to increase the entertainment value of their shows. Although not all viewers are aware of the manipulation in producing reality television, there is something about the predictability, the judgement, and the absurdity involved with characters like Renee that producers use to intrigue viewers.

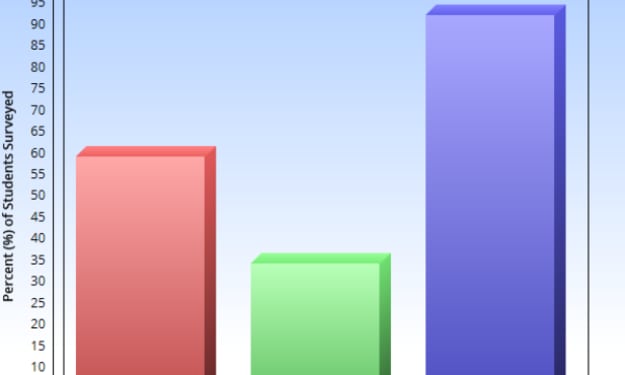

This longing for shows like The Bachelor is perhaps deeply rooted in our conscience. In her eleven-minute TED Talk, TV executive Lauren Zalaznick reveals graphs correlating cultural events with the type of television we watch. One such graph depicts the popularity of humor versus judgement television shows from 1995 to 2009. In September 2001, the popularity of judgement TV shows surpassed that of humor TV shows. Zalaznick notes that around this time, the nation experienced 9/11, the tech bubble burst, and the 2000 election decided by the Supreme Court. Lauren Zalaznick believes that television reflects “the moral, political, social and emotional need states of our nation’’(Zalaznick 2). When we lose control over our lives, we want to regain authority. We no longer feel the need for lighthearted television; rather, we invest our time in shows where we can either assert our authority over a contestant or feel moral superiority over them. Shows like American Idol allow viewers to vote for a contestant they relate to, and laugh at the ones who look or act ridiculous.

It is also paradoxical predictability and voyeurism that contributes to reality television's appeal. The viewer often has a premonition about what they are about to witness, but they continue watching. In Don DeLillo’s short story titled ‘’Videotape’’, he provides an explanation for this. He claims that people ‘’keep looking because things combine to hold you fast---a sense of the random, the amateurish, the accidental, the impending [...] It is crude, it is blunt, it is relentless’’(DeLillo 1). This feeling of spontaneity feeds a reptilian desire in us as viewers. We want to see raw footage of arguments and breakdowns. We feel as if we are peering into someone’s life and watching them suffer. In the Bachelor, we get a view into a living room conversation between Renee and the bachelor. Renee starts to speak about her vision boards, and we laugh as the bachelor’s expression morphs from one of comfort to one of horror. We are there in the living room, yet removed enough to ridicule the contestant.

However, the truth is that reality television is ironically not always real. Producers are aware of what makes their shows so intriguing, so they try to orchestrate as much conflict and drama as possible. The emotional conversations between Khloe and Kim Kardashian may be scripted, yet millions of fans still tune in to watch every new season. How can shows like Keeping Up With The Kardashians be so artificial yet capture such a large audience? Plato’s allegory of the cave involves men chained in a cave, forced to watch shadows on the wall in which they believe to be real. One day, one man is unchained and allowed to explore the real world. When he returns to the cave, he tries to set the other men free, but they are too stubborn. In his allegory, one character states ‘‘How could they see anything but the shadows if they were never allowed to move their heads?’’(Plato 253). The shadows on the wall can be likened to participants who appear in reality TV shows. We as an audience, are perhaps too stubborn to turn our heads away from the shadows because we perceive it to be reality. So long as shows maintain their image of reality, our voyeurism is not destroyed. Television producers may go extreme lengths to secure this realistic image, using footage that seems privacy-invading or untampered with. When television consists of only these clips, it is possible to lose context. Audiences have to make judgements with the little information they are given. Instead of viewing characters with depth, the audience is left to watch shadows manufactured by producers to elicit a specific emotional response.

Popular television has and will continue to reflect our national conscience. What kind of conscience are we reflecting if we watch humiliated contestants suffering at the expense of ratings-hungry producers? Perhaps we are mirroring a shallow nation with a desire for control and manipulation. When watching television, we become as flat as the characters on screen; we are just as predictable and controllable as the shadows on the wall. If we are watching for control or judgement, we should realise that the characters portrayed on screen have little control over the image we criticize. In trying to escape the crises of our nation for control and power, we consequently are becoming manipulated like the contestants on television. Although it is easy to fall victim to our reptilian desire, we as a nation have evolved past that. Perhaps it is time to unchain ourselves from these cave walls and step outside into reality. There, we will find people and places with depth and charisma instead of merely manufactured shadows on a wall.

Works Cited

DeLillo, Don. Videotape. 1994.

“Episode 1.” The Bachelor, season 13, episode 1, Jan. 2009.

Plato. “The Allegory of the Cave.” The Republic, Plato, 38n.d., pp. 253–261.

Zalaznick, Lauren. “Transcript of ‘The Conscience of Television.’” TED, TED Women, Dec. 2010, www.ted.com/talks/lauren_zalaznick_the_conscience_of_television/transcript?language=en.

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.