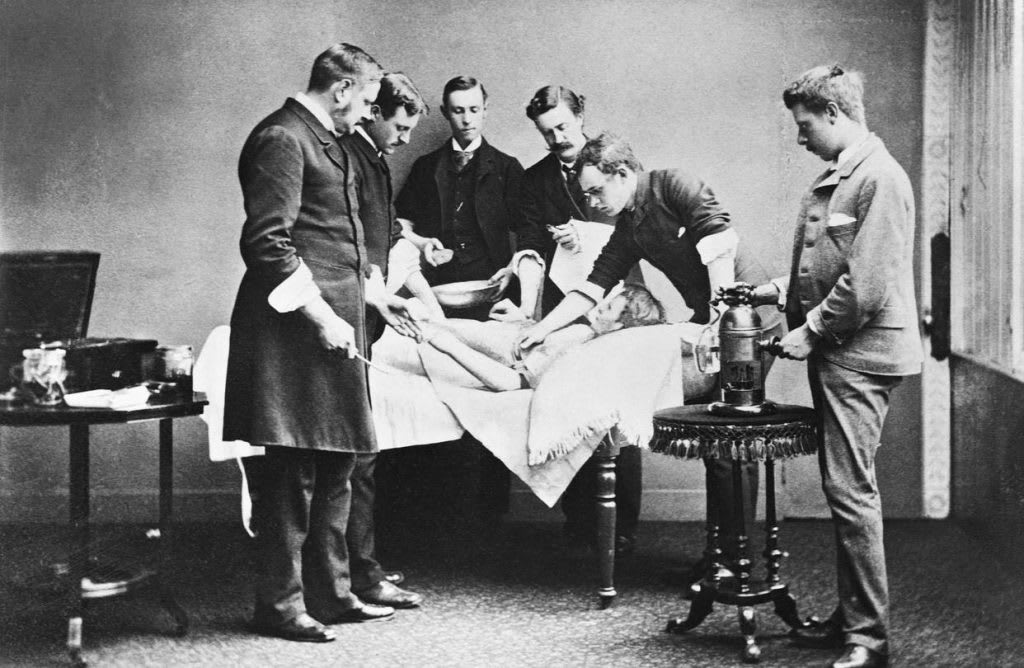

VICTORIAN SURGERY WAS OFTEN A DEATH SENTENCE

Many patients died of shock because of the absolute agony of surgery

VICTORIAN SURGERY WAS OFTEN A DEATH SENTENCE

From the first cut to the severed limb dropping into a box of sawdust, surgeon Robert Liston could remove a leg in 25 seconds. His operations at University College Hospital in London in the early 1840s were notorious for their speed and intensity.

In some hospitals one in four patients died because of surgery, with infection the biggest killer. Entering hospital was the last resort. That’s because, far from making you better, going under the surgeon’s knife might have killed you. The fatality rates for the Victorian-era surgery were horrifying.

Many patients died of shock because of the absolute agony of surgery, suffering heart attacks on the operating table. Some London hospitals even billed patients booked in for surgery for their own burial. On the plus side, they were given a full refund if they beat the odds and made it off the operating table alive!

Instead of being a warning of infection, pus was looked upon as a good thing and proof a wound was healing. These days, you don’t need a medical degree to know pus is a sign of infection. Back in the 19th century, however, some surgeons referred to it as the ‘laudable pus’ and regarded a seeping wound with approval, confident they had done a good job.

Surgeons also took a perverse pride in their bloodied aprons – the dirtier the better. In 1902, Sir Frederick Treves saved King Edward VII’s life, but even Sir Frederick had a questionable attitude to cleanliness and hygiene. For much of the 19th century, surgeons like him took pride in their bloody gowns and smocks they wore over their everyday clothes while in the theatre. A clean gown was the sign of an idle surgeon, while an apron covered in the blood, guts and pus was the sign of a busy man. Unsurprisingly, such an approach led to many patients catching infections and dying.

Early attempts at putting patients to sleep were often unsuccessful – patients sometimes woke up or never woke up at all. Before modern anaesthetics, surgeons used a variety of methods to reduce a patient’s pain. Most times, they simply gave the patient large doses of gin or whisky, hoping they would pass out from drunkenness. Other surgeons preferred to try a range of herbs or even narcotics, such as opium imported from the East. While alcohol was usually ineffective, opiates sometimes were too effective – indeed, instances of patients dying from a drug’s overdose having only gone into hospital to have a limb amputated were shockingly commonplace.

Many patients simply bled to death on the operating table, though burning wounds with red-hot irons stopped this. Amputations were far more commonplace back in the 19th century than they are today. Simply, if a fractured bone pierced the skin, the chances are that whole limb would need to be chopped off. The surgery was brutal, painful and very dangerous, especially since the odds of bleeding to death were so high.

The most common method to stop a patient bleeding to death was to cauterise the stump of a limb. They would toss the discarded arm or leg into a bucket of sawdust, usually right next to the patient, who would get a gory close-up view of their own amputated limb. Then the surgeon would plunge a red-hot iron into the stump, burning the veins and arteries, closing them up for good. This would have been agony for the patient, especially if they had been given zero pain relief. Accounts from Victorian-era hospitals often remarked on the disgusting smell of burned human flesh.

It was only towards the very end of the Victorian era surgeons became respected medical professionals. Prior to this, they were seen more as butchers than as learned physicians. However, that doesn’t mean that all Victorian-era surgeons were professionally competent. They limited entry to the best universities and colleges to the upper classes. Connections and family wealth were often more important than academic ability. As a result, many of the surgeons were attracted to the profession by the blood and guts nature of the work, rather than by the academic challenge.

About the Creator

Paul Asling

I share a special love for London, both new and old. I began writing fiction at 40, with most of my books and stories set in London.

MY WRITING WILL MAKE YOU LAUGH, CRY, AND HAVE YOU GRIPPED THROUGHOUT.

paulaslingauthor.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.