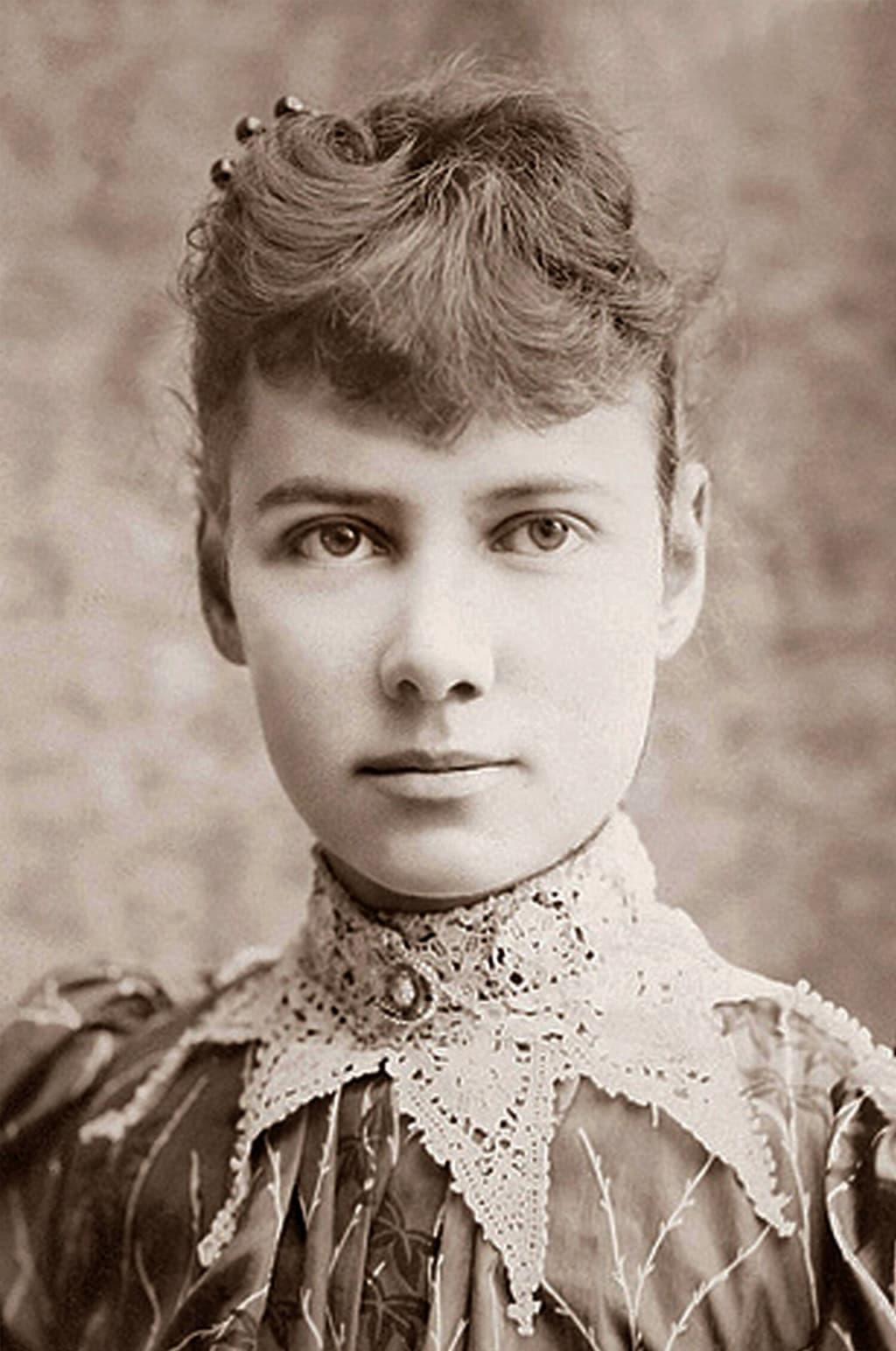

Nellie Bly | Women of History

How a Young, Female Journalist Made History

Even if you’ve never heard Nellie Bly’s name, you may already know a little bit about her story. In this case, you may have seen the show American Horror Story -- in particular, the second season Asylum. If you’ve seen it, you know that Sarah Paulsen plays a journalist named Lana Winters; she gets herself committed to an insane asylum in order to expose the horrific treatment practices and abuse taking place there. The story of Lana Winters on American Horror Story was loosely based on just one piece of the incredible life story of Nellie Bly, the subject of this edition of Women of History.

Nellie Bly is actually a pen name. She’s born Elizabeth Jane Cochran in Pennsylvania, in 1864. When she’s 21, Elizabeth reads an article in the Pittsburgh Dispatch titled “What Girls Are Good For,” which is a column claiming that a woman’s purpose is having children and keeping house, not having an education or a career. So Elizabeth writes a scathing response to this article, signs it “Little Orphan Girl,” and submits it to the newspaper. The editor of the newspaper is so impressed by it that he places an ad to track down the “Little Orphan Girl,” and offers her a full time job writing under the name Nellie Bly.

At first Nellie does investigative journalism, writing about everything from how divorce proceedings are inherently discriminatory towards women, to a series on women working in factories. But factory owners start to complain about the articles, since they don’t cast factory conditions in a particularly favorable light, and they start threatening to pull advertising from the newspaper. Which means Nellie is now assigned a new task: an article about gardening. Which, of course, is regarded as a much more appropriate assignment for a female journalist at the time. Nellie writes the article, then turns it in -- along with her resignation.

Then Nellie leaves and travels to Mexico, and continues writing. She sends back travel pieces to be published -- which would later become her book Six Months In Mexico. Over time, Nellie returns to investigative pieces; this time on the Mexican government. At one point, she writes a report and protests about the arrest and imprisonment of a local journalist. In response, the Mexican government threatens to arrest her too. So she leaves Mexico to head for New York, but continues to write about the Mexican government, accusing them of having a “tyrannical czar,” of “controlling the press,” and of “suppressing the Mexican people.” (Nellie is not one to mince words.)

Now, this is where things get interesting. At 23, Nellie gets a job writing for the newspaper New York World, where she is challenged by her editor (who may or may not have been Joseph Pulitzer himself -- reports conflict) to “come up with an outlandish stunt” to grow their readership. Nellie decides to investigate the Women's Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell's Island, which she can only observe as a patient. Her editor tells her: "We do not ask you to go there for the purpose of making sensational revelations. Write up things as you find them, good or bad; give praise or blame as you think best, and the truth all the time.” So Nellie comes up with a plan: she slowly starts acting more and more erratic. She stays up all night, stops bathing, wears dirty old clothes, goes on hostile rants, wanders the streets, and practices looking crazy in a mirror. Once she has her act perfected, she checks herself into an all-women boarding house and promptly terrorizes the other guests, scaring them so badly that within a day, they report her to the police. Days later, Nellie’s plan is realized: she is loaded onto the “filthy ferry” headed to Blackwell’s Island.

Before we continue with Nellie, a little background on the Women's Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell's Island (which today is called Roosevelt Island). Dr. John McDonald, one of the designers of the facility, has this plan to separate different types of mental illness into different wings of the building, to better rehabilitate them. The facility is intended to be for the humane rehabilitation of the mentally ill, and it’s going to be the first publicly funded mental hospital -- but as with so many things in life, it comes down to money. Due to lack of funding, two significant things happen:

(1) only two wings of the proposed building are built, leading to immediate overcrowding, and

(2) the lack of funds lead to recruitment of inmates from the nearby penitentiary as guards and attendants in the asylum.

So now you have inmates from a prison trying to handle an overcrowded facility of mentally ill people, and staff trying to handle them both. This is not to excuse any part of what happens next; it’s purely for background on how this hospital started, and what it became.

Now, this asylum has been written about before this point -- most notably, by Charles Dickens, back in 1842. He visited and wrote the following: “The different wards might have been cleaner and better ordered; I saw nothing of that salutary system which had impressed me so favourably elsewhere; and everything had a lounging, listless, madhouse air, which was very painful.” So this is not the first time someone is going to write about the asylum. But Nellie is about to become the first person to go undercover to do it.

Back to Nellie: she arrives at the facility, and in her own words:

“I became one of the city's insane wards for that length of time, experienced much, and saw and heard more of the treatment accorded to this helpless class of our population, and when I had seen and heard enough, my release was promptly secured. I left the insane ward with pleasure and regret – pleasure that I was once more able to enjoy the free breath of heaven; regret that I could not have brought with me some of the unfortunate women who lived and suffered with me, and who, I am convinced, are just as sane as I was and am now myself. But here let me say one thing: From the moment I entered the insane ward on the Island, I made no attempt to keep up the assumed role of insanity. I talked and acted just as I do in ordinary life. Yet strange to say, the more sanely I talked and acted the crazier I was thought to be.”

Nellie’s account of her experience inside the asylum talks about any number of horrors. She discusses the fact that a German couple is admitted at the same time she is; to hear her tell it, the couple is committed not because they are mentally ill, but because they speak German and can’t make themselves understood. At her first meal in the facility, Nellie doesn’t eat dinner because she tries a bite or two and deems the food inedible. Later, she and all the other patients are taken in turns to be stripped naked, scrubbed, and have freezing water poured over them. She mentions that when she’s done, she feels sorry for the woman after her, because: “Imagine plunging that sick girl into a cold bath when it made me, who have never been ill, shake.” She mentions that every patient is washed in the same water, so the transmission of illness is high.

Her first night there, she’s only given a short wool blanket, so even when she’s freezing she can’t cover her whole body. Nellie and the other patients are kept constantly freezing, even when they ask for blankets, shawls, or hats. The guards and night nurse enter her cell multiple times, waking her up every time. The next morning: “the hair of forty-five women was combed with one patient, two nurses, and six combs.” When Nellie sees the Superintendent of the facility: “I asked some of them to tell how they were suffering from the cold and insufficiency of clothing, but they replied that the nurse would beat them if they told.” On a walk outside, she sees fifty-two women attached by their belts to a long rope and slowed down by an iron cart; these, she learns, are the violent patients.

Nellie only describes her first day in vivid detail, but then goes on to say that every day there was the same: she talks about the terrible quality of the food, including finding a spider in her slice of bread, and that they are sometimes given meat that’s impossible to eat because a lot of the patients don’t have teeth. For five of the days Nellie spends in the asylum, the patients are confined entirely to their rooms. She mentions almost casually that when a patient has a visitor, they are given a clean dress to keep up appearances. Nellie mentions often that anyone who complains is told to shut up, and she personally witnesses the nurses slapping and choking patients, or locking them in a closet as punishment. She relays stories from other patients, who are tied up, beaten with broom handles, have their hair pulled out by the roots, or are held underwater for being uncooperative.

So finally, after ten days in the facility, Nellie’s newspaper the World sends an attorney and gets her released. She publishes the first installment of her expose, which would later be published as the book Ten Days In a Madhouse, a few days later, which goes the 1887 version of viral; it causes outrage all across the country and prompts a grand jury trial. They ask Nellie to go with them to visit the island, and she agrees. On the way there, though, she notices that everything seems a little bit too clean, including the ferry they take to the island, and soon discovers that the staff had an hour’s warning before the Grand Jury’s arrival. But Nellie isn’t giving up that easily. She seeks out a fellow patient: Miss Anne Neville, who she had become close with over her time in the facility. Nellie tells Anne that all she needs to do is share with the Grand Jury everything that’s happened in the last ten days. Anne trusts Nellie, and is honest: she backs up all of Nellie’s claims, including the bad food, inadequate clothing, poor hygiene, and the horrific abuse from the staff.

Thanks to Nellie’s piece, the Grand Jury makes a report which launches a formal investigation and dictates the need for improvements at the facility and grants $1 million of funding to make it happen, which would be over $27 million today. The facility undergoes massive changes in administration, practices, and oversight, all thanks to the work of Nellie Bly.

But wait…..there’s more! Because Nellie isn’t done yet.

After writing one huge news story, she comes up with an idea for another.

Nellie becomes a massive success with her exposé on Blackwell’s Island. She makes a huge impact, and is an instant journalism star. She spends two years continuing to write investigative journalism pieces, and then she has a brilliant idea.

Nellie is going Around The World In Eighty Days.

This one you’ve heard of: Jules Verne publishes a book in 1972 called Around The World In Eighty Days. It’s an adventure novel chronicling the fictional trip of Phileas Fogg, whose friends bet him 20,000 pounds he can’t circumnavigate the world in 80 days. (Spoiler alert: he does. Just barely.) So Nellie has an idea: she’s going to beat his record. She’s going to do the same trip, in fewer days.

Nellie’s editors are not excited about this idea. The idea of a woman traveling without escorts seems laughable; comments are even made that women travel with too much baggage to make the trip possible. Her editor even suggests sending a male coworker instead, because only a man could do it, and she replies, "Very well, start the man, and I'll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him." She wins the argument, of course. If we know anything about Nellie at this point, we know she’s not one to back down from a challenge. She boards the ocean liner Augusta Victoria in November of that year, and she only brings two small satchels with her. She travels around the world while her newspaper back home, the World, is running a “Nellie Bly Guessing Match,” which gets folks to place bets on how long Nellie’s journey will take. Nellie even stops in France to meet Jules Verne himself, who encourages her by saying,, "If you do it in seventy-nine days, I shall applaud with both hands."

Nellie travels around the world in seventy-two days, six hours, and eleven minutes. Her trip is a huge sensation and has a massive impact on circulation and readership of her newspaper. So she returns to her office, expecting a bonus for her work, but receives nothing. She quits her job at the World as a result.

But because she’s Nellie Bly, there’s no shortage of opportunities for her. Over the next few years, Nellie goes on lecture tours, writes a book about her travel experiences, and appears on trading cards and board games.

At 31, Nellie marries a 73-year-old-man named Robert Seamen; he’s a millionaire, and the head of Iron Clad Manufacturing Company. Nellie is a star here too, registering for two patents during this time -- one for a milk carton, the other for a stacking garbage can. But just nine years after their marriage began, Robert dies, leaving Nellie in charge of the company. By all accounts, Nellie is out of her element in running the business, and due to employee embezzlement, the company goes bankrupt.

So she’s back to journalism, the heart and soul of Nellie Bly. She spends the rest of her days continuing her investigative journalism career; covering stories from the front lines of World War I. She’s the first woman to visit the war zone between Serbia and Austria, and is even arrested when she’s mistaken for a spy. She also covers stories about women’s suffrage and continues to advocate for women until her death from pneumonia in 1922, at age 57.

So a few quick points here in the present day:

Nellie’s impact on “stunt girls,” female reporters, and investigative journalism cannot be overstated. Her “moxie,” as her editor called it, paved the way for many future generations.

The Blackwell Island facility eventually closed in 1894. The building was repurposed as a hospital, and then was finally demolished in 1955. Today all that’s left of it is the octagon-shaped tower, which was the central point of the original building.

Nellie is being given a memorial on the island, which is now Roosevelt Island, to commemorate her work; the design was revealed in January of 2020 and it is expected to be built sometime in 2021.

Thanks for joining Women of History. Want more of this content? Help me write more by leaving a tip!

Sources:

Information on Nellie Bly and Blackwell’s Island researched using: The Washington Post, NPS.gov, Psychiatry Online, LisaWallerRogers.com, PrisonPolicy.org, MentalFloss.com, Nellyblyonline.com with help from archive.org, and the digital library at UPenn.edu

Information on Nellie Bly and her world trip researched using: Smithsonian magazine, Nellyblyonline.com with help from archive.org

Information on American Horror Story provided from an article by Lynsey Eidell on Glamour.com

About the Creator

Shea Keating

Writer, journalist, poet.

Find me online:

Twitter: @Keating_Writes

Facebook: Shea Keating

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.