What Clicker Games Say About Capitalism

How Idle Games Reflect Our Society

Video games are a unique art form—one must interact with the art directly, and the player can change outcomes, form relationships, or even abandon the main story in favor of side quests. Likewise, multiplayer games act as a conduit between us so that we connect with each other through competition or cooperation.

And then, there are clicker games.

What are clicker games?

Clicker games, also called idle games, or incremental games, have one goal—keep that currency number ticking up as high as possible. To do this, you have to continuously click (or tap, depending on the device) to increase your currency of choice. You then buy automated labor or machines that then perform that task for you, so you can make money even when not tapping. Then it slowly turns into an exercise in management, buying and selling your means of production so that you get more currency that you buy more workers and machines so that you get more money so that you buy more workers and machines so that you...

You get the idea. It's an endless cycle without a meaningful conclusion. Ultimately, a clicker game doesn't end. Rather, you stop playing it when it takes too long to buy the latest upgrade. Meanwhile, your long forgotten game continues to accrue currency.

These games shouldn't be fun. It has the entertainment value of continuously clicking a tally counter, and yet they're fairly popular, and there are many of them, and it seems as though the number of idle game apps increases as exponentially as the fake currency on all of them.

And yet, they have an addictive quality. I've sunk quite a few hours playing these games and mindlessly watching the numbers go up, up, up, up—sometimes to nonsensical numbers. I've been a multi-tredecillionaire, and I've also accumulated several "aa" worth of money (what is that?).

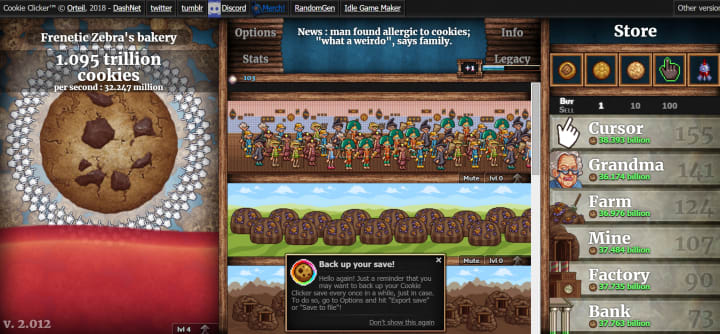

This genre started with the Cookie Clicker game, developed by Julien Thiennot, aka Orteil. As its name aptly implies, the game's gimmick is cookies. You click the giant cookie floating on the left of the screen (or, in the original version, in the middle) until you can buy cursors, grandmas, factories, mines, time machines, and portals—all of which let you make even more cookies without clicking. Once you've gone as far as you can, you can "ascend," or start from scratch, but with a multiplier that allows you to make more cookies faster than before.

Throughout the game, you get eerie messages about how your massive cookie empire is negatively affecting the universe. Eventually, your grandmas spark a worker's rebellion that cut into your profits while also implying that none of the grandmas you hired were actually human.

My current progress on my current cookie clicker game. I was tempted to start playing again...

How Clicker Games Emulate Capitalism

Cookie Clicker seems aware of its relation to the emergence and decay of capitalism and satirizes it in background clues, as explored further here. Likewise, some games have a similar tongue-in-cheek attitude—adventure makes games literally titled Capitalism and Communism to openly satirize these economic ideologies through their clicker games.

Some games do try to make a point with their structure. A Dark Room might be the only one that really grapples with the issue of purchasing infinite labor, and it's not even really a clicker game, just one that necessitates collecting resources. In one very important turn, the player character calls the workers, weary people who find shelter in huts and automate the collection of certain items, slaves. From then on, the game refers to them as slaves, and the developer admits that many people were so offended they couldn't continue playing after that turn. There's also a "no slaves" alternate ending if you choose not to build huts in the game.

However, as Poe's Law is inevitable, sometimes these games seem to take on the aesthetic of late capitalism without really stopping to examine what's at play here. For instance, there's the iOS app Sweatshop, which appears to just be a clicker game of a clothing sweatshop. Other idle games, like Make More, encourage players to "be the boss" of a factory where workers sit and just make product after product. The boss in the background angrily pounds his fists in the meanwhile. Even EggInc, a game I personally love, titles one of its research options "Smash Unions" to get cheaper trucks.

So what exactly is going on?

It's bizarre to see images like that pop up in your app advertisements. Supposedly, the average person knows that working in a sweatshop or factory with little to no rights as a worker is a horrific experience. We seem glad that we aren't 19th-century laborers working in desolate conditions as long as possible for as little as possible, and yet our games start harkening back to that era.

So why?

One factor is the shrinking middle class in America. Economic wellbeing and job security seem like mere dreams to many families. Retail, fast food service, and warehouse jobs are infamous for their less-than-stellar conditions, and many owners seem more interested in the greatest amount of stuff created without much regard for the labor they purchase. With Jeff Bezos joking that he can't figure out what to do with his billions of dollars while his underpaid warehouse workers are accused of "wage theft" for simply going to the bathroom, it's easy to understand that we are not so far removed from that reality, and it bleeds out into our entertainment.

In these games, the player also acts as the capitalist—they are the factory owner. Being put in a position of power, especially in a situation you feel relatively helpless in reality, can be cathartic. Also, having a fantasy world where you have unlimited fantasy dollars? It works as a nice escape from reality.

However, they also show a darker side of late-stage capitalism. We watch the numbers on our idle game(s) go up and up and up, but eventually, we all leave the game. It's the only way to "finish," after all—leave it to rot, quietly making more money that collects dust.

After a while, making nonsensical amounts of money is no longer fun anymore and we, the factory owners and entrepreneurs who created this system, just leave it behind effortlessly. Meanwhile, the bits of code that make up our labor force are left behind to deal with our consequences.

Now, I highly doubt that real-life billionaires would just leave their money behind and "leave capitalism," because that doesn't make any sense. However, we have heard of Wal-Marts slowly monopolizing local markets, then devastating the local economy when the superstore closes down.

What does this mean?

Ultimately, these banal, trivial game apps are nothing but a lens into many of our banal, trivial lives. Art imitates life. The only real difference is an attempt to position ourselves in the seat of power.

That may mark a problem in the way we think about these issues. It's like the American Dream—very deep in U.S. mythology is the belief that hard work and a little entrepreneurship can get you the white picket fence and the slice of life you always dreamed of. Even as that dream drifts further and further away from our reality, we still cling to it somehow, and indeed have perverted it—"making it" now entails controlling and exploiting a large amount of your workforce.

References

Jeff Bezos just made a lot of people mad by admitting how he’s spending his massive fortune

Jeff Bezos thinks his fortune is best spent in space

About the Creator

Haley Booker-Lauridson

Haley is a passionate freelance writer who enjoys exploring a multitude of topics, from culture to education.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.