The True Story of Arnold Paole, Vampire of Meduegna, Serbia

A vampiric plague in Serbia during the early 1700s began with Arnold Paole — and it’s all in official government records.

For many, the word “vampire” conjures images of high-collared capes and slicked-back hair.

Or a trickle of blood from the mouth of a shirtless come-hither model.

Or a lounging seductress sipping blood from a wine glass.

Though, it wasn’t always that way. Vampire fiction has changed over time, growing less ghastly as the years go on. I know it’s hard to believe now with all of the stories of romance and reluctant hero vampires out there and sexy sparkling daylight walkers, but vampires used to be absolutely stunningly terrifying.

The old world terror people felt from the very notion of vampires wasn’t like the “terror” you feel when you’re about to head home from a party and realize your phone is missing, you never put a password on your lock screen, and you’ve got some questionable search history in your web browser. No, not that kind of terror. Vampires used to terrify people in a visceral way that we, modern people with access to marvels like flashlights and WebMD, may never truly understand.

Let’s look back at a part of the world in the 1700s, a time and place full of unknowable horrific things that could kill you, your family, or maybe your entire village at every turn. It was a place, unlike today, where stories of vampires weren’t entirely fictional, and the true story of a man named Arnold Paole, vampire of Meduegna, can be found in official government records.

Serbia in the 1700s

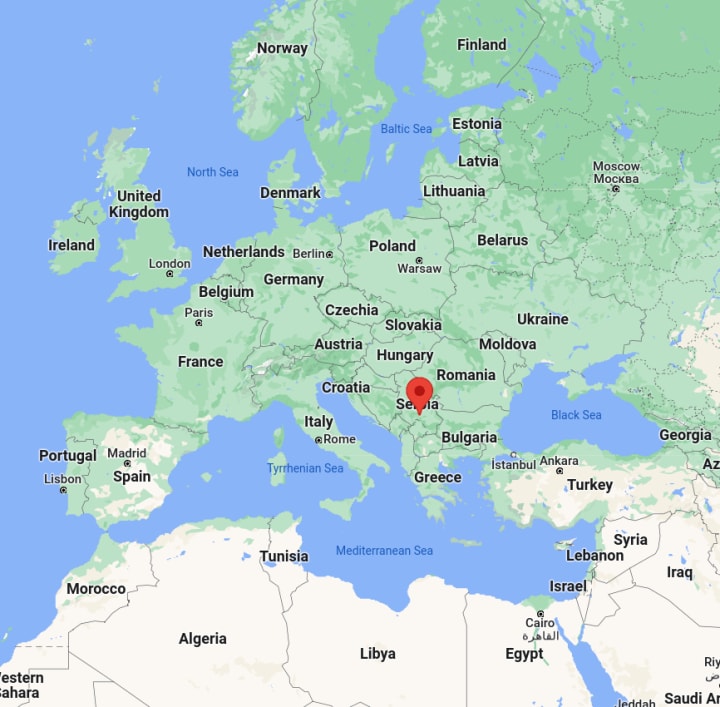

If you’re like me, you were never in Serbia during the 1700s, so here’s A Quick History of Serbia to help you understand the country’s history. In modern-day central Serbia, there’s a town called Trstenik.

Trstenik is still relatively small, with a population of around 15,000 people and just over 40,000 if you also count the surrounding area. A few hundred years ago, there was a village called Meduegna where frightening and mysterious events were blamed on vampires.

The village of Meduegna, in fact, may actually be modern-day Medveđa in the Jablanica District of southern Serbia. Or possibly another location near Belgrade. There appears to be a bit of confusion surrounding the location in the English-speaking world, but I found some references from Serbian citizens who say the events I’m about to describe occurred in modern-day Medveđa. Medveđa, Serbia, has even fewer people than the area of Trstenik. The population of Medveđa is around 3,000, or 7,500 counting the surrounding area.

So, until I can find a way to verify the exact location with irrefutable proof, I thought I’d mention all three possibilities.

In any case, as you might imagine, this part of the world in the 1700s was sparsely populated and full of dangerous wildlife like brown bears, wild boars, and grey wolves — the national animal of Serbia. Nature was beautiful, hostile, and brutal to humans. Living in a small village was scary; news traveled incredibly slowly, if at all.

In 1718, the Habsburg Monarchy annexed most of Serbia, which previously was part of the Ottoman Empire. The area remained in Austrian control until 1739, with the signing of the Treaty of Belgrade, when the Turks took control. In those twenty years, the boundaries were under direct military rule from Vienna. Due to the devastation from the Austrian-Ottoman wars, the region was in poor condition, with a small nomadic population mainly focused on cattle instead of other types of agriculture. Austria, seeking economic development, recruited militiamen known as “hajduks” to protect the borders and serve in the military during wartimes. In exchange for border protection and military service, the hajduks were promised unalienable lots of land. Many answered the call and joined or formed communities to claim their new land, including a hajduk named Arnold Paole.

The Strange Events Surrounding Arnold Paole

Arnold Paole, or Arnont Paule (aka Арнаут Павле or Arnaut Pavle) as he was called in the original government records, sought to claim land and moved to Meduegna, Serbia, in the early 1700s. Evidently, Arnold Paole had previously been plagued by vampire attacks before moving to Meduegna, in a place called Gossowa (possibly modern-day Kosovo). Arnold Paole rid himself of the vampire by finding the vampire’s grave, eating soil from it, and smearing the vampire’s blood on himself. I think he likely dug up the grave to do this.

In 1725, Arnold Paole fell from a haywagon, broke his neck, and died. He was buried, and the town moved on, everyone doing their best to survive the harsh conditions and wild lands. Arnold Paole, however, didn’t stay in the ground where the village buried him. Within about three weeks, four frightened villagers proclaimed that Arnold Paole visited them, harassed them — plagued them. All four villagers then died. No accidents, like falls from haywagons, just — dead.

The villagers remembered Arnold Paole talking about how he’d been plagued by a vampire in Gossowa and how he’d rid himself of it. After some discussion, the village decided it best to take a look for themselves, and so forty days after Arnold Paole died, his grave was opened. Inside was Arnold Paole’s corpse — undecomposed. His body wasn’t showing the usual signs of death and subsequent burial. No shriveling and fresh blood flowed from his eyes, nose, mouth, and ears. The nails on his hands and feet, the hair on his head, and his beard had all grown noticeably. Arnold Paole’s shirt, his shroud, and the inside of the coffin were covered with blood.

A vampire.

A wooden stake was driven directly through his heart, which resulted in Arnold Paole shrieking, groaning, and bleeding. A vampire, indeed. The villagers cut off his head, then burned his entire body. Afterward, they proceeded to disinter the four victims of Arnold Paole and give them the same treatment to prevent them from becoming vampires.

That spelled the end of Arnold Paole and the end of the vampires in Meduegna. Or so the village thought. Five years later, in 1731, seventeen people fell ill and died in the period of a few weeks. Reports vary somewhat, but the victims spanned from 10 years old to around 70. After becoming ill, they complained of stabbing sensations in their sides, chest pain, fever, and involuntary jerks of their limbs. One of the girls who died, a girl named Stanoska, became terribly ill the same night she woke up screaming that a boy who suddenly and mysteriously died weeks before came to her in her bed and tried to strangle her.

The villagers reported the deaths to the Austrian military commander in charge of the administration of the area and, fearing a possible epidemic, sent for an infectious disease specialist, Imperial Contagions-Medicus Glaser, who was already stationed at the nearby town of Paraćin. Glaser visited Meduegna and investigated but failed to find any signs of infectious diseases and blamed malnutrition. The villagers had none of this and insisted it wasn’t malnutrition but vampires; some even threatened to abandon the village for their own safety unless the authorities found and disposed of the vampires plaguing them. Glaser agreed to exhume some of the bodies, and what he found shocked him. Some of the recently deceased were decomposed, but others who had died earlier had not deteriorated and had blood in and around their mouths — like Arnold Paole. Unsure of what to make of this, Glaser reported back to the Supreme Command in Belgrade, recommending that the military execute the vampires as the villagers requested.

Word of the strange events reached Vienna, and the Austrian Emperor ordered an inquiry into the deaths. Regimental Field Surgeon Johannes Flückinger, along with two officers and two other military surgeons, were sent to Meduegnes to learn more about what happened. Shortly after Flückinger arrived, two more people died, and the village began to disinter the earlier victims. They found the bodies in the same state they had discovered Arnold Paole after digging him up. Some even had fresh blood in their organs and appeared younger than when they died. In the official report, Flückinger stated that the bodies were “das Vampyrenstand,” meaning “in vampiric condition.”

After some investigation, the villagers found that the first victims to die during this period all had something in common: Arnold Paole. In addition to the vampire Arnold Paole killing four men, he also killed a few sheep. In such a harsh environment, some villagers didn’t want the meat to go to waste. So, they ate it. One of the women, Stana, even smeared Arnold Paole’s blood on herself to protect herself in the same way that Arnold Paole said he did to defend himself against a vampire plaguing him. Stana was one of the first to die.

Flückinger ordered everyone recently deceased to be dug up. Forty bodies were disinterred; seventeen were in a preserved state similar to Arnold Paole. All seventeen were staked, beheaded, and burned — the decomposed bodies were laid back to rest in their graves.

The mysterious deaths suddenly stopped.

Flückinger wrote up his findings in an official government report titled “Visum et Repertum” (Seen and Discovered) from 1732. The report was presented to the Austrian Emperor, becoming a best seller, with circulation all over Europe. You can read it in its entirety here, translated to English: Visum et Repertum (1732).

The Catholic Church learned of the events and got involved due to the mutilation of bodies. According to their beliefs, the bodies of Christians awaiting resurrection were desecrated, rendering them incapable of going to heaven. At the request of Cardinal Schtrattembrach, the bishop of Olmutz, a specialist from the Catholic Church got involved — Giuseppe Davanzati, an archbishop of the Roman Catholic Church and vampirologist. Davanzati spent years analyzing the problem of vampires and concluded that it was all the result of human fantasy, likely of demonic origin. He urged the Catholic Church to leave the bodies undisturbed and to direct their attention to the people reporting vampirism to give them spiritual guidance.

Meanwhile, Antoine Augustin Calmet, a French Benedictine monk, known for his “Dissertations sur les apparitions des anges, des démons et des esprits, et sur les revenants et vampires de Hongrie, de Bohême, de Moravie et de Silésie” or “Dissertations on the Apparitions of Spirits and on the Vampires or Revenants of Hungary, Moravia, and Silesia,” came to a very different conclusion than Davanzati. Calmet called upon scholars, theologians, and doctors to give the subject of vampires serious study and consideration. He argued that the bodies were animated by demonic forces.

The controversy raged on until Empress Maria Theresa of Austria (Marie Antoinette’s mother) sent her personal physician, Gerard van Swieten, to investigate the various claims of vampires. Gerard van Swieten concluded that vampires did not exist. The Empress passed laws that prohibited opening graves or desecrating bodies.

Vampires everywhere rejoiced.

Plausible Theories That Don’t Involve Vampires

Premature burial? Catalepsy? Something in the soil? Perhaps the shrieks when the bodies were staked resulted from trapped gas? An as-of-yet unknown disease? Maybe even rabies? Porphyria?

All of this is well and good, I suppose — if you believe in this “science” stuff. But, honestly, with all the complicated string of reasoning necessary to put a plausible theory together with no loopholes, isn’t “vampires” a much simple explanation? No one has any proof of precisely what caused all the deaths. But, if you believe vampires exist, it is a simple explanation for the strange events surrounding Arnold Paole.

Today, if the same thing happened in your neighborhood and you explained it all away with science, how many of your neighbors would be checking under their beds and in their closets and triple-checking their deadbolts before bed? Would you be able to wake up to a bump in the night and simply roll over and go back to sleep? Or, would you stare wide-eyed into the darkness, holding your breath, wondering…what was that noise?

Relevant & Related

- The Family of the Vourdalak — is a gothic novella by Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy about vampires in Serbia.

- Check out “Leptirica,” a Yugoslavian Horror Movie That is Scary, Even for Today’s Standards

- A film titled “Vampir” was released in 2021 about vampirism in a small town in Serbia. You can see the movie trailer here: Vampir (2021) — Official Trailer.

I’ve written more about the history of vampires; here are a few:

- A penny dreadful that set the tropes for modern-day vampires: Varney the Vampire; or, the Feast of Blood

- Victorian-era fiction that came before Bram Stoker’s Dracula and features a lesbian vampire: Carmilla by Sheridan Le Fanu

- Terrifying encounters with The Vrykolakas of Greek Folklore

~

Originally published in my weekly newsletter Into Horror History — every week I explore the history and lore of horror, from influential creators to obscure events. Cryptids, ghosts, folklore, books, music, movies, strange phenomena, urban legends, psychology, and creepy mysteries.

About the Creator

J.A. Hernandez

J.A. Hernandez enjoys horror, playing with cats, and hiding indoors away from the sun. Also, books. So many books—you wouldn't believe.

He runs a weekly newsletter called Into Horror History and writes fiction.

https://www.jahernandez.com

Comments (1)

Very interesting