Vikings and the United States of America

How the Vikings set the stage for the Greatest Superpower in the World

Two hundred and thirty-three years ago, in 1788, the United States Constitution was ratified into law and the United States of America was truly born. In the centuries since, our most cherished document has been the blueprint for countless constitutions written throughout the world, as autocratic rule has lost its luster among Earth’s people. The ratification of the US Constitution is considered a watershed moment in the modern history of the world. Indeed, history is rife with watershed moments. Leonidas standing against Xerxes and allowing Greek culture to influence the western world. Julius Caesar casting his die along the banks of the Rubicon, inciting the great Roman Civil War. The Han Dynasty of Ancient China pushing the Huns out of the Asian steppes, cultivating the unrest that led to the fall of the Roman Empire. Pope Alexander IV urging Spain and Portugal to sign the Treaty of Torsedillas, splitting the known world between the two nations. Gavrilo Princep assassinating Archduke Ferdinand, setting off World War I. Ronald Reagan spending the Soviet Union into near bankruptcy, ending the most brutal authoritarian regime of the modern world. But each one of those moments have origins that are much less known because the connections aren’t readily apparent. Such is the connection to be discussed here… How are the Vikings of old responsible for the eventual ratification of the United States Constitution?

To answer that question, we must travel to the Scandinavia of 13 centuries ago. It is theorized that nobles in Scandinavia, in the 7th and 8th centuries, enjoyed the right of polygamy. So many wives would these nobles have that there was a shortage of women for the general population of men. So, men being men, they resorted to more and more risky behavior to court those not yet married. They also banded together and tried to find women from outside their lands. Thus was born the Vikings, raiding and pillaging the coastlines of Europe.

Warning to the reader: what follows is a concise, yet potentially dry bit of material to set up the watershed moment. The confusion of Medieval European politics is complex and requires, at times, much explanation. Here we go…

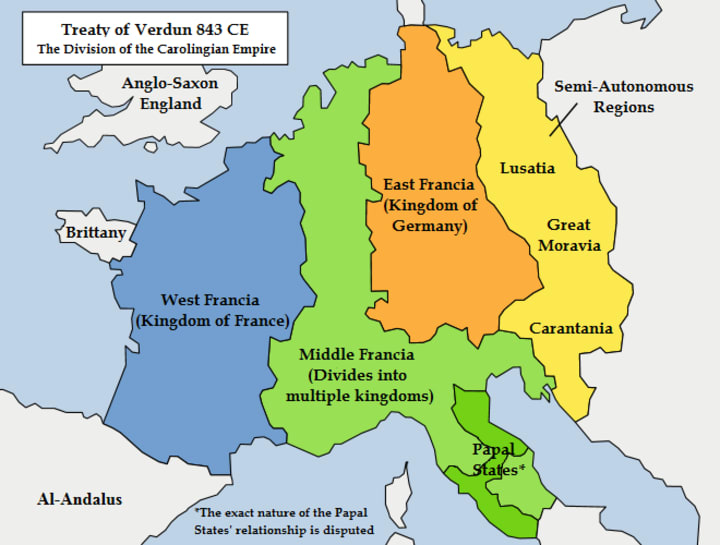

West Francia was one of three kingdoms in Europe that resulted from the Treaty of Verdun, in which the grandsons of Charles the Great [Carolus Magnus in Latin, and more commonly known as Charlemagne] divvied up his Carolingian Empire. West Francia was led by Charles III, or Charles the Simple; ‘simple’ referring to the idea that Charles was straightforward, not simple-minded, though his direct control over the kingdom’s territories was not 100% solid. One of his cities was Chartres, which came under siege by Rollo, a Viking leader, in 911. Even as the siege failed in the month of July, Charles, using forward thinking, signed a treaty with Rollo which granted him lands and title from the river Epte north to the English Channel. In return for the lands and title, Rollo was charged with paying homage to the Francian king and defending the kingdom from further Viking incursions. Rollo had become the first Duke of Normandy, and little did he know how his progeny would shape the world.

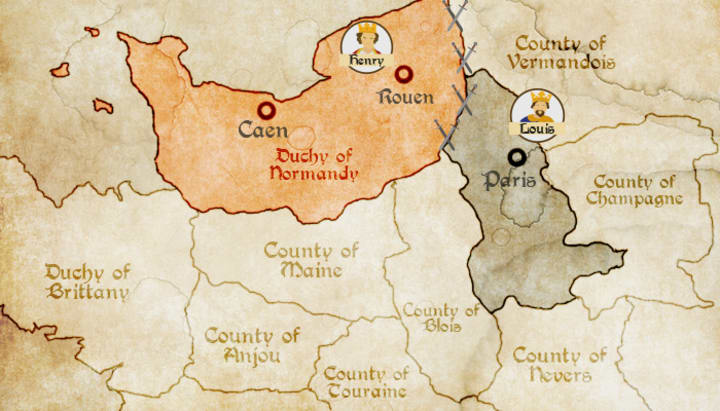

The next seven decades saw the power of the Duchy of Normandy increase, as did its influence. In 980, that power was solidified as the Duke of Normandy aided Hugh Capet onto the French throne. Meanwhile, across the channel in Anglo-Saxon England, Æthelred the Unready ascended the throne in 978, at the age of 12. His kingship was immediately under attack, as the incursions from Danes became fast and furious. He also dealt with Viking raids coming from Normandy itself. As was common in Medieval times, and the fact that Æthelred’s first wife had died in 1002, the English king married Emma of Normandy, daughter of Richard the Fearless.

Æthelred and Emma were forced to leave England in 1013 as a result of the ongoing conflict with the Danes. They returned in 1014, but then the English king was killed, and his eldest son from his first marriage, Edmund Ironside, took the throne. That only lasted until 1016, when he died, and the Danish king, Cnut, took the throne of England for the next 19 years. Finally, Emma’s eldest son, Edward the Confessor, took the throne. But here now was a medieval conundrum, as the English king was, at once, on equal footing with the French king, but was also forced to pay homage to the French king as the Duke of Normandy. It was not an entirely untoward situation for the English king, but for future kings it would become a serious issue. Edward reigned until January of 1066, another watershed moment and a year that would change the world.

Edward died childless, and the throne of England, upon his death, went to his brother-in-law, Harold II. As Harold was not within the bloodline of the Dukes of Normandy, and, it is said, that it was encouraged by the late king, William, great-great-great grandson of Rollo and Duke of Normandy, chose the autumn of that year to invade England. As it was, the Danes also chose then to invade northern England. By the end of September 1066, King Harold was dead, and the Anglo-Saxons and the Danes were both defeated. William the Conqueror had begun the Norman Conquest, and he completed it twenty years later. What would follow would be nearly four centuries of constant warfare between the kings of England and France over continental holdings.

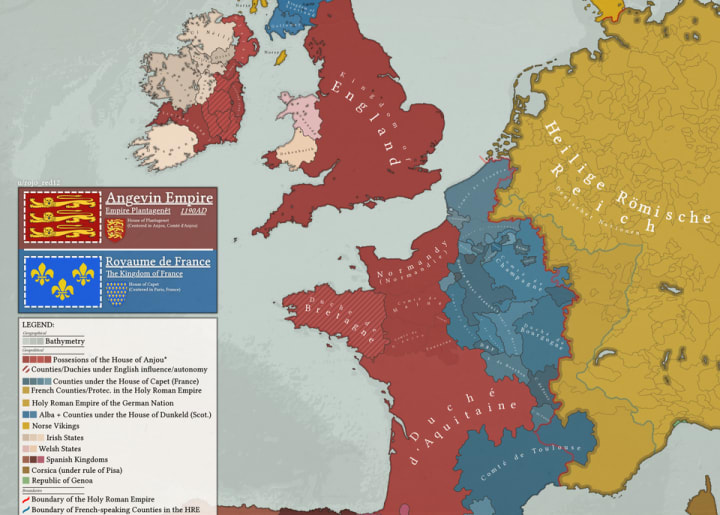

Henry II ascended the English throne in 1154, following the near 20-year “Anarchy”, or state of civil war, on the English isle. Henry’s bloodline placed him in the Plantagenet family, and when he took the kingship, he also inherited the lands of Anjou and Maine from his father, Geoffrey, and Normandy from his mother, Matilda. His wife, Eleanor, also happened to be the heiress of the land of Aquitaine, thereby giving the English king more French territorial control than the French king. Not long after, King Henry placed one of his sons on the throne of Brittany, the western peninsula of modern-day France. Brittany, at the time, was an independent Norse kingdom. Historically, these tracts of English-controlled land became known as the Angevin Empire. Another forty years on, Henry’s youngest son, John, succeeded his uncle, Richard the Lionheart, to the throne.

By that time, John’s nephew, Arthur, held the throne of Brittany, and he was a close ally of Phillip II, King of France. Also related to the ruling Plantagenet family was Otto IV, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He ascended to his throne in 1197, following the death of Henry IV of the Hohenstaufen family, and with the backing of Pope Innocent III. As you can see, the bloodlines and allegiances of the Middle Ages were complicated.

These complications, however, would provide the connection we seek from the introduction.

King John would go to war with his nephew, the King of Brittany, and though he would be victorious over his nephew, King Phillip II of France would reaffirm the relationship between the French throne and the Duchy of Normandy, aka ‘suzerainty’. Then, in 1202, the big mistake was made by King John. In Aquitaine, there lived a woman known as Isabella of Angoulême, of the Lusignan family. The English king had chosen her to be his bride, not knowing that the lady was already betrothed to another. This episode angered the Lusignan family and war broke out. Phillip II used this to his advantage, and, with the mysterious death of Arthur, King of Brittany, the French king was able to reestablish French control over Brittany, Normandy, Anjou, and Maine. King John would make an unsuccessful attempt to retake those lands four years later.

Despite the Hohenstaufen family’s loss of the Holy Roman Imperial crown to Otto IV, the family still held kingship over lands on the Italian peninsula and Sicily, south of the Papal States. Two years after King John’s failed attempt at reclaiming the Angevin Empire, the head of the Hohenstaufen family, Philip, Duke of Swabia, was assassinated. In a bold move, the Holy Roman Emperor decided to try to end the Hohenstaufen family for good and set out to conquer the South Italian throne. Not only did this anger German princes still loyal to the Hohenstaufen family, but it also resulted in Otto’s excommunication from the Roman Catholic Church. Rebellion was fomented among the princes, and in 1211 they chose to name Frederick II, son of the previous emperor, Henry IV, to the imperial throne. The Holy Roman Empire was on the cusp of civil war.

Oddly enough, around the same time of Frederick II’s naming, the English king was excommunicated from the church. This was the pot that boiled over, as the papacy was indignant over John’s nominee for the Archbishop of Canterbury. But even though John was reinstated in 1213, King Philip II of France saw his chance. The papacy was unhappy with both England and the Holy Roman Empire, and he tried to use that as a means to invade England. The proverbial jig, however, was up, as Philip’s naval forces never made it to England, for the Earl of Salisbury had sailed his own navy to the port of Demme and defeated them handily.

For all that preamble, three centuries after the Vikings settled Normandy, we have finally arrived at the watershed moment. King John and Emperor Otto had formed an alliance, with five high ranking Counts and Dukes behind them, and they believed that now was the time to strike King Philip and end the growing French threat. John’s plan was to split the French forces, and so he sailed south to Aquitaine in an effort to draw significant attention from Philip, making him fearful of a two-front war. Otto would then send his forces headlong into France, their goal to be Paris.

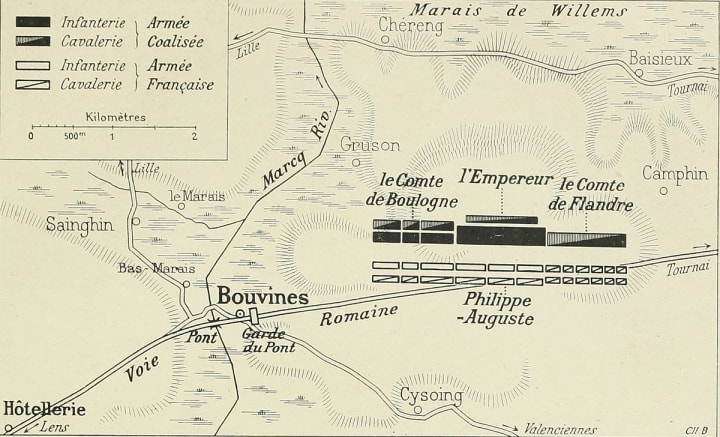

John’s feint worked, but after three days of posturing, he had his forces retreat deeper into Aquitaine, allowing the French forces to no longer fear attack and make their way back northward to the king. Otto’s army rushed into France and made it as far as the town of Bouvines. Now, Philip did not expect the battle to take place when it did, for it was commonly forbidden to fight on a Sunday. But Otto had no care for that and marched on to catch the French forces. Philip’s scouts were aware of this and sent word to the king of the impending attack. To Philip’s luck, the enemy was forced to travel in long lines along the old Roman roads, and so it took time and effort to form up for battle, leaving the soldiers more fatigued than they should have been. Coupled with a less-than-stellar plan of attack, the Battle of Bouvines became a great victory for King Philip II and laid the groundwork for the “divine right of kings” that would guide the French monarchy for the next 575 years.

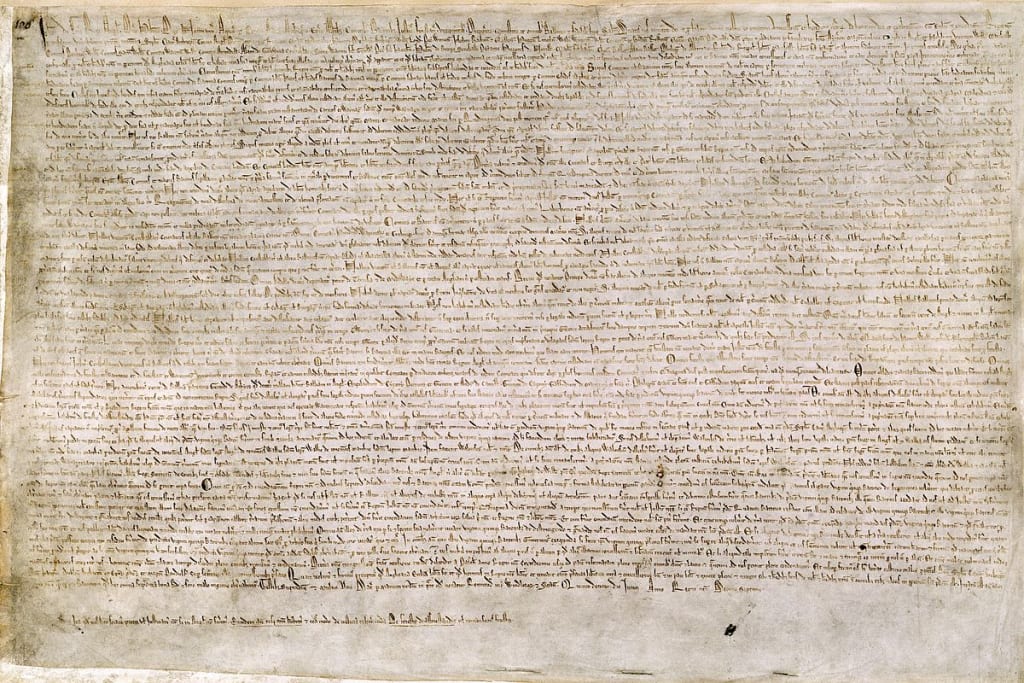

For King John, on the other hand, things would not bear out so well. The barons of England were furious at the humiliating defeat, and they felt that they deserved more of a voice in the policies and actions of the kingdom. On June 15th, 1215, at Runneymede, King John signed the Magna Carta. This document is basis of all common law and was the beginning of the recognition of the rights of the governed. Over the next four centuries, English kings would see their power dwindle as the power of the English Parliament grew, and representation of more and more subjects was demanded. The 16th century would see the beginning of the Protestant Reformation and the establishment of the Anglican Church. The 17th century would know little peace, either on Mainland Europe or the British Isles. The Thirty Years’ War on continental Europe would see the redrawing of the political map, making it look more like our current map; and the English Civil War that covered most of the mid-century would see the rise of names like Oliver Cromwell, and would culminate in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, in which the British Empire officially became a Constitutional Monarchy. A century later, the world would see the birth of a new nation, one devoid of a monarch, based on a government established with the consent of the governed.

So, there you have it… Eight hundred and seventy-seven years from the establishment of Viking-controlled Normandy by men seeking wives to the establishment of the greatest constitutional republic the world has ever known. Consider, if you will, the idea that 7th and 8th century Scandinavian nobles didn’t have the greed for wives. Would the world have known the existence of raiding and pillaging Vikings? Perhaps there never would have been a Duchy of Normandy, or a Norman Conquest of England? Perhaps the Anglo-Saxons would’ve have been defeated by the Danes, and the British Empire would have been the Danish Empire? There would have been no Magna Carta, perhaps no Protestant Reformation, no Glorious Revolution, and no American Revolution. What would the world look like today?

About the Creator

Anthony Stauffer

Husband, Father, Technician, US Navy Veteran, Aspiring Writer

After 3 Decades of Writing, It's All Starting to Come Together

Use this link, Profile Table of Contents, to access my stories.

Use this link, Prime: The Novel, to access my novel.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.