The Man Who Died First

The story of John Torrington, leading stoker on the Franklin Expedition

On December 10, 1826—195 years ago today—a young boy named John Torrington was baptized in Manchester. We don’t know his birthdate. He may have been born in 1826, along with his sister, Esther, who was baptized the same day as him. Or he may have been born in 1825, as some records suggest. He came from a working-class family, one where not everyone could read or write, and there are few records of him at all. His father was William, a coach man, and his mother was Sarah, whose maiden name, Shaw, became John’s middle name. He was an ordinary boy, one of many who were baptized that day. His name sits at the bottom of the page of the parish baptism registry, easily missed, easily forgotten.

His name wasn't forgotten, though, but not because of what he did in life. We remember him because he died.

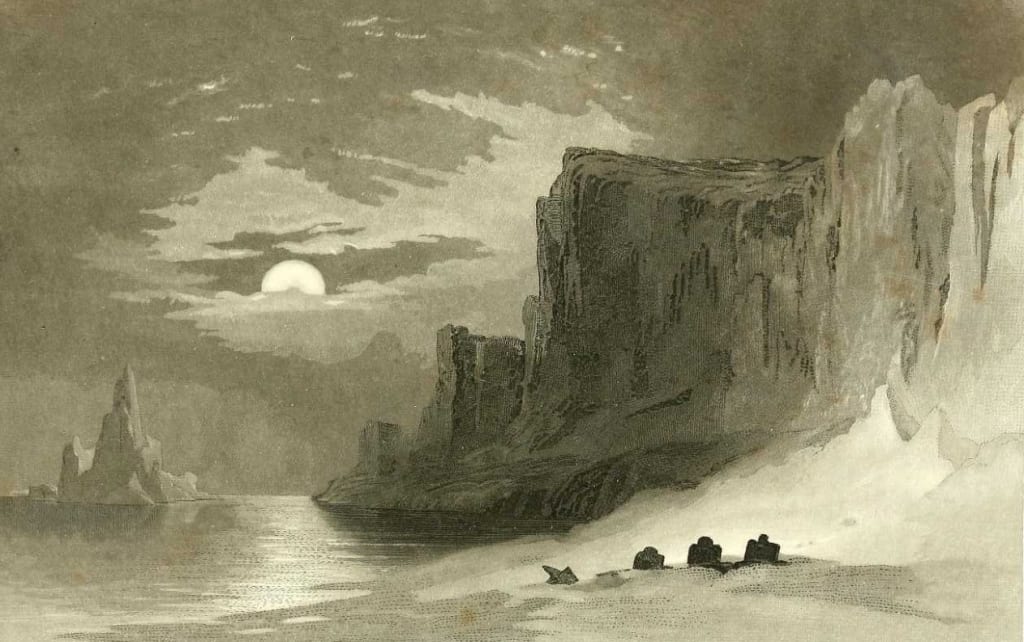

John Torrington was the first fatality of the Franklin Expedition. Led by Sir John Franklin, the expedition had set out to find the last link of the Northwest Passage through the Arctic. Most of the passage had already been discovered, and the expedition was supplied with plenty of food, steam engines, and reinforced ships. Everyone assumed they would be home in a year or two, the passage finally conquered.

No one survived.

Exactly what happened to the Franklin Expedition is still not fully understood. But Torrington has the dubious honor of having died first and being buried on Beechey Island, a small strip of land in the Arctic. The expedition had sheltered on Beechey during their first winter, and three men died and were buried there. Torrington died on January 1, 1846, at just twenty years old. John Hartnell died a few days later, on January 4, and William Braine followed a few months afterward on April 3.

When the expedition failed to return home after a few years, rescue missions tried to find them. They discovered the expedition’s winter quarters—and the graves.

The wooden headboards of Torrington, Hartnell, and Braine, painted an ominous black, were not a good sign for the rescue crews. Previous expeditions to the Arctic had lost crewmembers—Franklin’s first Arctic expedition lost more than half its men—but losing three men in the first winter was unusual. As the years went by and the rest of Franklin’s crew were still missing, it became apparent there were no survivors. Skeletons, scattered relics, and a brief message placed in a cairn of stones would show that the ships had become stuck in the ice for two years and the men had tried to walk across the barren land to safety. Before their trek, however, they had lost a significant number of men already, including Franklin himself.

The question of how the expedition met its doom has plagued rescue missions, scholars, and armchair enthusiasts for nearly two centuries. One man, anthropologist Owen Beattie, thought the answer could be found with the men buried on Beechey.

In the early 1980s, Beattie had found bones from members of the Franklin Expedition on King William Island, where most of the crew is believed to have met their demise. These bones contained high levels of lead. Beattie theorized that lead poisoning, caused by the lead-soldered cans of food brought along as provisions, may have contributed to the expedition’s downfall, but to prove it he would need to find soft tissue samples. In 1984, he led a team to Beechey Island. He hoped the permafrost had preserved the three men buried there so he could extract tissue to prove his theory. He started with the first man to die, John Torrington.

When Torrington was exhumed, Beattie discovered the permafrost had not only preserved the body, it had preserved it so well that Torrington appeared as if he had only just died. His blue eyes were half open, staring back at the scientists. Although his lips had curled up due to the desiccation process that had mummified him and a navy blue cloth covering his face had stained his forehead, he could have otherwise been mistaken for someone sleeping.

Torrington’s autopsy showed he had been very sick. His lungs were blackened—a combination of living in the heavily polluted city of Manchester, working as a stoker (someone who tends to coal-powered steam engines), and smoking. He had signs of previous lung infections and possibly emphysema, and he most likely had tuberculosis. The actual cause of death could not be determined, but it was suggested that pneumonia, brought about by the tuberculosis, was the culprit. Torrington did have high levels of lead in his hair and bones, which Beattie used as proof of his theory, but many subsequent studies have poked holes in his research. For one thing, lead levels were high for many people living in England during the Victorian period, and Torrington would have come into contact with a significant amount of lead prior to the expedition by working as a stoker (coal ash contains lead) and living in an industrial city like Manchester, where factories constantly spewed coal dust into the air.

The lead in Torrington’s system wouldn’t have helped his health, but it wasn’t what caused him to die. The other two men buried on Beechey showed signs of tuberculosis as well, which probably led to all three of their deaths. Tuberculosis is highly contagious, and it may have spread among the rest of the crew, but it is uncertain if this is what caused the high number of deaths early on or if other factors—accidents, tainted food, other ailments—were to blame. The missing ships, Erebus and Terror, have since been found in recent years, but why the entire crew died is still unknown and may never be solved.

But while people focus on the mystery and gawk over the photos of Torrington’s mummified body, it is often forgotten that the man staring back from those pictures was a human being. He was young, barely an adult. He had a family back home waiting for him. We know very little about him—the bare bones of his life have been pieced together through a small handful of records and the headboard of his grave—but we know that he lived. He had a life and maybe dreams of something better than the lot of a lowly stoker. And we know that today he was baptized, his parents taking him to church for the sacrament all those years ago. He was loved, he was cared for. And for that, too, he should be remembered.

Comments

Lauren Triola is not accepting comments at the moment

Want to show your support? Become a pledged subscriber or send them a one-off tip.