At this year’s Venice Film Festival, there was no bigger talking point than The Painted Bird. The new film by Czech director Václav Marhoul is a black-and-white adaptation of the 1965 novel by Polish-American novelist Jerzy Kosiński, which describes World War Two from the perspective of a young Jewish boy on a journey through the horrors of Nazi-occupied Europe. Its press and industry screening inspired walkouts on three separate occasions, ensuring the film a certain period of notoriety. This was followed up by further walkouts a week later during its North American premiere at the Toronto Film Festival.

Some who could brave Udo Kier as a sadistic miller gouging out a man’s eyes, couldn't then stomach the moment that a promiscuous woman was murderously set upon by a brawling gang of her fellow villagers. And then there were those for whom the brutal Cossack attack was the final straw.

Whatever the exit moment, was this in fact an occasion for the film world to celebrate? It did, after all, suggest that cinema still has the power to shock – something many had begun to doubt.

Xan Brooks’ review of The Painted Bird for The Guardian captured the sense of surprise that a film could still make people leave a screening at a film festival. “One day they'll make a film about the first public screening of The Painted Bird…,” he began.

However Marhoul dismisses claims that he set out to shock audiences: “I understand that some people left the cinema," he tells BBC Culture. "As a director, I made this movie without any compromise, but I don't think there is explicit violence.”

He emphasises that actually the much-discussed violence isn’t explicit: it’s all in the power of suggestion. “When the miller is putting the spoon on the eye, do you see it? No,” he says. “The explicit scenes are only in your brain, not in my movie. This film in terms of the violence and brutality is not only very decent, but it is also truthful.”

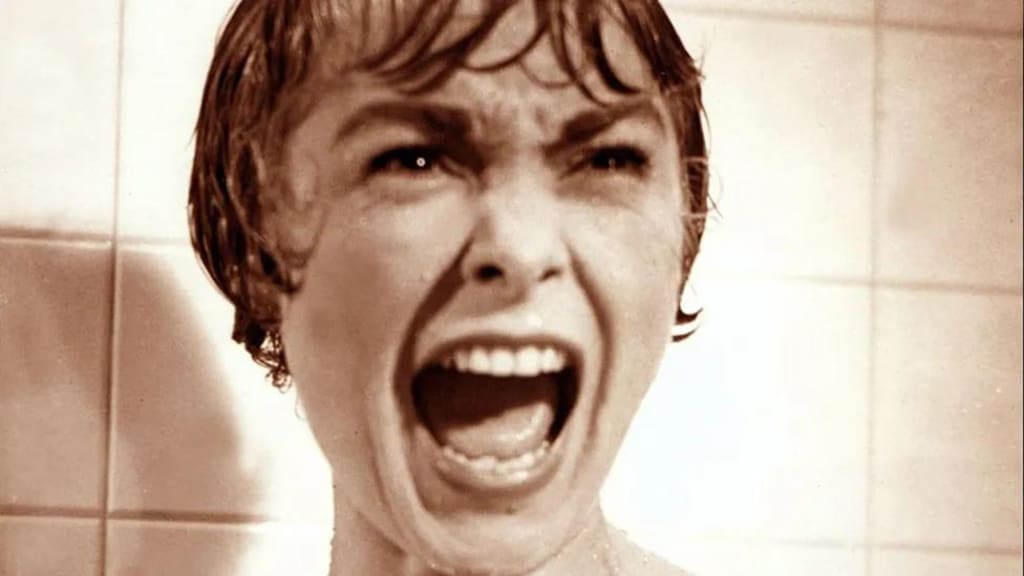

The power of suggestion

The director argues that the walkouts are testament to the film’s real emotional power – it’s because audiences recognise reality and honesty in his film that they react so violently. He contrasts his approach to the pop-violence of someone like Quentin Tarantino, whose films he argues are much more graphic. “If you are watching a Tarantino movie, the guts are spraying around, and you are okay because that is a fairy tale,” he says. “Then you watch The Painted Bird, that depicts incidents you believe might happen, and you are going to be touched.”

Indeed, Marhoul asserts that it is only through the power of suggestion that you can really shock audiences these days. It’s not what the audience sees that's important, but what they imagine.

A few weeks earlier, meanwhile, Locarno Film Festival hosted the world premiere of another film that shocked audiences for different reasons: Dutch filmmaker Halina Reijn's debut feature Instinct, which stars Game of Thrones actress Carice van Houten as a psychologist who is infatuated with a sex offender she is treating at a prison.

People advised me not to show the penis. Now I'm thinking what the hell – where are my penises? Halina Reijn

A woman in power in love with a rapist is a taboo subject. The film, which will play at the upcoming London Film Festival, suggests that there is something inherent in humans that pushes them to seek out danger. The violence in the film is both physical and mental.

Like Marhoul, Reijn didn’t set out to shock people, but says she does “like plays or movies or paintings that provoke something. I'm sometimes shocked a little bit by Instinct myself,” she continues. “I was intrigued by the story because of the elements of sexuality and power.”

As a female director, Reijn also wanted to reclaim the power of provocation, she says; she feels that cinematic history is full of male directors defining transgression, and now she wants to change the script and push audiences buttons in a different way. As part of that subversiveness, she decided there would be no female nudity in the film, only male nudity. “People advised me not to show the penis. Now I'm watching Euphoria on HBO and Midsommar thinking what the hell, where are my penises?” she laughs. The shocking element of her work comes not from being explicit – but from challenging norms.

What’s clear is that both Marhoul and Reijn view shocking audiences, whether intentionally so or not, as an achievement of sorts – a sign that they are challenging audiences and asking the right questions.

A state of flux

The trouble in trying to shock is that what is shocking and taboo is constantly in flux. To take the example of male nudity, it has traditionally seemed more shocking to see male than female genitalia on screen because of its comparative infrequency. But as it has featured more and more in TV and film recently, so it already no longer seems taboo.

Cinema reflects changes in our public consciousness, and consequently the nature of transgression changes. But it is not the case that to shock, directors simply have to push boundaries and become more and more explicit. Of course, the limits can change so that things that seemed fine in the past can now become shocking.

What shocks audiences today is not often to do with what appears on screen – so much as the thinking or ideology behind it.

To take a recent example from the small screen, in July Netflix removed a three-minute suicide scene from the end of season one of 13 Reasons Why following a sustained public outcry. It featured the lead character Hannah (Katherine Langford) taking her own life in a bathtub. Strangely, the decision to alter the scene came two years after the episode first aired, and became available on the service.

However it wasn't the scene‘s graphicness in itself that was the problem – after all, there are many scenes of gore to be found on Netflix. It was to do with the specific concerns that have grown up around depicting suicide – and the copycat suicides any detailed depiction might inspire.

When the scene was deleted, showrunner Brian Yorkey released a statement saying: “we have heard concerns about the scene from Dr Christine Moutier at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and others, and have agreed with Netflix to re-edit it. No one scene is more important than the life of the show and its message that we must take better care of each other. We believe this edit will help the show do the most good for the most people while mitigating any risk for especially vulnerable young viewers.”

In fact, though, what shocks audiences today is not often to do with what appears on screen – so much as the thinking or ideology behind it. Andrew Simpson, Director of Film Programming at Tyneside Cinema in Newcastle, says: “We rarely get complaints about content for the films that we show. When we do get complaints, it's more that the customer feels offended by an idea in the film, a representation of a character, or something that offends their identity.”

It marks a big sea-change in what can be understood as ‘shock cinema’.

People walking out of films has been part of the cinematic experience since the first ever public film screening, by the Lumiere Brothers, of a train arriving at La Ciotat station in 1896, which was so realistic that it apparently caused the audience to stampede out of the cinema.

Urban legend or not, the story demonstrates cinema’s fundamental power as a visceral, real experience which, at its best, can delude spectators into thinking that the images they watch have an impact beyond the screen.

The history of ‘shock cinema’

Consequently, provoking a reaction has come to be one of the metrics by which we judge cinema's quality. From the very beginning, filmmakers started to capture images that broke societal taboos. Cinema created moral outrage.

The reaction to this outrage was regulation over what images were acceptable for consumption by the general public. It was the start of a censorship system that continues today, albeit in a different guise.

In the US, the 1930 Motion Picture Production Code or so-called Hays Code – set out guidelines for what was acceptable content for motion pictures produced on home turf.

For two decades, the guidelines were rigorously enforced. But after World War Two, directors such as Otto Preminger began to test the boundaries. Preminger caused problems by using the words ‘virgin’ and ‘pregnant' in his 1953 comedy The Moon is Blue and depicting heroin addiction in The Man with the Golden Arm (1955).

In the face of these challenges to its authority, enforcement of the Hays Code began to wane. Filmmakers operating outside the mainstream, such as Kenneth Anger, Jonas Mekas and Jack Smith, made counter-culture films branded as ‘underground’ films, which seemed designed to upset.

In the 1970s, European auteurs were determined to destroy any boundaries of taste

Meanwhile Europe was testing the limits of what was acceptable even further. The European obscenity laws were liberalised in the late 60s and early 70s, but auteurs were determined to destroy any implicit boundaries of taste, for decidedly varying motives. Walerian Borowczyk directed Emmanuelle '77 seemingly for prurience, while Bernardo Bertolucci's Last Tango in Paris (1972) and Oshima's In the Realm of the Senses (1976) seemed to be engaged in a more avowedly artistic mission to bust sexual taboos.

In the UK in 1972, press and lawyers linked Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange to real-life crimes taking place. The film had been passed uncut by censors. Nonetheless, Kubrick instructed Warner Bros to pull the film from British cinemas. At the same moment, he released a statement denying the power of art to make people act beyond their nature.

During the 70s, revered filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard (Numéro Deux), Pier Paolo Pasolini (Salo) and Miklós Jancsó (Private Vices and Public Virtues) were similarly condemned for their content, and had works banned. What their films shared was a concern with obsession and the intersection of power and sexual relations.

Back in the US, in 1968, the Hays Code was replaced by a new rating system in the wake of Arthur Penn's challenging, nihilistically violent Bonnie and Clyde. A year later, Denis Hopper's sex drugs and rock ‘n’ roll biker movie Easy Rider ushered in the New Hollywood era. Busting taboos started to equal big box-office and Oscars.

Another underground film movement, The Cinema of Transgression, followed. It centred on humorous movies very consciously designed for shock value; its defining moment, and still one of the most shocking moments of cinema, came in John Waters' Pink Flamingos (1972), when the cross-dressing actor, Harris Glenn Miller, better known as Divine, ate dog faeces on screen.

By 1980 however, just as Jaws and Star Wars gave birth to a newly-energised mainstream with the blockbuster movie, so shock cinema seemed to come to an abrupt stop.

It wasn’t until the mid-90s when cinema really found a desire to shock again. Filmmakers suddenly seemed to be in competition to outmatch each other’s perversity: David Cronenberg's Crash (1996), an adaptation of the JG Ballard novel, saw people gaining erotic pleasure from car accidents. Danish auteur Lars von Trier made a series of troubling films, reaching its apex in The Idiots (1998), which features an orgy made-up of people pretending to be mentally ill. Michael Haneke's The Piano Teacher (2001) cut sex and self-mutilation together.

The end of outrage?

In 2002, Gaspar Noé took Irreversible, a thriller that featured a nine-minute rape scene, to the Cannes Film Festival. There were mass walkouts and outrage. A year later, Vincent Gallo's The Brown Bunny upset festival-goers because of an unsimulated fellatio scene involving actress Chloë Sevigny and the director and star Gallo.

Arguably, no single film since then has inspired such levels of collective shock. Irreversible is now considered a cinematic classic. The director even came to this year’s Venice Film Festival with a new version of the film, called The Straight Cut, where the previously-reversed action unfurls in chronological order, so that a story that originally began with its anti-hero taking horrific revenge for the sexual assault of his girlfriend (Monica Bellucci) now ends with that scene.

Narrative cinema is getting so mild nowadays. The most shocking thing today is the news. The world is turning psychotic – Gaspar Noé

In many ways, it's even more brutal than the original version. Now, it starts in a place of happiness and ends in chaos and despair. The rape scene is as brutal as ever, all the more so as we now get to know Bellucci's character before she gets stopped in a tunnel. However there were no walkouts, and the film played with little controversy.

Speaking in Venice, the Argentinean born Noé told BBC Culture that he thinks it is nearly impossible to shock audiences today, such is the proliferation of disturbing images available on the Internet. “Everybody knows that the actors don't get hurt on the set and there is a crew behind the camera. Narrative cinema is getting so mild nowadays. The most shocking thing today is the news. The world is turning psychotic.”

The kind of humour I did is now American humour. It's normal – John Waters

Another shining example of the transitory nature of transgression came at this year’s Locarno Film Festival, when John Waters was awarded the festival's top honour, the Pardo d'onore Manor lifetime achievement award. It was the ultimate establishment validation of an artist who was once a mainstream pariah.

Waters is a man whose nicknames include the monikers ‘People's Pervert’ and ‘The Pope of Trash’. “All ‘underground films’ caused trouble and the directors would get arrested,” he recalls.

Now a lot of those films feel quaint and kitsch. It's hard to imagine Waters making a film today that could cause the same level of offence, although he protests that his early works still possess some shock value for newcomers. “I don't know if they're that quaint. Pink Flamingos still works. I think if you're 20 and see it for the first time, it didn't mellow that much.” He does concede that his sensibility is more mainstream these days, however. “The kind of humour I did is now American humour. It’s normal.”

If Easy Riders, Irreversible and Pink Flamingos no longer generate outrage however, then there is one of the aforementioned ‘shock films’ of old that is even more shocking than when it premiered – and that fact speaks volumes about our shifting values. That is The Brown Bunny.

It wasn't simply the nature of the graphic scene itself that offended at the time. Viewers were also concerned with Sevigny having to submit so physically to the will of the director, as well as the fact that the unsimulated nature of the sex act arguably crossed the line that distinguishes cinema from pornography.

At heart, the transgression of The Brown Bunny is not the sexual content in itself. It’s the power relationship involved. The potential for real-life, but invisible exploitation behind the scenes has, rightfully, become much more shocking to us than anything that we can see on screen.

Where other films’ notoriety feels of its time, the outrage The Brown Bunny caused feels like a precursor to today. From the growing awareness of exploitation behind the scenes in the industry, to the rise of identity politics and the debates over representation, shock and offence in cinema is now less visceral, and more ideological.

For example, Tarantino was attacked for his use of the N-word in The Hateful Eight while the violence in his films has been seen as increasingly controversial, specifically that which is directed at women.

Meanwhile casting decisions regularly cause representation storms – from Emma Stone and Scarlett Johansson playing Asian characters in Aloha and Ghost in the Shell to Johansson originally being cast as a trans man in the now-postponed Rub & Tug.

And old movies continue to inspire new shocks from generation to generation. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective now seems transphobic because of the way it makes a trans female character a figure of monstrous humour, and Dumbo can’t be watched without balking at Disney’s decision to feature jive-talking crows – the leader of whom is called ‘Jim Crow’.

The concept of shock in cinema has changed – because it’s what audiences feel rather than what they see that governs what causes outrage. Which is why filmmakers may be perversely happy to see such an extreme reception for a film like The Painted Bird: at least it shows that there is still a more edifying way for cinema to shock audiences – through the visual image itself.

About the Creator

Monu Ella

And I know it's long gone and there was nothing else I could do

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.