'Get Out' and the Black Renaissance of the 2010s

How the 2010s Saw an Increase in the Diversity of Topics in Black Media

Many would say that we are currently in the middle of a new black renaissance in terms of film and television. Black artists like Jordan Peele, Lena Waithe, Ryan Coogler, Issa Rae and Ava Duvernay have built platforms that have put them on the same level of consideration as white artists through films such as Get Out, Black Panther and Girls Trip, and shows such as Insecure and The Chi. They have proven that black creativity can generate just as strong numbers as white creativity, if not stronger (as seen with Black Panther). However, many might also argue that this isn’t the first black renaissance that we’ve experienced in American media. The blaxploitation era in the 70s is often considered to be the birth of African American cinema. The 1990s are also frequently mentioned as a black renaissance for television in particular, with so many iconic sitcoms produced by notable black figures in entertainment. But the black renaissance of the 2010s might be the most important black renaissance in American history.

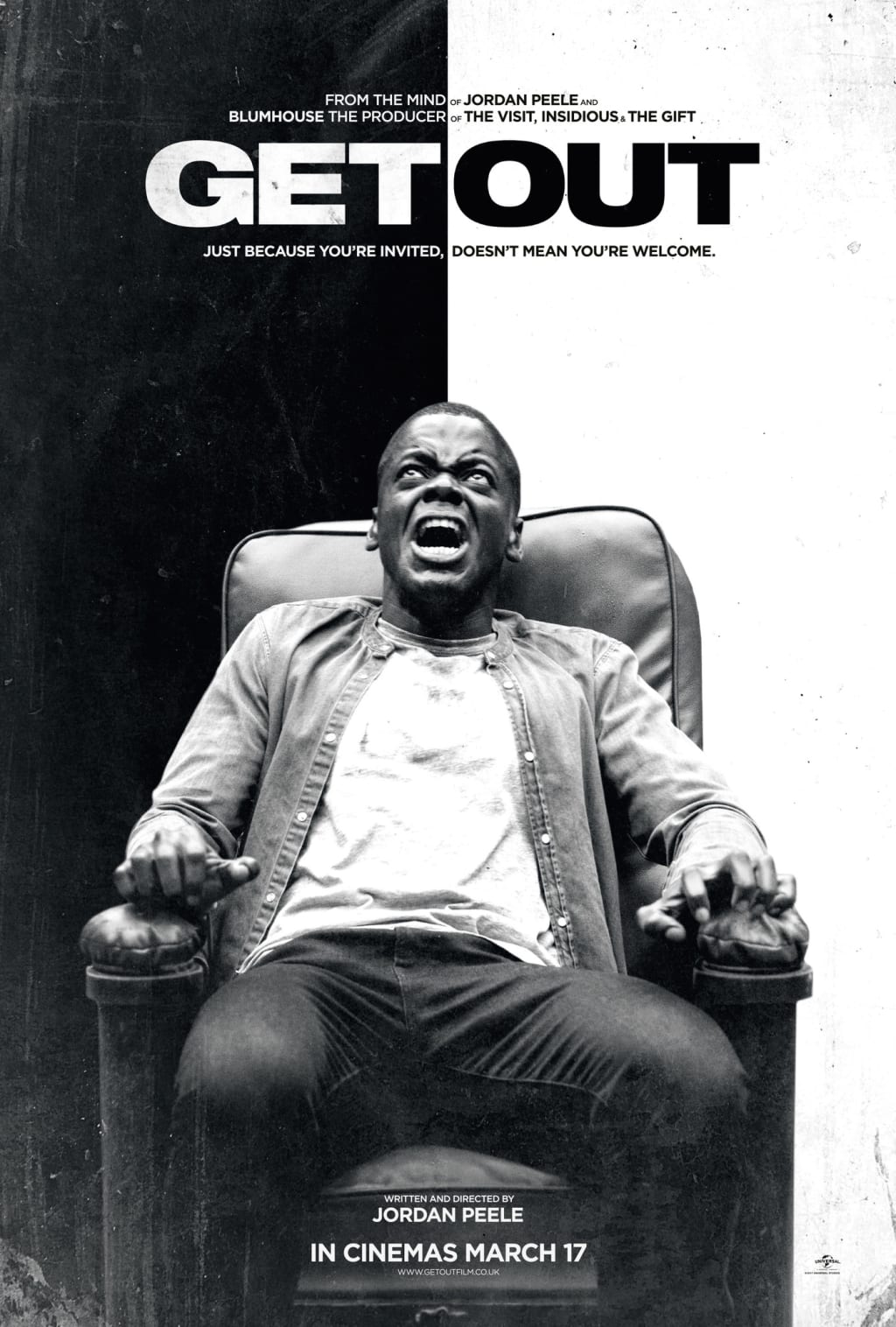

The one thing that the 1970s and the 1990s had in common was that black media at that time was expected to fit into a certain mold. Blaxploitation films of the 1970s were usually centered around violence in impoverished urban areas. The sitcom boom of the 1990s produced shows that primarily centered around a main character living with a group of friends or family members and incorporated themes of love, sex, relationships and family, with the occasional episode about larger social issues such as police brutality or racism. Even the black films of the 2000s were forced into a mold. They were usually either films depicting (often highly dramatized) situations in the “hood” or romantic melodramas about dysfunctional relationships, popularized by Tyler Perry. But in our current black renaissance, the rules are nearly non-existent. We are seeing black filmmakers explore things that were never dared explored before, such as being LGBT in the black community, Afro-futurism, Afro-superheroism, or simply films about characters in situations that aren’t defined by their blackness. Black creatives finally have the freedom to be experimental. And it doesn’t get more experimental than Jordan Peele’s 2017 horror masterpiece, Get Out.

To call Jordan Peele’s Get Out a “hit” would be a vast understatement. The film was produced on a modest budget of only 4.5 million and went on to gross over 200 million in the global box office. The first public trailer for the film was attached to the 2016 BET awards, and it was met with overwhelming skepticism. In How Hollywood Stole My Identity: African American Representation, in the films Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and Get Out (2018), it is shown that many critics thought that the concept was anti-equality and promoted the idea that white people are evil. Initially, the film had nothing going for itself. It didn’t have an A-list cast, the director was a comedian known for his often lackluster humor, and it was released during the first quarter of the year, which is usually when the worst films are released. Peele himself knew that this film was risky. With its’ heavy subject matter that hasn’t been extensively explored in cinema, he thought it would go over the audience’s heads. During his acceptance speech at the Oscars, he stated,

“I stopped writing this movie about twenty times because I thought it was impossible.”

Even I myself am guilty of doubting the film upon its announcement. I remember commenting on how cheap the film looked and and thinking “a horror film about race? That’s just stupid.” It wasn’t until the films perfect Rotten Tomatoes score was released that the public began taking the film seriously. I remember watching it in a packed theatre with my friends on opening night,

One of the most common things said about this film is that it needs to be watched more than once in order for the viewer to fully receive it. I personally saw the film three times in the theatre and an additional three times after its home release. Every time I watch it, I pick up on a new subtle detail that I never noticed before. Peele was very meticulous in weaving a deeper meaning into every shot, line of dialogue and even character in the film.

The overall theme of the film is the appropriation of black culture across the globe and the commodification of black bodies. It is a statement on how the black lifestyle is romanticized and sought after, until it’s time to face the reality of the hardships that African Americans face on a daily basis. The details are overtly displayed in the film, particularly during the garden party scene. The protagonist, Chris, is bombarded with questions and comments about his race by the “customers” hoping to purchase his body for the brain transplant. One of them asks him about his golf swing and explains that he used to be very good at the sport, while also mentioning Tiger Woods. A woman makes comments on his physique and feels his muscles, implying that she wants his body for her sick husband while also portraying the sexualization of the black male body. Even though these make up the overarching theme of the film as a whole, the film uses a variety of techniques to represent multiple aspects of the perils of African American life in America.

One of the best ways to talk about how representation is used in the film is to analyze each member of the Armitage family individually, and analyze their roles in the operation. The process begins with Rose, the angler for the family. Rose is responsible for luring black men (and occasionally women) to the household for the operation. She represents the fears of interracial dating in the black community stemming from an era when a black man could be killed for having relations with a white woman. The Emmett Till case is one of the most famous examples of this. The character of Rod, Chris’s best friend, hits on this point multiple times throughout the film, waning Chris that he should be careful when dealing with her family. Roses character arc also brings to mind images of the black brute, the large, violent, dark-skinned black man (often depicted as ape-like) who forcefully lusts after innocent white women. Raquel Gates goes into detail on this in The Last Shall Be First: Aesthetics and Politics in Black Film and Media (2017). She tries to play this card during the climax of the film when the cops arrive as Chris is choking her in the street.

Rose’s brother, Jeremy, is the muscle of the operation. He is there to handle the subjects who might try to rebel against the family. Jeremy represents the long history of the commodification of the black body, from slavery all the way to professional sports. This is presented almost as soon as he is introduced, during the family dinner. He bombards Chris with questions about his athletic history, which is his way of testing out his strengths and weakness for when he inevitably has to fight with him. He mentions his “frame” and “genetic makeup," and suggests that if Chris were to train and apply himself, he’d be a force to be reckoned with. This speaks to the idea that the white man knows what’s best for the black body, more so than the black mind. This is the idea behind their entire operation.

The father, Dean, is the surgeon in the operation. He is responsible for performing the surgery that places the white patients brain into their new black body. Dean represents the obliviousness that many white people have toward their own racism. He also represents the postracial myth and the desire to erase the hardships that African Americans have gone through at the hands of whites, which was explored in Can I Live? Contemporary Black Satire and the State of Postmodern Double Consciousness (2016). Throughout the film, Dean comes across as this “down for the cause” guy who loves black people but only on the surface. He says shallow things to get on Chris’s good side like “I would’ve voted for Obama for a third term if I could.”

The mother, missy, is probably the most symbolic member of the family. Her job is to hypnotize the black victims’ minds in order for the operation to go smoothly. She does this in two ways. First, she hypnotizes them into falling unconscious on command, making them easy to control. This represents how the black community has been brainwashed over generations to make them easier to control by white patriarchy. Next, she places the victims’ consciousness in a submissive state known as “the sunken place.” In it, the victim floats in an endless void as they watch someone else control their body from their point of view. This is a metaphor for the prison industrial complex. The black person has to watch the world go on from inside the prison that was created to profit off of them.

From a psychoanalytic approach, the underlying theme of the film is black fear. Peele dove into his own experiences as well as the collective experiences of the black community as a whole to portray various fears commonly experienced by the African Americans. The fear of the police is exhibited twice in the film. We first see it as Chris and Rose are on their way to the Armitage house. They are stopped by a cop after hitting a deer, and the cop asks for Chris’s license even though Rose was driving. The black audience is on edge, as we know how these types of interactions can turn out. This fear is exhibited again at the end of the film when the police car pulls up as Chris is choking Rose in the street. I remember this being the most gut-wrenching part of the film for me, despite all of the other horrible things that happened in the film. The reaction from the audience confirmed that Peele was spot-on in expressing this fear.

In Paul Doro’s article Thirty-Five Years of Middle-Class Fears: How Two Poltergeists Address Race, Class, and Gender (2018), he talks about “the suburban dream,” the idea of the white suburb being the ideal American sanctuary, and how this idea is commonly used in horror films such as Poltergeist. Showing white suburbs as an isolated epicenter for dysfunction and horror plays a major role in building the world of Get Out. This is also connected to the fear of “wasp families,” old-fashioned white families that seem almost too perfect. Zadie Smith goes into depth about this in the article Getting In and Out: Who Owns Black Pain? (2017).

I mentioned earlier that the fear of interracial dating is a primary theme in the film. This fear isn’t limited to the individual. The fear of meeting the family of a different-race partner plays a critical role in the film. With Peele himself being biracial, and in an interracial marriage, he was able to perfectly convey this theme through the Armitage’s microaggressions and Chris’s very first like of dialogue; “do they know I’m black?”

There has never been a film like Get Out. Every aspect of the film, from its’ production to its’ subject matter is entirely unique, which is why it is such an important film. Not only does it teach valuable lessons on social issues and our contemporary society, but it teaches an even bigger lesson to aspiring black content creators, such as myself. It teaches that there isn’t only one way to make a film as a black creator. No matter what you want to make, even it isn’t what the other black filmmakers are making, there is a market for it. This is the defining theme of our current black renaissance.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.