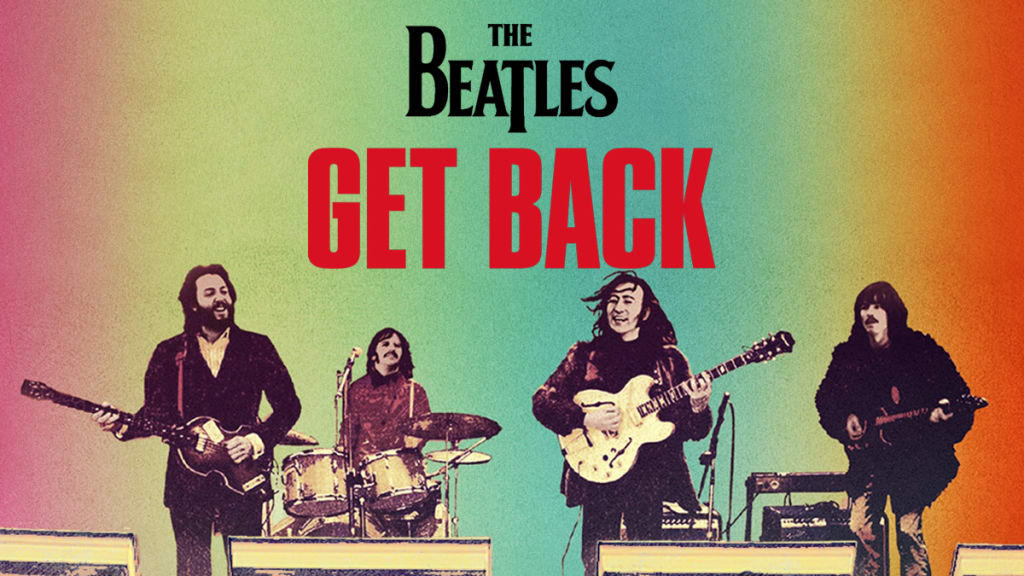

The Beatles: Get Back and the Magic of the Extended Blooper Reel

Can imperfection serve as a demystifying force?

A few weeks ago, my boyfriend, noted hater of horror movies, remarked, "I think I'd find them more watchable if they included a blooper reel at the end." I found this to be an odd statement, but when I probed him on it, he said that the reason a blooper reel would de-horrify a horror movie is because it would “strip away the illusion.” Seeing actors fudge lines, trip over set pieces, and crack up laughing would make the polished, disturbing stuff seem less real. “But we don't need a blooper reel to know it's not real,” I told him. “We already know that.”

Yet while it's one thing to know something, it's something else entirely to be constantly reminded of it. Before watching Peter Jackson's The Beatles: Get Back, I knew just about all there was to know about the Beatles. In high school, I went through a period where I consumed Beatles-related content at an alarming and worrying rate. I watched all their movies multiple times, to the point of being able to quote lines and entire scenes from them on command. I read Anthology and owned a 700-page, full color encyclopedia that detailed the inspiration and recording process for every single song they ever made. I knew all the wacky anecdotes—the time Paul McCartney and Pete Best lit a condom on fire, the time Paul took John to the roof to get some air because he was tripping on LSD in the recording studio, and the time George harshly chastised Yoko for eating one of his digestive biscuits. These stories, as much as I wish I could unlearn some of them, humanized the band for me. When I read about the Beatles acting foolishly or making ordinary, clumsy blunders, for a moment, they wouldn't seem like unattainable musical gods but like people I could presumably meet on the street.

I knew, consciously, that the Beatles were not gods, but the illusion was so powerful that I required frequent reminding. And though I chastised my boyfriend for needing a blooper reel for a horror movie to seem less real, what I'd been doing in my memorization of unsavory, un-godlike Beatles anecdotes had essentially amounted to that same exact thing: creating my own mini blooper reel of the band. And that's where I think Get Back succeeds—not as a documentary, but as an eight-hour-long blooper reel.

Critics of the documentary have called it bloated or lamented being forced to sit through hours of unpolished studio screwery. “There is a point, about five hours in,” Alexis Petridis of The Guardian remarks, “when the prospect of hearing another ramshackle version of Don’t Let Me Down becomes an active threat to the viewer’s sanity.” But I had the opposite reaction. Watching the songs transform from shabby to polished in front of my eyes was part of the magic. When Paul sang the first two lines of the “Jojo” verse of “Get Back” over and over again in many variations, trying to get the syllables to match the melody, I found myself almost infuriated. I kept singing the correct line at the TV, as if hoping my voice would traverse time and space and convince 1969 Paul McCartney that this was the way to make it work, because he'd already done it. And it's true—2021 Paul McCartney had already done it, but 1969 Paul McCartney had not. Still, he got there eventually, and when he did, it was immensely satisfying.

That's the illusion of the finished product—the idea that it's always been that way. In movies, it's the subconscious assumption that actors are simply reacting to their surroundings in real time, as opposed to performing a rehearsed scene. In music, it's the impression that the piece must have occurred to the artist in a burst of inspiration and flooded out of him, fully formed, in a possessed eruption of genius. This phenomenon is what's being described when people use the phrase, “You make it seem so easy.” What they're really saying is, “You make me forget about the reality of the creative process.” But it rarely is easy—yes, even for "legends." When you listen to a song or read a book or view a piece of visual art that inspires you to the point of thinking, “How on earth could anyone come up with this?” the answer is probably that it took concerted effort. It was worked and reworked several times. It was the result of a long and wrought process.

This all may seem mind-numbingly obvious, but you'd be surprised by how often people like to obscure the reality of the creative process in favor of myth, and Beatles fans are particularly notorious for this tendency—why do you think the anecdote about Paul McCartney composing the melody of “Yesterday” in a dream is such a popular one to throw around? It's a rare case of something being truly inspired. But let me ask you this: would “Yesterday” be any worse of a song if Paul had spent hours crafting that melody? Would the finished product be any less enjoyable?

There's a moment in the rooftop concert, during the group's second rendition of “Don't Let Me Down,” that John completely fudges the lyrics, singing a line of unintelligible gibberish. This rendition used to be available on YouTube, but at some point, it was taken down, and I had hoped Peter Jackson would include it in the documentary. I'm happy he did. I always wondered why the version of it on YouTube was removed—was it to maintain the impression in people's minds that John Lennon was not capable of making mistakes? Did whoever removed it worry that showing the Beatles making a flub would somehow threaten their status as the Greatest Band in History?

Maybe I'm overthinking this, and I probably am, but I realize, now more than ever, that the Beatles were not as good as they were because they didn't make mistakes but because they did. The iconic sustained note at the start of "I Feel Fine" is the result of George Harrison accidentally leaning too close to a speaker and creating feedback (Guesdon and Margotin 200). The perfectly timed ring in the background of “A Day in the Life” before Paul sings, "Woke up" was the result of an alarm clock coincidentally going off while they were recording (Ibid 405). The Beatles have always reveled in mistakes, regarded them as opportunities. When John Lennon's rooftop blunder was played back to him after the concert, he didn't shy away from it. He looked straight at the camera, proudly, and nodded.

The most destructive byproduct that has resulted from the mass cultural perception of the Beatles’ infallibility is the myth that it was Yoko Ono who destroyed the band—that the Beatles were too legendary to crumble from within and thus needed an outside force. I used to consider myself enlightened in that regard. When people would claim she broke up the Beatles, I would respond that she was just one of many factors. However, after watching Get Back, I think we can pretty much absolve Yoko of any responsibility whatsoever. Not only was she wholly unobtrusive during recording sessions, but the other three Beatles didn't seem to mind that she was there. At one point, Paul even defended her presence. Perhaps Get Back won't be enough to convince those who wish to blame Yoko for the breakup no matter what—perhaps they'll claim that all the footage of Yoko acting out has been conveniently edited out—but there's probably nothing that could change those people's minds anyway.

I almost wish Get Back could have been released seven years earlier. I wish the girl who drove an hour to see the A Hard Day's Night fiftieth anniversary re-release in theaters—A Hard Day's Night, the movie I owned on DVD and had watched a dozen times—could be the one to experience hours of previously unreleased full-color studio footage of her favorite band. But, as much as it feels sacrilegious, I almost enjoyed Get Back more than A Hard Day's Night. In A Hard Day's Night, the Beatles were playing the pre-iconographic, exaggerated, character versions of themselves. The purpose of the movie was to reinforce the myth—to further expand the aura of godliness that followed them everywhere in the form of hordes of screaming girls. Over fifty years of cultural cementing and hundreds of biographies (many of which claim to “dispel the myth”) later, the illusion of godliness has remained firmly intact. Maybe now, with Peter Jackson leading the charge, we can finally begin to strip it away.

Works Cited

Guesdon, Jean-Michel, and Philippe Margotin. All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Beatles Release. Edited by Scott Freiman, Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2013.

Jackson, Peter, director. The Beatles: Get Back, Disney+, 25 Nov. 2021.

Petridis, Alexis. “The Beatles: Get Back Review – Eight Hours of TV so Aimless It Threatens Your Sanity.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 25 Nov. 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2021/nov/25/the-beatles-get-back-review-peter-jackson-eight-hours-of-tv-so-aimless-it-threatens-your-sanity?utm_term=Autofeed&CMP=twt_gu&utm_medium&utm_source=Twitter#Echobox=1637832117.

About the Creator

Hannah Smart

Middlebury College class of 2019. Amateur musician and writer.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.