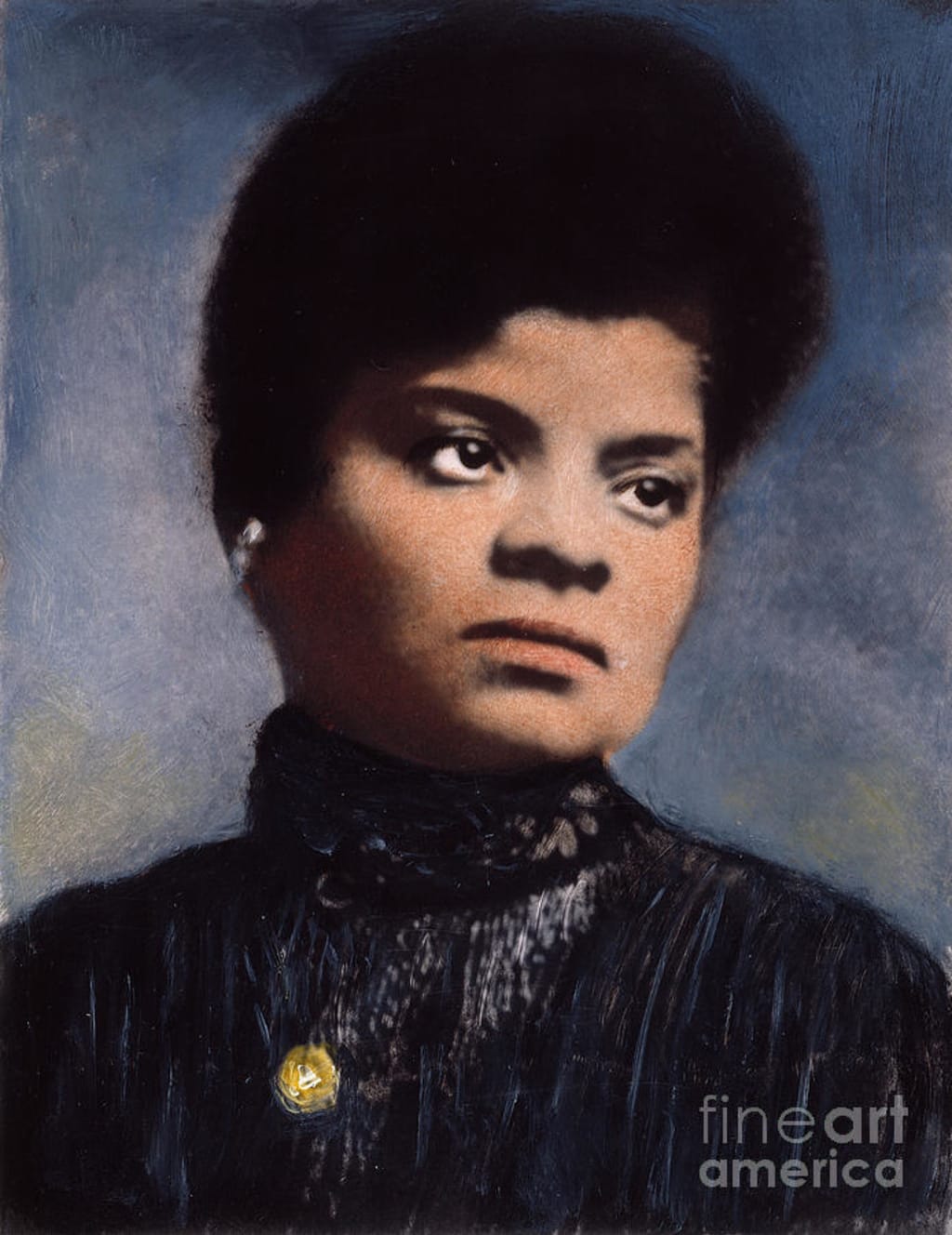

Ida B. Wells: An Underappreciated Revolutionary

An essay I wrote in 2019 about a lesser known figure of history

In 2019, transgender journalist Lewis Wallace will release a companion podcast to his upcoming book, The View from Somewhere. The podcast “features journalists from marginalized and oppressed communities who have pushed back on the ‘objective’ framework, or attempted new ways of thinking about and practicing journalism.” Among the journalists included in the podcast are Andrew Kopkind, Marlon Riggs, and the subject of this paper, Ida B. Wells. The description of a journalist who pushes back on an objective framework to spread word about an issue they think is important is appropriate for Ida, who used her power of the pen and paper to write about African-American issues in the South, particularly lynching laws surrounding African-Americans.

Ida Bell Wells (later Ida Bell Wells-Barnett) was born a slave to James and Lizzie Wells in Holly Springs, Missouri on July 16, 1862. When she was around six months old, she and her family were declared free by the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, but still faced racial prejudice as an African-American family living in Mississippi. When the war ended, James and Lizzie became politically active in the Republican party during the Reconstruction era. Because of his involvement with the Freedman's Aid Society, James served on the first board of trustees of Shaw University, a university for newly-freed slaves that he helped found. Ida attended school at Shaw (now Rust College) but had to drop out in 1878 at the age of sixteen when she found out that a yellow fever epidemic had caught up with her family. Both of her parents and one of her siblings died from the fever, leaving her the responsibility of caring for her other siblings. She got a job as a teacher during this time by convincing a nearby school administrator that she was 18. Ida was eventually able to use her parents life savings to attend Rust again, but she was expelled two years later after a dispute with the university’s president. In 1882, she moved with her family to Memphis, Tennessee, and continued her education at Fisk University in Nashville.

In 1884, Ida bought a first-class train ticket from Memphis to Nashville. This train ride would turn out to be one of, if not the most momentous occasions of her entire life. The train crew walked over to her and ordered her to move to the area of the train reserved for African-Americans. She refused to move and was forcibly removed from the train. As she was removed, she ended up biting the hand of one of the men trying to remove her. She sued the railroad company for $500 and won the case. Unfortunately, the ruling was eventually overturned by the Tennessee Supreme Court. This overturning particularly frustrated Ida, who was now inspired to write periodicals under the name “Iola” for church newspapers and African-American newspapers discussing racial and political issues in the South. She eventually secured a job in the Memphis public school system, saving her money and eventually becoming the owner of the Free Speech and Headlight newspaper in Memphis. She was fired from her teaching job in 1891 after she published an article criticizing the unequal funding of African-American schools. She continued being an outspoken voice for civil rights, with one particular case gaining her notoriety, along with probable infamy at the time.

In 1892, Tom Moss, Calvin McDowell and Will Stewart, three African-American males who were friends of Ida’s, set up a grocery store. The men had clashes with the Caucasian owner of another nearby store because the three men were drawing customers away from his store. On one particular night, the three men ended up shooting several Caucasian vandals in order to protect their store and were subsequently arrested. None of them were given a chance to defend themselves, and they were all lynched soon after. Ida decried the men’s lynchings, traveling across the South for two months to gather information about other lynchings across the country and publishing articles with the information she gathered. Angry with her editorials, a mob eventually gathered and destroyed Ida’s Memphis office. She advised her readers to abandon Memphis before leaving for New York City and continuing to write exposés for the New York Age. She lectured in Europe for a time before moving to Chicago in 1893. While there, she banded together with other African-American leaders to call a boycott of the World’s Columbian Exposition. The boycott accused the exposition committee of negatively portraying the African-American community and criticize the exposition for banning African-American performers. In response to the ban, she wrote a pamphlet called “The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition.” The same year, she published a personal examination of American lynchings that she titled A Red Record. In 1895, she married Ferdinand Lee Barnett, lawyer and editor of the Chicago Conservator, the first African-American newspaper of the city. In 1896, she formed the National Association of Colored Women (NACA). In 1906, she joined W.E.B DuBois to promote the Niagara Movement which advocated civil rights of African-Americans. In 1909, she attended a special conference for what would become the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and is credited as being one of the founders of the organization. She later cut ties with the infant organization because of its lack of action-based initiatives at the time.

Ida continued to advocate civil rights for the rest of her life. She called for President Woodrow Wilson to end discriminatory hiring practices in government jobs, created the first African-American kindergarten in her community, and continued to fight for women’s suffrage throughout the rest of her career. In 1930, Ida made a bid for the state senate which was ultimately unsuccessful. The following year, health problems cropped up, and on March 25, 1931, in Chicago, she died of kidney disease at the age of 68. Ida’s impact should not be understated; she was the first to travel abroad to seek support in the fight against lynchings, the first to risk her life to conduct investigations into lynching, the first to publish pamphlets about the economic underpinnings of lynching, and the first to put forward the idea that if voting, education, and workplace rights of African-Americans were to be protected, their senseless killings had to be stopped (Francis). With her major contributions to the rights of African-Americans and women across the country, it’s shocking that Ida didn’t even get her own street until a week before this paper was written, on February 11, 2019. The renaming of Congress Parkway to Ida B. Wells Drive makes history as the first downtown street to be named after an African-American woman. This drive now serves as a memorial to her and her legacy, as her homes in Chicago were demolished in 2002. The fact that it took so long to honor Ida with a memorial of any kind shows how underappreciated her work towards civil rights and towards really is. She made significant contributions towards the rights of African-Americans in the United States, particularly through her journaling of their lynchings, and these contributions need to be recognized.

Sources Used

"Ida B. Wells: A Courageous Voice for Civil Rights" by Patti Carr Black

“Ida B. Wells and the Economics of Racial Violence" by Megan Ming Francis

“Ida B. Wells Finally Gets a Top Honor with Street Name” by Mary Mitchell

“Ida B. Wells-Barnett” by Arlisha R. Norwood

“The View From Somewhere Podcast: Let's Get to $16K!” by Lewis Wallace

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.