I'll Go When I'm Good And Ready

The victorious army is the one that never fights

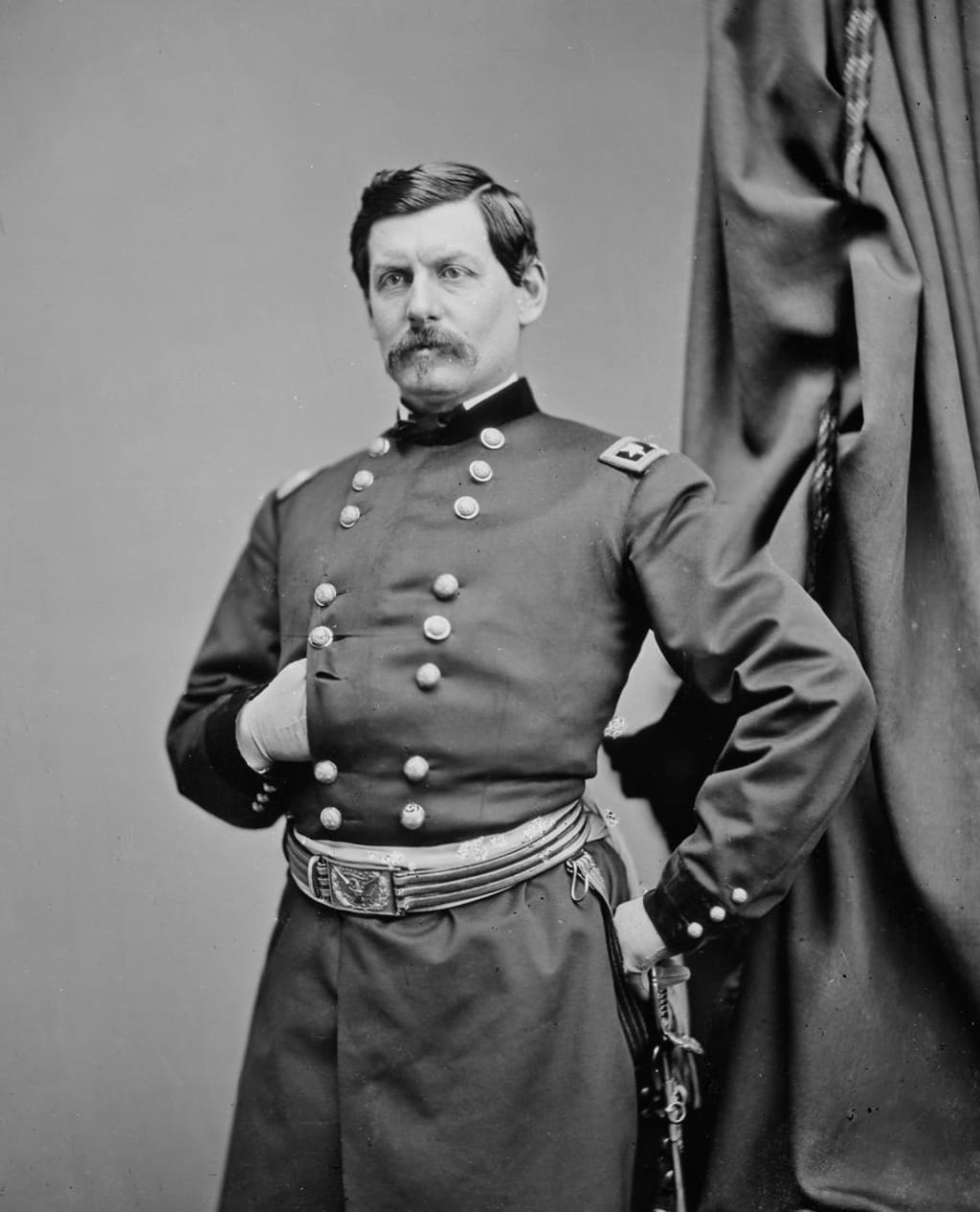

General George McClellan was outnumbered.

At age thirty-four, he was an internationally-respected military thinker and strategist (except where the cavalry was concerned; he only wanted them for guards and advance patrols. However, his invention—the McClellan saddle--was in continuous use from 1859 until the horse cavalry was disbanded in World War II. The Confederate cavalry made widespread use of it after 1863. Thanks, George).

In 1861, at the outset of the Civil War, McClellan was assigned command of the Army of the Potomac. He was the second highest ranking officer in the army. Only the aged Mexican War hero Winfield Scott was above him.

For now.

Upon arriving in Washington, McClellan did what he did best: he manufactured a crisis. He put his army to work fortifying the city against a rebel attack that he believed was imminent. A top-notch organizer and administrator, the general restored discipline to the troops in the city (in part, by forbidding them to be in the city without a pass). Fortifications were built and the army was trained and equipped for battle.

But it would never be enough.

McClellan enlisted Allan Pinkerton and his famous detective agency to spy out the enemy and report on troop strength and preparedness. While Pinkerton’s reports on other aspects of the Confederacy—the economy, politics, and morale of the rebels—were perceptive and mostly accurate, his estimates of troop strength were wildly off-base, and the commanding general believed him without question.

Much of Pinkerton’s estimates of the size of the force facing McClellan from the Virginia line came from deserters, refugees, and escaped slaves. Since these people knew Pinkerton and his agents had the power to imprison them or worse, send them back across the lines, they told the agents what they wanted to hear. And Pinkerton’s men on the ground in the Confederacy, unable to see more than individual units at a time, relied on faulty mathematical extrapolations to come up with their numbers. Rebel numbers at the end of October, 1861 were reported to McClellan at 80,000. The Confederacy’s own records at the time showed effective troop strength of only 42,000.

When these inflated numbers reached the commanding general--who, if he didn’t find an emergency was happy to manufacture one--he freaked out. It also helped that these numbers confirmed McClellan’s own assumptions. The general loved being right, and thought he was correct most of the time.

Okay--all of the time.

He believed that the holy task of saving the nation had fallen upon him alone; that he was “solely responsible for the fate of the nation” and that he “must have full and unfettered control to meet the crisis. A man of George McClellan’s inflexible certitude could not tolerate dissent from these conclusions.”

Enter his commanding officer, Winfield Scott.

Scott had a much clearer view of the situation. He knew McClellan, and he had a more reasonable expectation of the South’s capacity for war. He also surmised, as did President Lincoln and his Cabinet, that victories, or at least the appearance of forward movement by the army, was necessary to persuade the public to maintain the war effort.

McClellan, on the other hand, was going to wait until he was good and ready. And he was neither good nor ready as long as he believed he faced a force that was at least double his own. The Army of the Potomac was derisively called “McClellan’s Bodyguard” since it never moved on the enemy and only remained encamped around its general.

McClellan was a darling of the press and his men, so his conflict with old Winfield Scott went his way. The President accepted Scott’s resignation in November, 1861 and appointed McClellan general-in-chief. Lincoln suggested that the dual role of general-in-chief and commander of the Army of the Potomac was too much of a burden for one man, but McClellan assured him he was up to the task.

Which he was, as long as the army stayed where it was. The general kept sending the Cabinet inflated enemy troop numbers, always claiming he was outnumbered two to one. President Lincoln once remarked that even if he gave McClellan the 100,000 men he asked for, the next day the general would report that the enemy now had 400,000 men and he could not advance without more reinforcements.

The President’s patience with the army’s inaction was going to run out. He said in a Cabinet meeting, “If General McClellan does not want to use the Army, I would like to borrow it for a time, provided I could see how it could be made to do something.”

McClellan, always misreading the situation to suit his own opinions, believed the President was a moron and his Cabinet was hopelessly in over their heads when it came to military matters. And his response to criticism was that whoever disagreed with him was “at best ignorant and misguided and at worst a traitor.” McClellan soon “detected as many enemies at his back as he found in front of him.”

The only direction in which he went on the attack, though, was behind him. He called the President "nothing more than a well-meaning baboon", a "gorilla", and "ever unworthy of ... his high position" and often made Lincoln and the Secretary of War (who came to his headquarters instead of summoning him to the White House out of consideration for his workload) wait in his downstairs hallway for hours before seeing them. On the last of these occasions, the general made Lincoln wait for half an hour before an aide came down to tell the President that the general had gone to bed.

Lincoln ordered McClellan removed from command on November 5, 1862. A year later, the President found his general in the man McClellan once declined to meet with regarding a command in the Union Army, believing he was nothing more than a useless drunk: Ulysses S. Grant. When his subordinate generals reported to Grant that they were in position and would be able to attack in a week or two, Grant would telegraph back, “Attack the enemy tomorrow morning.”

McClellan wrote his wife, “Well, one of these days history I trust will do me justice.”

History did. McClellan lost the presidential election of 1864 (losing the military vote, which he assumed was entirely his, by a margin of 3-1), and then went to Europe for a few years. There was talk of running him for president again in 1868, but having lost out to Ulysses S. Grant in the army, he declined to oppose him. He was elected governor of New Jersey in 1878 and served one term. He published a memoir defending his wartime actions, claiming the government failed to supply him with enough men and supplies to win the war.

He died in 1885, at a time when the memoir of former President Ulysses S. Grant was a best-seller.

About the Creator

Stacey Roberts

Stacey Roberts is an author and history nerd who delights in the stories we never learned about in school. He is the author of the Trailer Trash With a Girl's Name series of books and the creator of the History's Trainwrecks podcast.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.