The Life, Trial, and Death of Gilles de Rais

An investigative biography of the Commander in the French armed forces, The Infamous serial killer that shook the Middle Ages to its knees, and a soldier in-arms of Joan of Arc.

Gilles de Rais (date of birth obscure, not sooner than 1405 – 26 October 1440), Baron de Rais (French: [də ʁɛ]), was a knight and master from Brittany, Anjou, and Poitou, an innovator in the French armed forces, and a buddy in arms of Joan of Arc. He is most popular for his standing and later conviction as an admitted chronic enemy of youngsters.

An individual from the House of Montmorency-Laval, Gilles de Rais grew up under the tutelage of his maternal granddad and expanded his fortune by marriage. He procured the blessing of the Duke of Brittany and was conceded to the French court. From 1427 to 1435, Rais filled in as an officer in the French armed force and battled close by Joan of Arc against the English and their Burgundian partners during the Hundred Years' War, for which he was named Marshal of France.

In 1434 or 1435 he resigned from military life, drained his abundance by organizing a lavish dramatic display of his structure, and was blamed for fiddling with the mysterious. After 1432, Rais was blamed for taking part in a progression of youngster murders, with casualties potentially numbering in the hundreds. The killings concluded in 1440 when a fierce debate with a minister prompted a clerical examination that exposed the wrongdoings and ascribed them to Rais. At his preliminary, the guardians of missing kids in the encompassing region and Rais' confederates in wrongdoing affirmed against him. He was sentenced to death and hanged at Nantes on 26 October 1440.

Rais is accepted to be the motivation for the French folktale "Bluebeard" ("Barbe Bleue"), which is most punctual recorded in 1697.

Early life

Gilles de Rais was brought into the world on an obscure date, maybe in late 1405 to Guy II de Montmorency-Laval and Marie de Craon in the family palace at Champtocé-Sur-Loire. Following the passing of his dad and mom in 1415, Gilles and his more youthful sibling René de La Suze were put under the tutelage of Jean de Craon, their maternal granddad. Craon was a rascal who endeavored to mastermind the marriage of 12-year-old Gilles to four-year-old Jeanne Paynel, probably the most extravagant beneficiary in Normandy; when the arrangement fizzled, he endeavored ineffectively to join the kid with Béatrice de Rohan, the niece to the Duke of Brittany. On 30 November 1420, Craon significantly expanded his grandson's fortune by wedding him to Catherine de Thouars of Brittany, a beneficiary of La Vendée and Poitou. Their lone youngster, Marie, was brought into the world in 1433 or 1434.

Military career

Soon after the Breton War of Succession (1341–64), the crushed group drove by Olivier de Blois, Count of Penthièvre, kept on plotting against the Dukes of the House of Montfort. The Blois group, which would not surrender its case to administer over the Duchy of Brittany, had taken Duke John VI prisoner disregarding the Treaty of Guérande (1365). Jean de Craon took the side of the House of Montfort. After the Duke's delivery, Jean de Craon and his grandson Gilles de Rais were remunerated for their "great and striking administrations" with liberal land gives that were changed over to financial gifts.

In 1425, Rais showed up in the company of lord Charles VII at Saumur yet he was possibly acquainted with the illustrious court before this date. At the fight for the Château du Lude, he killed or took prisoner the English skipper Blackburn.

From 1427 to 1435, Rais filled in as an officer in the Royal Army, separating himself for dauntlessness in the combat zone during the recharging of the Hundred Years' War. In 1429, he battled close by Joan of Arc in a portion of the missions pursued against the English and their Burgundian partners. He was available with Joan when the English Siege of Orléans was lifted.

On 17 July 1429, Rais was one of four masters picked for the honor of bringing the Holy Ampulla from the Abbey of Saint-Remy to Notre-Dame de Reims for the sanctification of Charles VII as King of France. Around the same time, he was formally made a Marshal of France.

Following the Siege of Orléans, Rais was allowed the option to add a boundary of the imperial arms, the fleur-de-lys on a purplish-blue ground, to his own. The letters patent approving the presentation referred to his "high and praiseworthy administrations", the "extraordinary risks and risks" he had defied, and "numerous other fearless accomplishments". In May 1431, Joan of Arc was scorched at the stake in Rouen.

Jean de Craon, Rais' granddad, passed on November 1432, and, in a public motion to stamp his disappointment with Rais' foolish expenditure of a painstakingly amassed fortune, passed on his sword and his breastplate to Rais' more youthful sibling René de La Suze.

Private life

In either 1434 or 1435, Rais steadily pulled out from military and public life to seek after his advantages: the development of an amazing Chapel of the Holy Innocents (where he directed in robes of his plan), and the creation of a dramatic display, Le Mystère du Siège d'Orléans. The play comprised more than 20,000 lines of the refrain, requiring 140 talking parts and 500 additional items. Rais was practically bankrupt at the hour of the creation and started selling property as right on time as 1432 to help his luxurious way of life. By March 1433, he had sold every one of his homes in Poitou (aside from his significant other's) and all his property in Maine. Just two palaces in Anjou, Champtocé-Sur-Loire and Ingrandes, stayed in his ownership. A large portion of the complete deals and home loans was spent on the creation of his play. It was first acted in Orléans on 8 May 1435. 600 ensembles were built, worn once, disposed of, and developed once more for resulting exhibitions. Limitless supplies of food and drink were made accessible to onlookers to Rais' detriment.

In June 1435, relatives assembled to put control on Rais. They engaged Pope Eugene IV to deny the Chapel of the Holy Innocents (he rejected) and conveyed their interests to the lord. On 2 July 1435, a regal declaration was announced in Orléans, Tours, waves of anger, Pouzauges, and Champtocé-Sur-Loire reproving Rais as a squanderer and disallowing him to sell any more property. No subject of Charles VII was permitted to go into any agreement with him, and those in charge of his palaces were prohibited to discard them. Rais' credit fell quickly and his loan bosses squeezed upon him. He acquired vigorously, utilizing his objets d'art, compositions, books, and attire as security. At the point when he left Orléans in late August or early September 1435, the town was covered with valuable articles he had to abandon. The order didn't have any significant bearing on Brittany, and the family couldn't convince the Duchy of Brittany to implement it.

Occult involvement

In 1438, as per the declaration at his preliminary by the minister Eustache Blanchet and the priest François Prelati, Rais conveyed Blanchet to look for people who knew speculative chemistry and evil presence bringing. Blanchet reached Prelati in Florence and convinced him to take administration with his Master. Having assessed the mysterious books of Prelati and a voyaging Breton, Rais decided to start exploring, the first in the lower corridor of his palace at Tiffauges, endeavoring to bring an evil spirit named Barron. Rais furnished an agreement with the evil presence for wealth that Prelati was to provide for the devil later.

As no devil showed after three attempts, the Marshal became disappointed with the absence of results. Prelati said Barron was irate and required the contribution of parts of a youngster. Rais gave these remainders in a glass vessel at a future inspiration, however without any result, and the mysterious tests left him unpleasant and his abundance seriously drained.

Child murders

In his admission, Rais said he submitted his first attacks on youngsters between spring 1432 and spring 1433. The primary killings happened at Champtocé-Sur-Loire, however, no record of them endure. Soon after, Rais moved to Machecoul, where, as per his admission, he killed, or requested to be killed, an enormous yet unsure number of kids after he sodomized them.

The originally recorded instance of youngster grabbing and murder concerns a kid of 12 called Jeudon (first name obscure), a disciple to the furrier Guillaume Hilairet. Rais' cousins Gilles de Sillé and Roger de Briqueville requested that the furrier loan them the kid to take a message to Machecoul, and, when Jeudon didn't return, the two aristocrats told the inquisitive furrier that they were uninformed about the kid's whereabouts and proposed he had been stolen away by hoodlums at Tiffauges to be made into a page. At Rais' preliminary, the occasions were authenticated by Hilairet and his better half, the kid's dad Jean Jeudon, and five others from Machecoul.

In his 1971 history of Rais, Jean Benedetti lets how the youngsters know who fell into Rais' hands were killed:

The kid was spoiled and wearing preferable garments over he had known at any point ever. The evening started with an enormous feast and substantial drinking, especially hippocras, which went about as an energizer. The kid was then taken to a second-story space to which just Gilles and his quick circle were conceded. There he was faced with the real essence of his circumstance. The shock in this way created on the kid was an underlying wellspring of joy for Gilles.

Rais' guardian Étienne Corrillaut, known as Poitou, was an assistant in large numbers of the violations and affirmed that his lord stripped the kid exposed and draped him with ropes from a snare to keep him from shouting out, then, at that point, jerked off upon the youngster's paunch or thighs. On the off chance that the casualty was a kid, he would contact his privates (especially gonads) and bottom. Bringing the casualty down, Rais ameliorated the youngster and guaranteed him he simply needed to play with him. Rais then, at that point, either killed the kid himself or had the youngster killed by his cousin Gilles de Sillé, Poitou, or another protector called Henriet. The casualties were killed by beheading, slitting of their jugulars, dissection, or breaking of their necks with a stick. A short, thick, blade that cuts both ways called a braquemard was kept within reach for the homicides. Poitou further affirmed that Rais here and there mishandled the people in question (regardless of whether young men or young ladies) before injuring them and at different occasions after the casualty had been cut in the throat or executed. As indicated by Poitou, Rais despised the casualties' sexual organs, and took "limitlessly more delight in debasing himself as such … than in utilizing their regular hole, ordinarily."

In his admission, Gilles affirmed that "when the said youngsters were dead, he kissed them and the individuals who had the most attractive appendages and heads he held up to appreciate them, and had their bodies cold-bloodedly cut open and took enchant at seeing their internal organs; and frequently when the kids were biting the dust he sat on their stomachs and enjoyed seeing them kick the bucket and chuckled".

Poitou affirmed that he and Henriet consumed the bodies in the chimney in Rais' room. The garments of the casualty were set into the fire piece by piece so they consumed gradually and the smell was limited. The cinders were then tossed into the cesspit, the canal, or other concealing spots. The last recorded homicide was of the child of Éonnet de Villeblanche and his significant other Macée. Poitou paid 20 sous to have a page's doublet made for the person in question, who was then attacked, killed, and burned in August 1440.

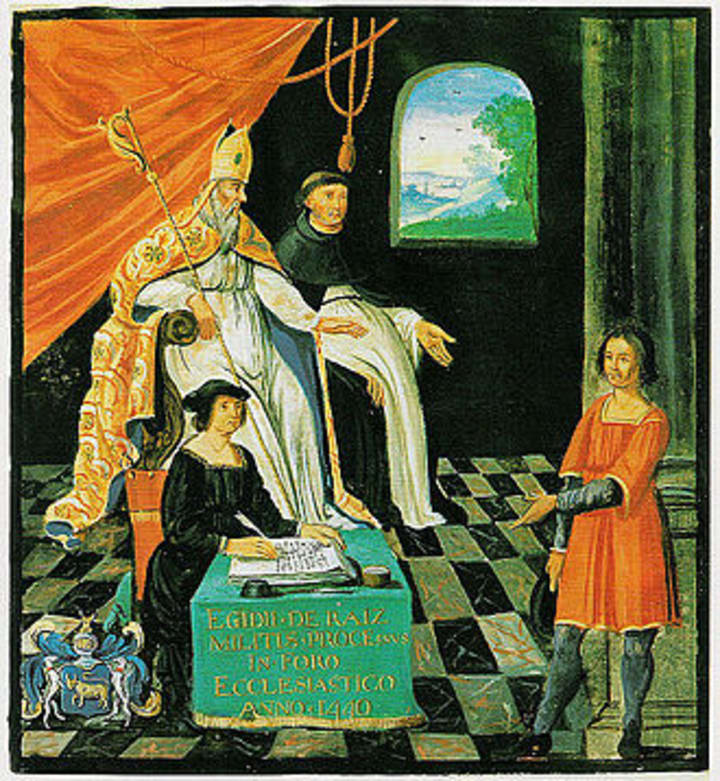

Trial and Execution

On 15 May 1440, Rais captured a pastor during a question at the Church of Saint-Étienne-de-Mer-Morte. The demonstration provoked an examination by the Bishop of Nantes, during which proof of Rais' violations was revealed. On 29 July, the Bishop delivered his discoveries, and he in this manner got the prosecutorial collaboration of Rais' previous defender, John VI, Duke of Brittany. Rais and his protectors Poitou and Henriet were captured on 15 September 1440, following a common examination that authenticated the Bishops. Rais' arraignment was similarly led by both common and clerical courts, on charges that included homicide, homosexuality, and blasphemy.

The broad observer declaration persuaded the appointed authorities that there were sufficient grounds to build up the responsibility of the blamed. After Rais conceded to the charges on 21 October, the court dropped an arrangement to torment him into admitting. Workers of adjoining towns had before started to make allegations that their youngsters had entered Rais' palace asking for food and were gone forever. The record, which included a declaration by the guardians of large numbers of these kids just as realistic portrayals of the homicides given by Rais' assistants, was supposed to be excessively startling to the point that the appointed authorities requested the most exceedingly terrible parts to be completely disregarded.

The quantity of Rais' casualties isn't known, as the vast majority of the bodies were scorched or covered. The quantity of murders is by and large positioned somewhere in the range of 100 and 200; a couple has guessed that there were more than 600. The casualties went in age from 6 to 18 and were transcendently young men.

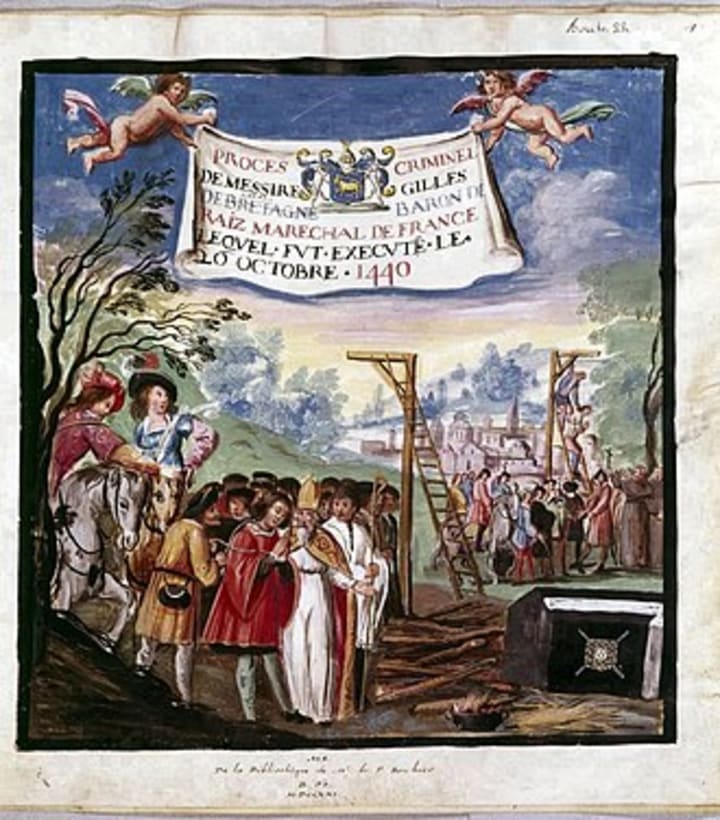

On 23 October 1440, the common court heard the admissions of Poitou and Henriet and sentenced them both to death, trailed by Rais' capital punishment on 25 October. Rais was permitted to make an admission, and his solicitation to be covered in the congregation of the religious community of Notre-Dame des Carmes in Nantes was allowed.

Execution by hanging and consuming was set for Wednesday 26 October. At nine o'clock, Rais and his two assistants continued to the spot of execution on the Ile de Biesse. Rais is said to have tended to the group with remorseful devotion and urged Henriet and Poitou to pass on boldly and consider just salvation. His solicitation to be quick to bite the dust had been allowed the other day. At eleven o'clock, the brush at the stage was set aflame and Rais was hanged. His body was chopped down before being devoured by the flares and asserted by "four women of high position" for internment. Henriet and Poitou were executed in comparative style yet their bodies were burnt up in the blazes and afterward dispersed. After much contention, the family changed the spelling variety to De Rée. This was subsequently changed over hundreds of years from De Rée to Durée after a further run-in with the Catholic Church prompting the family to become Huguenots and leave France.

Question of responsibility

Even though Gilles de Rais was sentenced for killing numerous youngsters by his admissions and the definite observer records of his confederates and casualties' folks, questions have persevered about the decision. Counterarguments depend on the hypothesis that Rais was himself a casualty of a minister plot or demonstration of retribution by the Catholic Church or French State. Questions about Rais' culpability have since a long time ago endured because the Duke of Brittany, who was given the power to indict, got every one of the titles to Rais' previous terrains after his conviction. The Duke then, at that point, split the land between his aristocrats. Essayists, for example, secret social orders expert Jean-Pierre Bayard, in his book Plaidoyer pour Gilles de Rais, fight he was a survivor of the Inquisition.

In 1992, Rais was retried during a media occasion in his nation of origin of France, with no authority inclusion of the public specialists and the legal body. The legal counselor Jean-Yves Goëau-Brissonnière made a long supplication at the UNESCO amphitheater in May 1992. Then, at that point, in November 1992, he coordinated again a self-announced "court" at the Luxembourg Palace to rethink the source material and proof accessible at the archaic preliminary. A group comprising of attorneys, essayists, previous French clergymen, parliament individuals, a scientist, and a clinical specialist drove by the author Gilbert Prouteau and directed by Judge Henri Juramy saw Gilles de Rais not as liable. None of them looked for proficient guidance from qualified medievalists.

The consultation, which finished up Rais was not at legitimate fault for the violations, was to some extent transformed into a fictionalized history called Gilles de Rais ou la Gueule du loup (Gilles de Rais; or, the Mouth of the Wolf), described by the essayist Gilbert Prouteau. "The case for Gilles de Rais' guiltlessness is exceptionally solid", Prouteau said. "No youngster's carcass was at any point found whatsoever palace at Tiffauges and he seems to have admitted to getting away from suspension … The allegations give off an impression of being fraudulent allegations made up by incredible opponent rulers to profit from the seizure of his territories." The writer Gilbert Philippe of the paper Ouest-France said that Prouteau was being "playful and provocative". He likewise guaranteed that Prouteau thought the retrial was fundamental "an outright joke".

Alternative historical interpretations of Gilles de Rais

In the mid-twentieth century, anthropologist Margaret Murray and medium Aleister Crowley scrutinized the contribution of the minister and mainstream experts for the situation. Crowley portrayed Rais as "in pretty much every respect...the male likeness Joan of Arc", whose fundamental wrongdoing was "the quest for information". Murray, who spread the witch-religion theory, conjectured in her book The Witch-Cult in Western Europe that Rais was a witch and a follower of a ripeness clique focused on the agnostic goddess Diana. Most history specialists reject Murray's hypothesis. Norman Cohn contends that it is conflicting with what is known about Rais' wrongdoings and preliminary. Students of history don't see Rais as a saint to a pre-Christian religion; different researchers will in general view him as a passed Catholic who slid into wrongdoing and degeneracy, and whose genuine violations caused the land relinquishments.

About the Creator

Deana Contaste

I enjoy writing poetry, stories, and creating art in general, but I also try to survive in the world like every other human being.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.