TRAGEDY ON THE THAMES

Of the 700 believed to have been on board, at least 650 perished

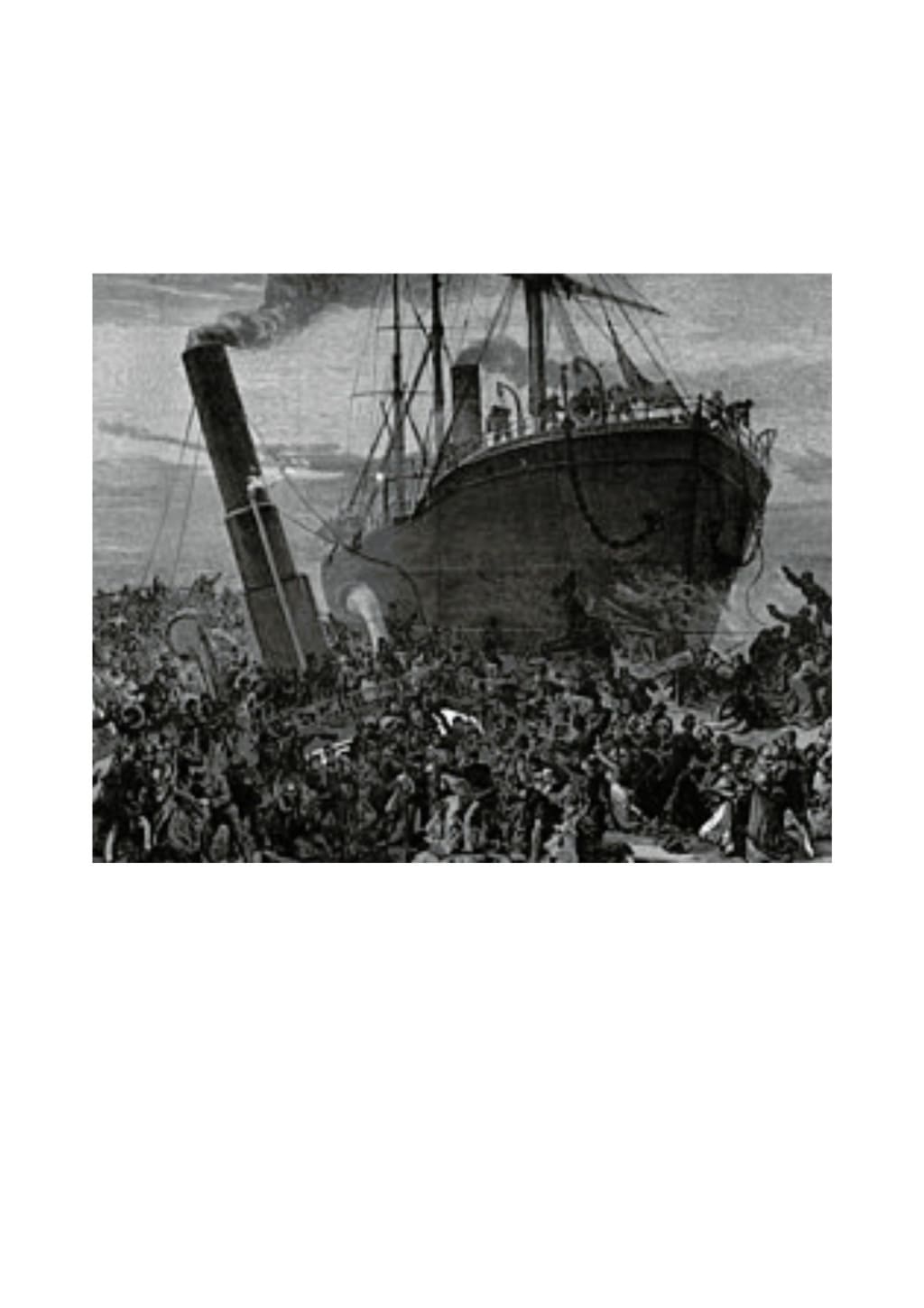

In scenes of indescribable panic and confusion, men, women, and children fought to escape the sinking vessel, but it was hopeless. Of the 700 believed to have been on board, at least 650 perished.

On Tuesday 3rd September 1878, the Princess Alice steamer was making her way up the Thames on her return journey from Sheerness to London. The weather had been fine and her passengers had enjoyed a day’s pleasure trip to the Kent coast.

The Princess Alice was shattered like an eggshell and cut in half by the knife-edge bows of a sea-going outward-bound coal boat. In a split second, the 700 passengers were at the mercy of the river.

There could have been little thought of danger in the minds of the 700 day-trippers who boarded Princess Alice on a fine autumn morning. A day’s river trip to the coast was the only holiday many London kids got in those days. Everything seemed OK, even the weather. The steamer was making what was billed as a Moonlight Trip from Swan Pier, near London Bridge, downstream to Sheerness, Kent, and back.

The weather was sunny, and the passengers were excited as the pleasure steamer set off from London and headed out to catch the summer sun and the fresh sea air of Sheerness.

The cost of the trip was around two shillings, depending on which stop the passengers travelled to. The boat left London about 11.00 in the morning, heading downstream for Gravesend, a distance of thirty-one miles, and from there, on to Sheerness. The trip to Gravesend usually took around ninety minutes, and once there, many of the day-trippers went on to one or the other of the attractions. For Gravesend was becoming a popular town in the nineteenth century.

The steamer pulled out of Gravesend and headed back up the Thames at just after 6.00 pm. The passengers who had paid two shillings for the day trip probably felt that their money was well spent. The weather had been kind, although by 7.40 pm, as the boat approached Woolwich pier, there was an almighty crash. The passengers then heard grazing and scraping at the side of the vessel, then a sudden stop, and then another terrible crash of shivering and splintering timbers. Amid the confusion and screams of the passengers, water was rushing in below and the boat began to sink.

The day-trippers then saw the bows of the massive ship towering above as high as the walls of a castle. The Bywell Castle was a newly repainted steam collier of 890 tons bound for Newcastle to pick up a cargo of coal for Alexandria, Egypt.

In the ensuing chaos, some passengers jumped into the water, others attempted to climb aboard the Bywell Castle, and a great number were trapped below decks when the two boats collided. A few were clinging onto the chain at the bows, but what was one chain for seven hundred people, many of them women and children, all crowding and trampling one another in a boat which was doomed to sink to the bottom of the Thames. The shrieks, prayers, and wails of helpless agony were heartrending.

The Princess Alice didn’t stand a chance against a ship four times her size. Within minutes, she sank to the bottom of the river. In scenes of indescribable panic and confusion, men, women, and children fought to escape the sinking vessel. But it was hopeless. Of the 700 believed to have been on board, at least 650 have perished.

There were only twelve lifebuoys on board and a couple of lifeboats, but the accident took place at such speed it was impossible to organise their use. They rescued about 130 people from the collision, but many died later from ingesting the water. Princess Alice sank near to where London’s sewage pumping stations were sited. The twice-daily release of over 75 million gallons of raw stinking sewage from the outfalls Abbey Mills, at Barking, and the Crossness Pumping Station had occurred just one hour before the collision.

In a letter to The Times shortly after the collision, a chemist described the outflow as two columns of fermenting sewage, hissing like soda-water, with gases that were so black the water was stained for many miles.

For weeks, decaying bodies were washed up on the riverbank. The tragedy, now largely forgotten, dominated newspaper headlines for weeks and led to changes to the shipping industry.

About the Creator

Paul Asling

I share a special love for London, both new and old. I began writing fiction at 40, with most of my books and stories set in London.

MY WRITING WILL MAKE YOU LAUGH, CRY, AND HAVE YOU GRIPPED THROUGHOUT.

paulaslingauthor.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.