False Positive and the chilling dramas exploring infertility

New psychological horror False Positive is among the many films and shows that channel our primal fears, and challenge the patriarchy. What can they tell us

If birth is the most elemental aspect of life, what happens when fertility and motherhood are threatened? In the new psychological horror film False Positive, Lucy, a woman who has struggled to become pregnant, suspects she is being gaslit by her controlling husband and their charming fertility doctor. Ilana Glazer, its star and co-writer, described it in a perfectly distilled phrase. "It's about the patriarchy as expressed through medicine," she said.

Glazer's line is more than a pithy talking point, and False Positive more than a gloss on the enduring thriller Rosemary's Baby (although the echoes are unmistakable). Infertility is the subject driving some of today's most dynamic films and television series. Filmmakers use the zeitgeisty issue as a window on urgent social blights ranging from climate change to sexism and class privilege. The trope is equally effective in dystopian nightmares and works of exacting realism because, whatever the style, infertility dramas allow us to see primal fears play out on screen.

Novelists seem to have connected infertility and social upheavals first, with filmmakers soon adapting those worst-case scenarios. In Children of Men, Alfonso Cuarón's 2006 instant classic based on PD James's book, infertility is inseparable from the Orwellian dystopia in which all women in the world have mysteriously become barren. Infertility drives the plot, but the message is about who has political power. When one woman finally becomes pregnant, the state and warring rebel factions threaten to take her child after it is born because she is poor, black and a refugee. The film's landscape of refugee camps in an authoritarian state are even eerier and closer-to-home today than ever.

Films use infertility as a way to explore fears more often than hopes because the worst-case scenario is usually a better story

Margaret Atwood made a more pointed connection between infertility and dystopia in her novel The Handmaid's Tale, the source of the television series now in its fourth season. There have been so many twists in the harrowing life of the handmaid at its centre, June Osborne (Elisabeth Moss), that it's easy to forget the story's beginnings: a drop in fertility worldwide led to the creation of the state of Gilead, where fertile women are used as sexual slaves, their children given to the infertile wives of the state's so-called Commanders. This season, Commander Waterford, who had enslaved June, continues to defend Gilead, saying, "Where else on Earth is the birth rate rising?"

Infertility has become such a potent trope partly because these exaggerated fictions are based in reality. Atwood's novel makes a direct connection between toxic chemicals and a drop in fertility. Scientific studies mirror the fiction, showing, for example, that sperm counts have dropped, with one widely accepted theory pointing to environmental causes. According to the World Health Organization, it is difficult to assess fertility rates accurately, and now Covid has skewed results. But in the US the birth rate was in decline even before the pandemic. And in vitro fertilisation (IVF) has become more commonplace over the past several decades. Yet those treatments remain extremely expensive, exposing economic and class fault lines, ready-made for dramatic plots.

Before in vitro was a reality, fears about pregnancy and birth in films more often took the form of a devil-baby. The adopted demonic child Damian in The Omen (1976) now looks like an influencer, inspiring sequels and copycat films. The Demon Seed (1977), in which a computer with artificial intelligence impregnates Julie Christie's character, may have been ahead of its time in using pregnancy to express fears about new technologies.

Truly chilling

The classic example of a pregnancy horror-film, of course, is the still-chilling Rosemary's Baby (1968), to which False Positive owes a huge and knowing debt. Both movies feature a lying husband, an evil doctor, the gaslighting of a trusting wife, and supposedly supportive but possibly duplicitous friends. But the new film is also notable for the way it veers away from the strict horror genre, focusing on more realistic threats.

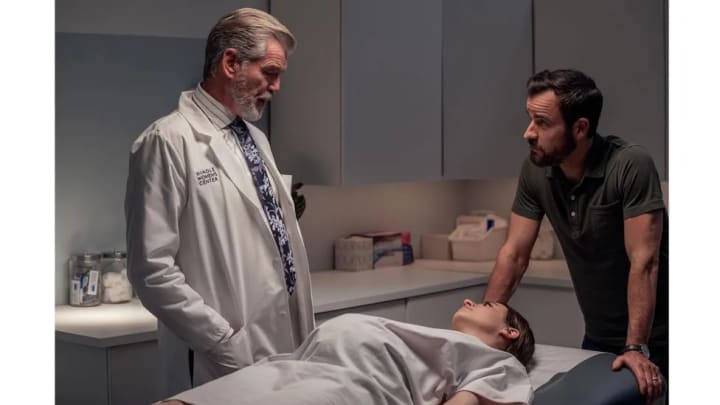

Director John Lee, who wrote False Positive with Glazer (Broad City), deftly blends Lucy's nightmarish fantasies with credible scenes from her privileged life with her husband, Adrian (Justin Theroux, who finds the right uneasy balance between attractive and sinister). The first scene shows a stunned Lucy in a blood-soaked shirt slowly walking down a dark, empty street. The police cars and ominous music that follow suggest she has been involved in something horrific. But the story then flashes back to ordinary life, where we see her disappointment at the latest negative pregnancy test. Adrian convinces Lucy to see his old mentor, the famous Dr Hindle. Pierce Brosnan plays the doctor, smoothly condescending to Lucy.

Beneath the horrors, dystopias and melodramas about infertility are real-life themes

The film's true power comes from the questions about science, ethics and sexism that Lucy faces. When she becomes pregnant with three embryos, Hindle recommends reducing by one or two for her own and the babies' safety. When she and Adrian disagree about whether to eliminate the girl or two boys, who gets to make that decision? Unlike Rosemary's Baby, here the devil is in the social structure, and in the way men try to take charge of Lucy's body and her future.

The themes of economic privilege and infertility also shape the captivating BBC melodrama The Nest, a 2020 series in which a wealthy couple unable to have a child hires a surrogate mother. Playing the couple, Martin Compston and Sophie Rundle make their characters complicated and ultimately sympathetic, as everything that could go wrong for them does. Because paying a surrogate is illegal in the UK, the rich husband is blackmailed. The young working-class woman who has ingratiated herself as their surrogate has lied about her dark past. And the wrong egg is mistakenly implanted. Like False Positive, The Nest is a thriller that plays to entirely plausible, if overloaded, scientific and social fears.

Realistic dramas have also been depicting in vitro as a common option. In the film Private Life (2018), Kathryn Hahn and Paul Giamatti are a couple who choose IVF, along with all the hormone shots, mood swings, marital tensions and procedures to implant an egg that come with it.

This season's Master of None focuses on the character of Denise (Lena Waithe) and her wife, Alicia (Naomi Ackie), and devotes an entire eye-opening instalment to IVF. After the couple divorces, Alicia decides to have a child alone. In physical and emotional detail, the intimate episode takes her through the tests, treatments, hopes, disappointments and tough choices she has to make. Can she even afford IVF?

The episode, which is not about infertility, helps normalise the way scientific advances have helped women have children. But it also reveals harsh social inequalities. A fertility doctor, a sympathetic woman, regretfully tells Alicia that her insurance will not cover the IVF treatment because she hasn't tried to conceive with a partner. "They don't have a policy for queer people?" Alicia asks. The doctor explains that insurance companies need a diagnosis code to confer benefits and that, "The majority of American insurance companies do not have a code for 'gay and desires pregnancy' or 'single and desires pregnancy'".

It's not surprising that films more often use infertility as a way to explore terrors rather than hopes, though. The worst-case scenario is usually a better story. But there is more than enhanced drama beneath these dystopias and melodramas. From Children of Men through False Positive, films grapple with the question of who controls women's bodies. The question of money, and the possibility of science, run amok hover over every scene of a woman or a couple considering IVF. As these themes are splashed out on screen, they touch sensitive, real-life issues that are increasingly central to our current political and social landscapes. Today it doesn't take a demon-baby to explore our deepest fears.

About the Creator

Mao Jiao Li

When you think, act like a wise man; but when you speak, act like a common man.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.