Murder, He Wrote

Just-so stories about animal collective nouns

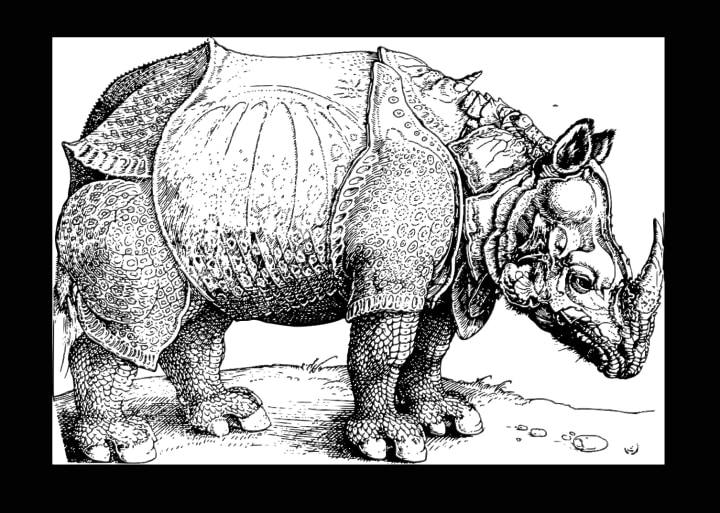

It was when someone told me about a crash of rhinos that I hit the wall.

It was one of those things that come up in casual conversation, when going down the road the of fact-finding factoids inevitably brings you to the weird and wacky anomalies of the English language, and how there’s a word for everything — even when there isn’t.

Somebody told me, in just such a conversation of collective thinking-out-loud, that the collective noun for rhinos is a crash of rhinos and my immediate reaction was: That’s bogus! That can’t be.

Oh, it be.

Mind you, it wouldn’t be the first time anyone got confused over rhino etymology.

There are two kinds of rhinos in Africa, quite aside from the ones in Asia: black rhinos and white rhinos.

Sounds simple, but wouldn’t you know, the names are themselves misleading. Rhinos are neither black nor white — they’re kind of dun color, more gray or brown than black or white. Black rhinos and white rhinos have the same color skin, you see. The only rule-of-thumb about a rhino’s external coloring is that they’re the color of the last thing they were rolling in.

This is funny because it’s true: Rhinos will roll in just about anything. And once in, they go all in.

The more accurate name for the black rhino is the hook-lipped rhino, but you won’t often hear them described that way, except in scientific circles.

That’s a shame. It would lessen the confusion if they were, because the white rhino isn’t named after its color either: ‘white’ is an anglicized bastardization of the Afrikaans word ‘wyd,’ which means ‘wide’ and — surprise! — is pronounced that way. White rhinos have a wide face and jaw, you see, while black rhinos have a more triangular jaw, a narrow face and a long, protruding lip that makes them seem as if they’re hook-lipped.

Now you know.

That can be useful information if you’re ever hiking in the African bush one day and you get nailed by a rhino. You’ll still get a horn up the rear-end, but at least you’ll know which species hit you.

Still, a crash of rhinos?

Perhaps that’ll be the answer to a Jeopardy! question one day — remember always to answer in the form of a question — but since it was already a clue on Jeopardy! once (“This is the collective noun for rhino, as in ‘a — of rhinos’”) it’s unlikely to be asked again any time soon.

And a crash of rhinos doesn’t ring true for an even better reason: They’re solitary animals by and large, and in the wild they don’t really get along. They’re not like elephants.

Oddly, the more deeply you delve into the compelling, captivating, colorful and engaging, enthralling, enchanting, exciting and entertaining world of collective nouns, you’ll soon find many of them seem to revolve around animals — creatures great and small, friendly and not-so-friendly. They may not all be social butterflies but they all have a reason to belong.

Some of these may annoy you, as a crash of rhinos did me, but who am I to quibble? These hail from the U.S. Geological Survey and Oxford Dictionaries, among other (credible) sources.

The great thing about a Covid-19 imposed lockdown, you see — to the extent that anything is great about a Covid-19 imposed lockdown — is that it gives you more time to do useful things like pore through the pages of old Oxford Dictionaries, looking for the wild and wacky and downright weird.

You'll find a swarm of bees — makes sense — and an army of caterpillars, which sounds as if it might possibly work better with ants, but there you go.

There’s a bed of clams, which sounds a little like a nest of rumors, but isn’t.

There’s a risk of lobsters, which is only a risk really if you’re trying to open a restaurant in a down economy in the middle of a pandemic.

There’s a bloom of jellyfish, though you may think of a more colorful word if you happen to swim through a group of them at night, Portuguese man o’ wars, say — or is it men o’ war? Don’t get me started.

There’s an audience of squid — stop having strange sex, please; it’s distracting, and it’s wrong — and a shiver of sharks. One is quite enough, if you ask me, especially if I’m swimming in the ocean and trying my hardest not to flail around like an injured seal.

A group of cobras is called a quiver, which makes sense because, for me, quivering doesn’t even begin to cover it.

A group of crocodiles is called a bask — crikey! — and a group of vipers is called a nest, which makes sense because anyone who’s worked in an office will be all too familiar with that.

Birds have their own word groups, some of which make sense, many of which don’t. Perhaps you can think of better ones. If you do, call the National Audubon Society. I’m sure they’d like to hear from you.

For buzzards, think a wake.

For coots, think a cover.

For cormorants, think a gulp.

For turtle doves, think a pitying.

For ducks, think a flock. (There, that one was simple now, wasn’t it — unless they’re paddling on water, in which case they’re called a raft. Now you know.)

For eagles, think a convocation.

For finches, think a charm. Works like a charm.

For flamingos, think a stand. Makes sense, when you think about it. Unless they're flying, then it doesn't.

For geese, think a gaggle (on the ground) or a skein (in flight).

For hawks, think a cast, or kettle. (Kettle works better for me.)

For jays, think a scold. I'd have saved that for magpies, but what do I know.

For magpies, think a tiding. Nope. Scold works better.

For mallards, think a brace. (Aren’t mallards ducks? There I go again.)

For nightingales, think a watch.(That’s very Game of Thrones, so it works.)

For owls, think a parliament. Which, if you ask me, is disrespectful to owls. But then I always was an anarchist at heart. V for Vendetta and all that.

For parrots, think a pandemonium. Especially if they've kept you awake all night.

For partridges, think a covey.

For penguins, think a colony or rookery.

For rooks, think a building — which is silly and confusing, because if any group of animals deserves to be called a rookery, it’s a colony of rooks.

For sparrows, think a host. Why, I have no idea.

For swans, think a bevy. Not to be confused with a belfry. That's for bats.

For teal, think a spring. Must be the color, and the greening of spring.

For turkeys, think a rafter. Gobble, gobble. (Apologies.)

And while woodcocks and woodpeckers may seem easy to confuse, they’re not really: A group of woodcocks is called a fall, while a group of woodpeckers is called a descent. See? Easy-peasy! (Not.)

As for the big, iconic species we’re all familiar with, lions assemble in prides — a great word for a great cat — and a group of leopards is called a leap. That's a bit bogus actually, because none of the bigs cats is as independent or solitary as a leopard. They can’t stand each other, in fact; males will sometimes kill females if they come across them in the wild by accident. Mating is the very definition of a one-night stand.

A group of giraffes is called a tower, which makes sense in a way, if a bit awkward at first glance.

A group of gorillas is called a band — insert your favorite here here — and a group of porcupines is called a prickle. Can you guess why? (Not likely to be a question on Jeopardy! any time soon. Either.)

A group of dolphins is called a pod or a school, which makes sense because there are those — including some scientists — who swear dolphins and whales are smarter than we are.

A group of otters is called a romp, which sounds like fun — and they are.

A group of wolves is called a pack, but then you knew that already. They’re sometimes called a rout or a route, but since pack works perfectly fine, why bother?

I’ve saved the best for last, or what I think is best, anyway. The collective noun for a group of crows is a murder, as in a murder of crows — which is probably what you feel like doing right now if you've read this far.

Please don’t. Murder, that is.

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If it tickled your fancy, feel free to tick the heart-shaped box. Tips are appreciated, too, but only if you think it warrants. Who knows, maybe one day I’ll save enough for a Happy Meal.

There are some great Facebook groups for Vocal writers like the Vocal Creators Support Group if you want to be more active in the community.

Link here: https://www.facebook.com/groups/820414142214339

Creators Support and other groups like it are great places to share and get feedback about your work, or find encouragement when you’re struggling with a piece.

Anon!

About the Creator

Hamish Alexander

Earth community. Visual storyteller. Digital nomad. Natural history + current events. Raconteur. Cultural anthropology.

I hope that somewhere in here I will talk about a creator who will intrigue + inspire you.

Twitter: @HamishAlexande6

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.