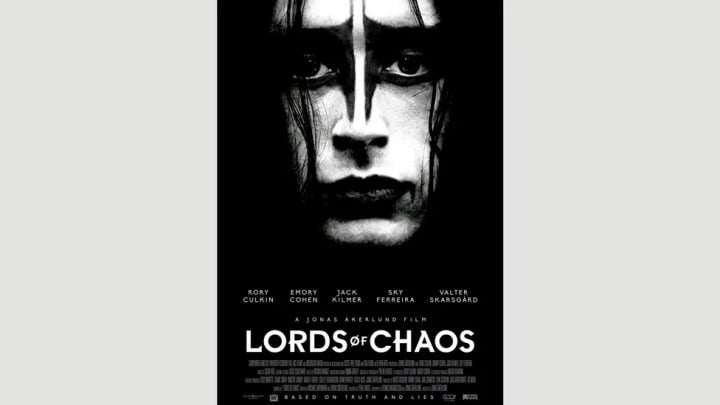

Lords of Chaos: The grisly film that has caused outrage

A new movie tells the appalling true story of Norway’s ‘black metal murders’.

Jonas Akerlund’s new film, Lords of Chaos, is a rock’n’roll biopic, with all the wigs and gigs that that implies. But it is also a grisly, stranger-than-fiction comedy drama about murder, suicide, self-harm, devil worship, and a spate of arson attacks that scandalised a nation. Chronicling the outrageous crimes committed by a few Norwegian black metal bands and their hangers-on in the early 1990s, the film probably won’t appeal to lovers of Bohemian Rhapsody – and there have even been calls from some church groups for the film to be banned.

The story behind it begins not in Norway but in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in England, where a heavy-metal trio called Venom recorded its second album, Black Metal, in 1982. Before that, popular music had a long history of flirting with satanic imagery, from Robert Johnson’s Hellhound on my Trail to the Rolling Stones’ Sympathy for the Devil to the provocatively named Judas Priest and Black Sabbath. But Venom took this unholy relationship further. “It’s hard to explain to younger people just how shocking Venom were back in the early ’80s,” says Chris Kee, a journalist for the magazines Zero Tolerance and Powerplay. “Satan appeared on the album covers and was namechecked in pretty much all the songs. This was blatant pledging allegiance to the dark lord. I remember looking at the burning crucifix in the gatefold sleeve of their 1984 album, At War With Satan, and wondering if this really was a step too far.”

Venom’s Black Metal album became the foundation stone of a whole new sub-genre. If you felt that thrash metal was too commercial, and death metal was too breezy, then black metal was the music for you. Nick Ruskell, a senior editor at Kerrang! magazine, defines it as “a harsh, dark form of heavy metal with a focus on extremity and a satanic bent – although if you asked five fans you’d get seven different answers”.

Ohlin wore black-and-white ‘corpse paint’ make-up so that his face resembled a skull

Venom aside, the bands that forged black metal were Scandinavian. From Sweden, there was Bathory, whose drummer happened to be Jonas Åkerlund, the director of Lords of Chaos. From Denmark, there was Mercyful Fate. And in Norway, a younger generation of metal enthusiasts was listening and learning.

One such enthusiast was ystein Aarseth, a guitarist who is played in the film by Rory Culkin. He formed a band called Mayhem, and, just as Venom’s members had given themselves grandly spooky stage names – Cronos, Mantas, Abaddon – Aarseth chose a demonic nom de rock drawn from Greek mythology, Euronymous. Once he had recruited a Swedish singer, Per Yngve Ohlin (stage name: Dead), the band decamped to a house in a forest to live and rehearse. If Aarseth’s gloomy guitar playing was the archetypal sound of Norwegian black metal, it was Ohlin who developed its own brand of showmanship. He wore black-and-white ‘corpse paint’ make-up so that his face resembled a skull, and at Mayhem’s concerts, he would self-harm. But his preoccupation with death wasn’t confined to morbid theatrics. In April 1991, Aarseth returned to their house to find that Ohlin had killed himself.

‘The black circle’

That could have been the end of Norwegian black metal. But Aarseth saw Ohlin’s death as a chance to promote himself as the leader of a truly dangerous and diabolical music scene. Before contacting the police, he went out and bought a disposable camera so that he could photograph Ohlin’s remains. He then set up his own record label, Deathlike Silence Productions, and opened a record shop in Oslo named Helvete (the Norwegian for ‘Hell’). His closest associates, he decreed, would be ‘the black circle’, and they alone would be allowed into black metal’s inner sanctum, ie a damp basement room beneath the shop.

A key member of the black circle was Kristian ‘Varg’ Vikernes, a teenager from Bergen who preferred to be known as Count Grishnackh. He soon built a reputation for doing the things that Aarseth only talked about. While Aarseth was still struggling to finish Mayhem’s debut album, Vikernes recorded several solo albums under the Tolkienesque name of Burzum. And while Aarseth gave interviews about spreading hate and fear, Vikernes started setting fire to Norway’s historic wooden ‘stave churches’. On 6 June 1992, Fantoft Stave Church burnt down. Vikernes called his next EP Aske (Norwegian for ‘ashes’), and put a photograph of the church’s charred shell on the sleeve. Each copy came with a free cigarette lighter. Scandinavia’s black metal fans took the hint, and dozens of other churches went up in smoke. Some had inverted crucifixes and the number 666 spray-painted onto the ruins.

Most of the black metal guys wanted to appear as evil as they could – Kevin Hoffin

Satanism? Maybe, maybe not. Over the years, numerous black-metal musicians have become serious students of the occult, but back in 1992, they cared more about seeming sinister and subversive. “Most of the black-metal guys wanted to appear as evil as they could,” says Kevin Hoffin, the author of TRVE: The Norwegian Black Metal Scene, “hence they promoted Satanism and inversion of biblical tenets. The tabloids had a field day as they’d found a way to carry on the ‘Satanic Music’ moral panic that plagued Judas Priest and Ozzy Osborne in the previous decade. But it was childish, insincere Satanism. The church-burnings, for instance... it’s easy to burn down a church that’s made of wood.”

As for Vikernes, he claimed that the arson was a protest against religions from the Middle East that had replaced his forefathers’ pagan Norse gods. It seems his belief system was closer to fascism than Satanism. And he wasn’t alone. In Aaron Aites and Audrey Ewell’s documentary about Norwegian black metal, Until the Light Takes Us, it’s striking how often the interviewees resort to racist and homophobic rhetoric.

Nor was their homophobia confined to hate speech. In August 1992, another of Aarseth’s friends, Bård Eithun (or ‘Faust’), murdered Magne Andreassen, a gay man who approached him in a park in Lillehammer. Vikernes was so pleased that he boasted to journalists from the Bergens Tidende newspaper that he knew who was responsible for the arson attacks and the murder. A front-page article, We Lit The Fires, ran in January 1993.

Two months later, Britain’s leading heavy-rock magazine, Kerrang!, published a cover story on the same events. It was written by Jason Arnopp, now a script-writer and the author of The Last Days of Jack Sparks. He also appears in Lords of Chaos, playing his younger self. “When I interviewed Euronymous on the phone at the time,” says Arnopp, “he spoke in cold, hushed tones, as if trying to portray himself as a dark, mysterious character. This obsession with image very much comes across in Lords of Chaos: these were teenagers who wanted to control the way the world saw them and gain notoriety.”

They succeeded. The Kerrang! feature ensured that rock fans everywhere would seek out Norwegian black metal, as Ruskell remembers. “I read about them when I was about 12,” he says, “and a music scene where people burnt churches and killed people and wanted to be in league with Satan was genuinely scary. Growing up in a Church of England household, I really wanted to know what these bands sounded like.”

The saga of the so-called ‘black metal murders’ is so appalling that it’s difficult to process, even now

Vikernes’ and Aarseth’s infamy leapt to a horrifying new level in August 1993. Having convinced himself that Aarseth was planning to kill him, Vikernes drove to Aarseth’s Oslo flat in the middle of the night, and murdered him. In May 1994, he was sentenced to 21 years in prison, both for Aarseth’s murder and for multiple church burnings. He was 21. That same month, Mayhem’s debut album was finally released. It included lyrics by Ohlin, guitar-playing by Aarseth, and bass-playing by Vikernes, which made it a grotesque rarity: an album on which one contributor had killed himself, another had been murdered, and another was the murderer.

The saga of the so-called ‘black-metal murders’ is so appalling that it’s difficult to process, even now. Is it linked to the psyche of the country that brought us Edvard Munch and a bookcase of lurid Nordic noir novels? Or does the devil really have all the best tunes? “I don’t think the story is quite as incredible as it first seems,” argues Kee. “If you take a small group of young men, one with obvious mental health problems, one a charismatic leader, all looking to be part of something, and all dissatisfied with life, and then you throw in some occultism, some low-level fame and some internal power struggles... you’ve got Lord of the Flies.”

The most significant factor may not have been Satanism but immaturity. In photos from the early 1990s, the skinny musicians, glowering in their leather jackets and their Halloween make-up, look as if they are copying Kiss and Alice Cooper but don’t have the budget or the sense of humour. They could be auditioning for Spinal Tap: The Next Generation. And as iconoclastic as they professed to be, they went along with the customs of Norwegian society when it suited them. Vikernes’ Burzum recordings were funded by his mother, while Aarseth’s parents bankrolled his record shop.

Åkerlund has described Lords of Chaos as “a movie about idiots”, and “young boys ... doing stupid things”. Arnopp believes that “the whole sorry affair comes down to a combination of peer pressure, small-town teen rivalry, and the urge to rebel against organised religion”. And Hoffin sees the murders and fires as “a macabre competition that got out of hand”.

But as comforting as it might be to write off Aarseth and his coterie as privileged brats who got caught up in ghoulish play-acting and one-upmanship, their crimes were real enough. And, for those who are interested, their records are still available. “It was tragic, too, that these people actually had no shortage of talent,” says Arnopp. “If they really were motivated by the need to draw attention to themselves on the world stage, then their music would eventually have achieved that by merit alone.”

About the Creator

Sue Torres

Is there any other reason to live to change the world?

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.