Last night I went to Manderley again… I wish I hadn’t bothered.

It has been over a month since the release of Ben Wheatley’s take on Daphne du Maurier’s magnum opus, Rebecca. Whilst it is a handsome movie, with some striking visuals, I did feel a little dejected. I have spent the past month revisiting Rebecca, as well as re-watching Hitchcock’s 1940’s adaption, and decided to write a short essay comparing the two adaptations, and explaining why Hitchcock’s adaptation is not only superior, but a more faithful adaptation.

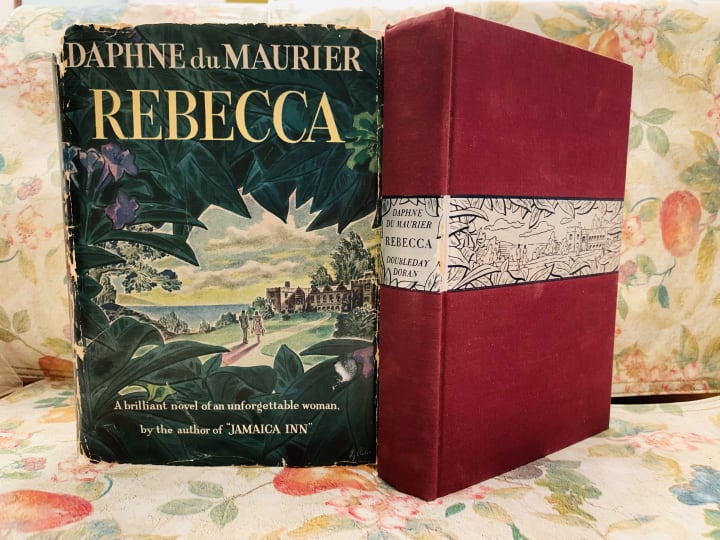

Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca is a novel that continues to haunt and mystify readers eighty years after it was first published.

The story is a simple yet compelling one. It follows a shy, timid young woman, who whilst working abroad as a paid companion to an American socialite, becomes acquainted with a wealthy aristocrat by the name of Maxim de Winter. He is the owner of Manderley, a beautiful mansion in the South-West of England, renowned for its magnificence and extravagant parties. Mr. de Winter is the source of much gossip among the chattering classes as his wife, the eponymous Rebecca, has recently died in a tragic boating accident and he is said to be grieving terribly. After her benefactor falls ill, du Maurier’s nameless narrator is able to develop a budding romance with the older Mr. de Winter. Despite her humble background and his penchant for isolation, the two fall deeply in love and impetuously marry. After a brief honeymoon in Italy, the newly-weds travel to their stately home of Manderley to begin their new life together. Almost immediately upon her arrival, the new Mrs. de Winter feels uncomfortable. This is in part because she is unaccustomed to the aristocratic life, but her apprehensions are only exacerbated by Mrs. Danvers, the subversive housekeeper who, for reasons unknown, seems intent on making the new Mrs. de Winter feel unwelcome in her new home. In addition to this, she is surrounded by ghastly mementos reminding her of the “beautiful, talented” Rebecca, who was “loved by all who knew her.” Indeed, Rebecca purportedly was universally adored. Maxim’s sister and grandmother speak fondly of her. Frank, the dutiful agent of Manderley, and closest thing the new Mrs. de Winter has to a friend, describes her as “the most beautiful creature [he] had ever seen.” It is also revealed that this is the reason Mrs. Danvers is treating her with such hostility, for she had known Rebecca since she was a child. Her feelings for Rebecca go beyond adoration.

Maxim’s behaviour also changes upon his return to Manderley. He becomes aloof and bad-tempered. This increasing distance results in the new Mrs. de Winter becoming increasingly forlorn and isolated. As the story progresses she begins to doubt her new husband’s love, and her own sanity.

Things take a dramatic turn however when the remains of Rebecca's sailing boat, with her decomposed body still on board, is found. This discovery causes Maxim to confess to the narrator that his marriage to Rebecca was a sham. Rebecca, Maxim reveals, was a cruel and selfish woman who manipulated everyone around her into believing her to be the perfect wife and a paragon of virtue. She had numerous affairs, including with his own brother-in-law and her own cousin, a rogue by the name of Jack Favell. Rebecca was capable of great cruelty. When she is caught having an affair by a young, mentally-challenged gardener, she threatens to have him imprisoned at an asylum if he ever tells anyone. Rebecca’s cruellest act came on the night of her death. She taunts Maxim implying that she is pregnant with another man’s child and that she intends to raise it under the pretence that is was Maxim’s. In a rage, Maxim shot her through the heart killing her. He then placed her body on the boat and sunk it. Whilst shocked, the new Mrs. de Winter is relieved to learn that Maxim never loved Rebecca.

Rebecca's boat is raised, and it is discovered to have been deliberately sunk. An inquest brings a verdict of suicide. However, Jack Favell, attempts to blackmail Maxim, claiming to have proof that she could not have intended suicide based on a note she sent to him on the night she died. It is revealed that Rebecca had had an appointment with a doctor in London shortly before her death, presumably to confirm her pregnancy. When the doctor is found, he reveals that Rebecca had cancer and would have died within a few months. Maxim assumes that Rebecca, knowing that she would die, manipulated him into killing her quickly. Mrs. Danvers had said during the inquiry that Rebecca feared nothing except dying a lingering death.

The novel ends with the de Winter’s returning to Manderley to find it ablaze.

The novel was a commercial success, selling nearly three-million copies between 1938 and 1965. She would go on to write many more books and short stories, but Rebecca remains her most beloved. Since its publication in 1938, the book has never gone out print, a clear demonstration of the books enduring legacy. In 2017, it was voted the United Kingdom’s favourite book, beating the likes of Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice and George Orwell’s 1984.

Despite the commercial success of her work, du Maurier was often dismissed as a “romantic novelist”, much to her chagrin. This is an unfair summation of her work, and quite frankly ridiculous. Whilst her works do indeed explore themes of love and marriage, they also explore the paranormal. In Jamaica Inn, du Maurier weaves together a story of pagan ritualism, fated classical tragedy, and atavistic horror. Don’t Look Now tells the story of a grieving father communicating with his recently deceased daughter. The story contains psychic visions, religious premonitions and a murderous dwarf. Rebecca, meanwhile, contains elements that have become synonymous with the horror genre: an ancient, labyrinthine mansion; a sinister woman dressed all in black, and a mysterious death. It is this that elevates du Maurier’s work beyond mere romance. It is this that makes du Maurier one of Britain’s most beloved authors, and why Rebecca has never gone out of print. This is the reason why Alfred Hitchcock, the master of suspense himself (although he had yet to earn this moniker by 1940), chose to adapt not one, but three of her stories.

It is not particularly surprising that Hitchcock was an admirer of du Maurier’s work. Her novels contain many of the same elements that Hitchcock’s movies do. Rebecca has a swashbuckling romance, Gothic psychodrama, a mysterious murder and sexual intrigue.

Rebecca was Hitchcock’s first foray into American cinema and was infamously his only film to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards. The film starred Laurence Olivier, Jane Fontaine and Judith Danvers. It was produced by David O. Selznick. At Selznick’s insistence, the film was a faithful adaptation of the novel, with many of the chapters taken from the pages and put on to the screen. There were ofcourse some alterations, which I shall discuss in one moment. There was however one rather significant plot detail that had to be changed. Rebecca’s demise had to be altered in order to comply with the stringent Hollywood Production Code. In the novels, Maxim intentionally murders Rebecca. In Hitchcock’s adaptation, he merely thinks about killing her, and her death is ultimately an accident. In my opinion, this detracts from the story. In du Maurier’s novel, there is ambiguity surrounding the character of Maxim de Winter. Is he the victim of a narcissistic, emotionally-abusive woman? Or is he a controlling middle-aged man in a toxic relationship with a young, easily manipulated girl? In the Hitchcock movie, it’s the former. Of course, this alteration was unavoidable as the Hollywood Production Code stated that the on-screen murder of a spouse had to be punished. It is a shame nonetheless.

Another change concerns Mrs. Danvers. In the book, and Wheatley’s adaptation, she is older than Rebecca and acts as a maternal figure to her. Screenwriters Robert E. Sherwood and Joan Harrison make Danvers considerably younger so that she is similar in age to Rebecca and added a sexual dynamic to their relationship. The most prominent example of this is the scene in Rebecca’s bedroom, which Danvers has preserved and transformed into a mausoleum of sorts. The housekeeper gives the new Mrs. de Winter a tour around the room, showing her Rebecca’s belongings. Along the way she rubs the sleeve of one of Rebecca’s fur coats against her cheek, explains how she liked her hair brushed, and showing her Rebecca’s underwear draw, where her lingerie lies neatly folded. At one point she stares up at the roof longingly, her eyes glossing over as she reminisces about her beloved Rebecca. Finally, Danvers beckons the new Mrs. de Winter over to Rebecca’s bed and shows her the negligee that belonged to her. Audiences at the time may not have realised the film had anything to do with homosexuality, but contemporary audiences are less ignorant. Mostly.

Both in the book and the Wheatley version, little is revealed about Danvers’ origins. This change, whilst subtle, adds more depth to the character and makes her a more compelling, sympathetic villain. She is still terrifying, however. This is why Mrs. Danvers is held in such high regard among the pantheon of literature and cinematic villains.

Hitchcock famously disliked the movie. Years later, when discussing it with his dear friend and fellow auteur François Truffaut, he disavowed it as "not a Hitchcock picture", due its lack of humour. Despite his own reservations, the film became a commercial and critical success. The New York Times hailed it as "an altogether brilliant film, haunting and suspenseful, handsome and handsomely played". Variety called it "an artistic success", and Film Daily praised the production, direction, acting, writing and photography. The film was nominated for eleven Academy Awards, winning two.

Whereas some films from that era have aged with time, Rebecca is still held in high regard among critics to this day. The film currently holds a 100% approval rating on the review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes. The site's consensus describes it as "a masterpiece of haunting atmosphere, Gothic thrills, and gripping suspense".

With the enduring acclamation of Hitchcock's film, it is bewildering that anyone would want to remake Rebecca. Yet, many have tried. The most recent film-maker to take on the challenge is Ben Wheatley.

Wheatley’s Rebecca stars Lily James as the second Mrs. de Winter and Armie Hammer as her husband. Kristin Scott Thomas rounds at the main cast as the haughty housekeeper Mrs. Danvers. Wheatley reunites with his frequent cinematographer Laurie Rose and together they make a handsome, aesthetically-pleasing movie, and one that, on a superficial level, I quite enjoyed. However, upon reflection, I was rather disappointed. Despite being a faithful adaptation of the novel, in regards to the plot, it fails to capture the mood of the novel. Similarly, whilst Hitchcock’s adaptation was ground breaking with its impressive camerawork and homosexual overtones. Wheatley’s Rebecca is rather mediocre, a bland and unoriginal period film.

When I first learnt that Wheatley intended to make Rebecca, I was pleasantly surprised. I have long been an admirer of his. He is a talented film-maker with an eclectic filmography, but he has a clear affinity with the thriller and horror genre. Kill List is a horrid amalgamation of different movie genres. It begins as a rather slow-aced hitman thriller and family drama, that transforms into a disturbing, visceral horror bonanza. A Field in England, whilst flawed, is a strange, intense and wholly original. Laurie Rose’s cinematography is terrific, with stunning shots of monochrome vistas punctuated by extreme close-ups of plants, insects and tortured human faces. Like Kill List, A Field in England is a mixture of different genres making it difficult to classify. The story is a historical thriller intertwined with a story of occult mysticism and psychedelia.

Wheatley’s other films are as equally eccentric. He often injects clever satire and dark humour into his films. His debut feature, Down Terrace, for example, is an earthly profanely funny crime drama revolving around a criminal family living in Brighton. William Goss of Cinematical said it reminded him of The Sopranos, "had [it] been cooked up by Mike Leigh instead of David Chase", a felicitous comparison. Sightseers is another unique movie, one that blends together the excruciating comedy commonly associated with British sitcoms with the extreme violence of Asian cinema. In 2015, he adapted J.G. Ballard’s cult novel High-Rise, a story about a futuristic residential tower block whose inhabitants succumb to a collective breakdown, seemingly as a result of the building itself. The film is a clever and surreal satire that is exquisitely shot. Free Fire is a raucous shoot-‘em-up comedy that is very reminiscent of Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs. It was a refreshingly bold and exciting movie.

Rebecca is, regrettably, none of these things.

Where is the scathing social commentary from High-Rise? Where is the dry, caustic wit of Sightseers? Where is the transgressive weirdness of A Field in England?

That is not to say the film has no redeeming qualities. It does. It is a very handsome and aesthetically pleasing movie. I give credit to Laurie Rose on making another attractive movie. I also think that the two female leads – Lily James and Kristin Scott Thomas – deliver fine performances.

Despite Lily James appearing in some decent movies (Baby Driver, Darkest Hour, Yesterday) she has yet to impress me with her any of her performances. In Rebecca she delivers a solid performance as the second Mrs. de Winter, successfully capturing the naivety and sweetness that her character is noted to have. I think her performance is hindered by the characters lack of backstory and personality, however, this is the case in the original book and the Hitchcock adaptation. I have more glowing praise for Thomas. When it was announced that she was to take on the role of the haughty housekeeper Mrs. Danvers, I was not surprised. Quite frankly, she was the obvious choice. In interviews, Thomas confessed that this is the role she always wanted to play. Thomas, with her steely stare perfectly encapsulates the character. However, like James, she is let down by the writing. Discussing the movie Thomas said of the character, “she’s not had the life she was expecting to have…we never hear about the husband, but I assume…she'd lost her husband... in the First World War, and then had to become governess to this little girl out of necessity." "She really is frantic with grief, her whole life has been dedicated first of all to this girl, Rebecca, and then to the memory of the girl, and then it's all taken away from her and she's got nothing left…” I agree, it could have displayed Danvers in a more sympathetic light if this had been explored . It could have quite touching, but it wasn’t.” I agree, it could have been quite touching, if it was conveyed slightly more in the film. It isn’t though. This is a real shame.

The only actor that I think is miscast is Armie Hammer. I am generally a fan of Hammer's. In The Social Network he delivers a strong performance as the preppy Winklevoss brothers. In Free Fire, he is smarmy, arrogant and incredibly charismatic. His finest performance is in Luca Guadagnini's coming-of-age masterpiece Call Me by Your Name. His performance is complex and moving. His performance in Rebecca is neither of these things. I shall talk more about his performance later, however.

I am now going to make an obvious analogy, and one that I have seen many other commentators make and have done so with more eloquence than myself. Hitchcock’s Rebecca is comparable to the first Mrs. de Winter. In du Maurier’s novel, Rebecca is beloved and celebrated by all who knew her. She haunts every single page of the book. Similarly, Hitchcock’s Rebecca is still held in high regard among critics and cinephiles today. Because of this, all subsequent adaptations of Rebecca have been compared to it. The remainder of this short essay will seek to compare Wheatley’s adaption with Hitchcock’s and explain why Hitchcock’s version is not only more faithful to du Maurier’s novel, but is also the superior adaptation.

Whilst both films are fairly faithful adaptations of the novel, they do make some alterations. This is clear from the start. In Hitchcock’s movie, the future Mrs. de Winter happens upon Laurence Olivier’s Maxim as he stands at the edge of a cliff, staring down at the waves below and seemingly contemplating suicide. When she calls out to him, Maxim claims that he is fine, and they part ways. The two meet again later that evening at the hotel where they both happen to be staying. From this point on their dalliance proceeds the same way it does in the novel with Mrs. Van Hopper falling ill and the two sneaking off on romantic trips. Despite their blossoming romance, the audience do not forget how the couple first met. Despite his charming exterior, the audience understand that there is more to Maxim than meets the eye, and that things are not as romantic as they may currently seem. I think this was a very clever change to the source material.

In Wheatley’s version, the meeting between the future Mr. and Mrs. de Winter is more faithful to the novel, and far less ominous. It is more of a traditional romantic-comedy ‘meet-cute’, something you might expect to see in a Richard Curtis movie. Lily James’ young companion, at the behest of Mrs. Van Hopper is trying to bribe the concierge into seating her employer next to Mr. de Winter, completely oblivious to the fact that he is stood behind her. After she clumsily drops the bribery money, the mysterious gentlemen helps her pick it up. As he does so he mentions that this “Maxim de Winter fellow is quite the bore.” It is only when the manager addresses him later that she realised who he really is. Whilst amusing, their initial meeting does not foreshadow the tragedy that will come later.

This brings me on to one of my significant criticisms of Wheatley’s Rebecca. Armie Hammer, whilst tall and handsome, is horribly miscast. He is far too young for the role. Both in the novel and Hitchcock’s movie, Maxim is considerably older than his new wife. This is referenced frequently, with Maxim raising the concern that he is old enough to be her father numerous times. This contributes to the new Mrs. de Winter’s growing insecurity. She begins to doubt his love for her, and begins to wonder whether he merely chose her because he was lonely at Manderley, and wanted someone young and pretty to pass the time by with. It also adds an air of mystery to the character. The fact that he is older and he has lived a life before the new Mrs. de Winter makes him all the more enigmatic.

It is very likely that du Maurier based the character of Maxim de Winter on her late actor-manager father, Sir Gerald du Maurier. She adored her father but admit he could be quite domineering. A few years before she wrote Rebecca, her father passed away. Du Maurier refused to attend the funeral but did later write an astonishingly candid biography, Gerald: A Portrait. She detailed her father’s vanity and alcoholism, and explained that, despite his outward charm, he would have the most awful of mood swings. It is quite clear that some of Maxim de Winter’s characteristics and personality traits were inspired by her father. Sometimes he is the epitome of charm, whilst at other times he seems emotionally sequestered. Sometimes he is cantankerous, whilst at other times he is caring. Laurence Olivier perfectly encapsulates this duality.

Olivier possessed undeniable charm and it oozes from him from every scene. This makes it all the more upsetting when he does lose his temper with his new wife. He also perfectly captures the nuances of the character. Armie Hammer simply does not compare. Hammer seems to be devoid of emotion throughout the entire movie. Perhaps, this is because he is focusing on his accent rather than his overall performance. Because of this, Hammer also fails to convey the conflict inside Maxim. Maxim de Winter is a tortured soul, guilt-ridden because of the murder of his wife, and the hatred he still has for her even though she's no longer with him. Olivier perfectly captures the inner turmoil within the character. Hammer, in contrast, just seems a bit of a grumpy bore.

Perhaps, my main criticism of the movie, however, is its representation of Rebecca. Now of course, she does not physically appear in the novel or Hitchcock’s film, but we are constantly reminded of her throughout. Du Maurier is able to do this through the use of first-person narration. She quite literally puts the reader into the mind of the new Mrs. de Winter. We see the world as she does. We feel how she does. The reader understands the effect Rebecca has on the protagonist. Hitchcock does the same through the use of the moving camera. His pervading eye lingers on the shots “R de W” monogrammed handkerchiefs, books and other memorabilia, constantly reminding us of the “magnificent and beautiful” Rebecca. Wheatley reminds the audience in a less subtle way. During a party the new Mrs. de Winter pursues a random lady in a dress whilst the other revellers chant “Rebecca”. Whilst it was a beautiful little sequence, that once again demonstrates Laurie Rose’s prowess behind the camera, it was still rather ham-fisted.

My main gripe with Wheatley’s adaptation however, is that it fails to capture the essence of the novel. As I said earlier during my introduction, Daphne du Maurier is not a romance novelist. Whilst her novels do have romances and marriages, Rebecca certainly does, they also focus on the paranormal. In this regard, du Maurier’s novels have far more in common with “sensation novels” which reached peak popularity during the 1860’s and 70’s. These novels would often combine romance and Gothicism, and deal with shocking subject matters like adultery, insanity, seduction and murder. Rebecca has all of these elements.

It is this that that attracted Hitchcock in the first place, and this is all reflected in the cinematography. His movie, whilst beautiful, is full of tension. With the help of his cinematographer, George Barnes, and his art director, Lyle. R. Wheeler, Hitchcock is able to create an atmosphere of dread through the use of deep focus photography. Joan Fontaine’s Mrs. de Winter appears Lilliputian in the cavernous environs of Manderley. Similarly, Mrs. Danvers grim and skeletal frame is made interminably more terrifying when backlit and shot from below, transforming her from a dull housekeeper into a harbinger of doom. Wheatley’s Rebecca, in contrast, is a rather conventional period piece.

Yet, Wheatley’s Rebecca is more of a romance drama, than a Gothic thriller. This was intentional on Wheatley’s part and, in all fairness, it was not meant as a remake of Hitchcock’s Rebecca, so perhaps comparing the two is a little unfair. In an interview with Sight & Sound, he states that it is “clearly an adaptation of the book”. It wasn’t a remake of the film…Why would you want to remake a Hitchcock film, and one that won so many Oscars?” He expands on this in an interview with Empire. He explains how he wanted “to make something that had more love in it.” “Rebecca has dark elements, and it has a psychological, haunting story within it, but it’s also about these two people in love. That was the main thing.”

This is where I think Wheatley is mistaken. Rebecca is more than just a romance. He downplays the paranormal aspects, and in doing so ignores what makes Rebecca such an impactful book, and du Maurier a legendary author. He has just made another “romance” film.

I have been to Manderley numerous times, having read Daphne du Maurier’s novel twice and watched Hitchcock’s version numerous times. I don’t think I want to go again any time soon.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.