The Man Behind the Peanut

Who was George Washington Carver?

Peanuts. That’s what most people think of when they think about George Washington Carver, the famed African American scientist and inventor. And while peanuts did play a big part in his life, there’s so much more to Carver’s story than just his work with everyone’s favourite ballpark snack…

YOUNG GEORGE

As with many other Black children born into slavery, the date of Carver’s birth is unknown, though it’s thought to be sometime in 1864, just before the end of the Civil War and abolition. He was born near Diamond Grove (now Diamond), Missouri, on a plantation owned by a white farmer named Moses Carver. About a decade earlier, Moses had bought Carver’s mother, Mary, when she was just 13 years old.

Just a week after his birth, Carver was kidnapped from Moses’ farm along with his mother and sister by slave raiders from the neighbouring state of Arkansas (one of many bands of slave raiders that roamed the South during the Civil War). The three were sold in Kentucky. Moses hired a Union scout to retrieve them, but the man could only track down George. He purchased him in exchange for one of Moses’ horses.

Moses and his wife Susan raised Carver as their own, alongside their son, James. As no local schools accepted Black students at the time, Susan took it upon herself to teach Carver how to read and write. While his surrogate-brother James worked the fields with Moses, Carver was too frail and sickly as a child for such manual labour. So instead Susan taught him what one might learn in a home economics class—cooking, mending, embroidering, and (importantly) gardening.

It was through this gardening that Carver developed an interest in plants and began experimenting with pesticides, fungicides, and soil conditioners. He even became known as “the plant doctor” to farmers around Diamond due to his ability to figure out how to improve the health of their crops.

EARLY EDUCATION

At the age of 11, Carver left Moses’ farm for the nearby town of Neosho, Missouri, so he could attend an all-Black school there. He was taken in by Andrew and Mariah Watkins, an African American couple. When he first identified himself as “Carver’s George” to Mariah (as he had done his entire life), she told him that, from then on, he would be know as “George Carver” and the name stuck.

A mid-wife and nurse, Mariah imparted upon Carver her knowledge of medicinal herbs. She was also a deeply religious woman and instilled in him the importance of faith. Mariah made an indelible impression upon Carver, especially with words like: “You must learn all you can, then go back out into the world and give your learning back to the people.”

Carver was quite unhappy with the education he received at the school in Neosho, so he moved to Fort Scott, Kansas, to attend an academy there, joining many fellow African Americans traveling west at that time. After witnessing the killing of a Black man by a group of Whites, however, Carver left the city.

For the next decade or so, he bounced around from one Midwestern town to another, surviving off the skills and knowledge he had picked up from his foster mothers. In 1880, he graduated from Minneapolis High School in Kansas and then applied to Highland College, an all-White school.

Though he was initially accepted at Highland, when Carver arrived there and the administration learned he was Black, they refused him. For the next few years, he scraped by in Kansas, doing odd jobs around town for money, before moving on to Winterset, Iowa. There he befriended Helen and John Milholland, a White couple. Helen in particular took a liking to Carver and advised him to attend college.

Despite his earlier hiccup at Highland, in 1890, Carver enrolled at Simpson College, a Methodist school that let in all qualified applicants regardless of race. At Simpson, Carver studied art and piano, with the intent of one day earning a teaching degree.

During this time, Carver developed his painting and drawing skills, often sketching flowers and other botanical samples. One of his professors at Simpson, Etta Budd, recognized Carver’s aptitude for drawing (particularly the natural world). When she learned of his interests in plants and flowers, Budd encouraged Carver to apply to the Iowa State Agricultural School (now Iowa State University) to study botany, worried that a Black man in that day and age would struggle to make a living as an artist.

HIGHER LEARNING

The following year, in 1891, Carver moved to Ames, Iowa, where he began studying botany as the first Black student at Iowa State. Carver excelled in his studies, and by 1894, he had become the first African American to earn a Bachelor of Science degree.

Carver’s professors were so impressed with his research (on the subject of fungal infections of soybean plants) that they asked him if he would stay for graduate studies. He worked with renowned botanist L.H. Pammel at the Iowa State Experimental Station, learning to identify and treat plant diseases, establishing a reputation for himself as a botanist with a bright future. In 1896, Carver earned his Master of Agriculture degree and went on to teach as the first Black faculty member at Iowa State.

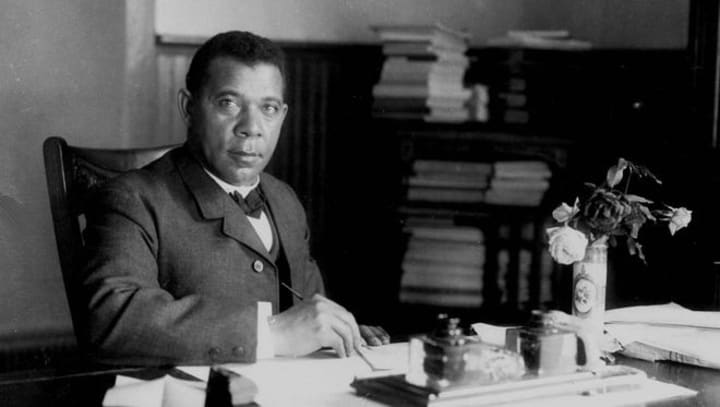

After earning his degree, Carver received offers from several schools to teach and perform research. The most attractive came from Booker T. Washington (whose last name Carver would later adopt). Washington was the founder of the historically Black Tuskegee Institute in Alabama and talked the university’s trustees into establishing an agricultural school. Carver accepted Washington’s offer and would work at Tuskegee for the remainder of his life, earning its agricultural school national renown and shaping its curriculum and faculty.

Carver’s time spent at Tuskegee was not without its difficulties. For one, agriculture training was not popular. In the South, farmers thought they knew all there was to know about farming, and students viewed going to school as a way to escape the fields. Many faculty also resented Carver for his high salary and demand to have two dormitory rooms—one for him and one for plant specimens. Additionally, he faced animosity because he had earned his master’s degree not only in a scientific field but from a “White” institution.

Carver also struggled with the demands of his duties. He wished to devote all his time to researching agriculture, with the aim of helping out poor farmers in the South, but he was expected to manage the school’s farms, teach, ensure the sanitary facilities worked properly, and sit on multiple committees and councils. Carver submitted or threatened his resignation on several occasions during his tenure at Tuskegee. Each time, however, Washington smoothed things over.

Carver and Washington had a complicated relationship to say the least and would often butt heads. Their disputes generally revolved around Carver not wanting to teach (though he was well-liked by his students). In 1915, when Washington died, Carver at last got his way. Washington’s successor relieved Carver of all teaching duties (except for summer school).

RESEARCH AND INVENTIONS

By the time Washington died, Carver had already achieved great success in the laboratory and had also made a significant impact on his community. He invented the Jessup wagon, a sort of mobile horse-drawn classroom (which doubled as a laboratory) that allowed Carver to teach farmers how to grow crops. His championing of crop rotation techniques proved most beneficial for farmers.

Through his research, Carver had learned that years of growing cotton depletes nutrients from soil, resulting in low yields. But by growing crops that return nitrogen to the earth such as peanuts, soybeans, and sweet potatoes, soil can be restored. And when the land is reverted back to cotton use after a few years, the yields increase significantly. Carver’s work in popularizing alternative cash crops immensely helped farmers in areas heavily planted with cotton, especially during the early 1900s when a boll weevil (beetle) infestation swept Alabama.

Though farmers enjoyed the high yields of cotton they were getting from crop rotation, the technique also produced surpluses of peanuts and other crops, for which there was little demand. So Carver shifted his research towards finding alternative uses for these products. He came up with numerous for sweet potatoes, including edible products like flour and vinegar, and non-food items such as stains, dyes, paints, and ink.

But by far Carver’s biggest success came from peanuts (though contrary to popular belief, he did not invent peanut butter). He developed upwards of 300 products from the legume, including milk, sauce, oil, paper, cosmetics, and soaps. Carver also did research into the medicinal uses of the peanut, though many of his discoveries never found widespread popularity.

In 1920, Carver delivered a speech before the Peanut Growers Association, advocating for the vast potential of the legume. In 1921, he appeared before the Ways and Means Committee of the US House of Representatives to ask for tariffs protection on peanuts as US peanut farmers were being undercut by Chinese importers. Carver talked about the wide range of products that could be produced from peanuts, convincing the committee to approve the tariff and earning himself the moniker “The Peanut Man”.

FAME

During the latter chapter of his days, Carver lived as somewhat of a minor celebrity. Three US presidents—Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge, and Franklin Roosevelt—met with him (Theodore in particular greatly admired Carver’s work, so much so that he sought his advice on agricultural matters in the country). Carver was invited by Henry Ford to speak at a chemurgy conference and they developed a friendship. Time magazine even dubbed him the “Black Leonardo.”

Carver was also recognized abroad. In 1916, he was made a member of the British Royal Society of Arts, a truly rare honour for an American. He also traveled to India to meet with Mahatma Gandhi and talk about nutrition in developing nations.

Carver never basked in the limelight that came with his celebrity. His focus was always on using his notability to help people and to promote scientific causes which he felt important. He wrote a syndicated newspaper column, Professor Carver's Advice. He toured the US, talking about the importance of agricultural innovation. And he also traveled the South to promote racial harmony, visiting many White Southern colleges as part of the Commission on Interracial Cooperation.

Until the year of his death, Carver also released bulletins for the public. While some of these reported on his research findings, many were more practical and included information for farmers, science for teachers, and recipes for housewives. His most popular bulletin was How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption.

Carver lived a rather frugal life, and near the end of his days, he used his savings to establish the George Washington Carver Museum in Tuskegee. Still around to this very day, the museum is devoted to his research and includes some of his paintings and drawings. In addition to the museum, Carver established the George Washington Carver Foundation, aimed at supporting agricultural research of the future.

FAITH

Carver became a Christian when he was still a young boy after an encounter with a White neighbour of his. He believed not only that he could have faith in both religion and science, but that his faith in the former was necessary to most effectively perform the latter. Throughout his career, Carver always found friendship with fellow Christians and leaned on them when criticized by the scientific community and the media. Though it definitely influenced his research, Carver viewed faith as a means of breaking down the barriers of racism and social inequality.

When it came to his students, he was just as (if not more) concerned with their character development as he was with their intellectual progression. He put together a list of eight virtues for his students to strive toward:

1. Be clean both inside and out

2. Neither look up to the rich nor down on the poor

3. Lose, if need be, without squealing

4. Win without bragging

5. Always be considerate of women, children, and older people

6. Be too brave to lie

7. Be too generous to cheat

8. Take your share of the world and let others take theirs

At the request of some of his students, in 1906, Carver began to lead a Bible class on Sundays at Tuskegee, and was known for portraying stories from scripture by acting them out. He responded to critics of his unorthodox method with: “When you do the common things in life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world.”

RELATIONSHIPS

Though he had many friendships throughout his life, Carver never married. At age 40, he started a courtship with Sarah L. Hunt—an elementary school teacher and also the sister-in-law of the Treasurer of Tuskegee Institute. It only lasted three years. Some believe Carver might have been bisexual and merely went along with the social norms of the times he lived during.

In his seventies, Carver developed a friendship and a research partnership with a young Black scientist named Austin W. Curtis, who came to teach at Tuskegee. As Carver’s health declined, Curtis Jr. assisted him around the laboratory with his research and accompanied him when he had to travel. Before he died, Carver bequeathed to Curtis the royalties from a biography that he authorized just prior to his passing.

DEATH AND LEGACY

Carver passed away on January 5, 1943, at the age of 78, after a fall down the stairs of his home at Tuskegee. He was buried on the school grounds, right next to Booker T. Washington.

Shortly after Carver’s death, then President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed off on legislation for him to receive a national monument (until then, only renowned presidents George Washington and Abraham Lincoln had had that honour). The George Washington Carver National Monument was the first ever monument dedicated to an African American, and still stands in Carver’s birthplace of Diamond, Missouri.

Carver’s list of accolades is endless. In 1977, he was elected into the Hall of Fame for Great Americans. In 1990, he was inducted into the ranks of the National Inventors Hall of Fame. In 1994, Iowa State University awarded him with a Doctor of Humane Letters. And that’s not even scratching the surface…

Carver appeared on US commemorative postal stamps in 1948 and 1998, and also a commemorative half-dollar coin minted between 1951 and 1954. Many US schools bear his name, as do a pair of US military ships. In 2005, the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis opened the George Washington Carver Garden and erected a life-size statue of the garden's namesake.

So, who exactly was the man behind the peanut? The epitaph upon Carver’s grave sums him up best:

A life that stood out as a gospel of self-forgetting service. He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honour in being helpful to the world. The center of his world was the South, where he was born in slavery…and where he did his work as a creative scientist.

About the Creator

Reuben Blaff

Astrophysics graduate student at York University | Editor and co-founder at spkesy.ca

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.