How a Drunk Driver Led to the Birth of Russia's Sputnik 1

In the milieu of the Cold War, a roadside accident three generations ago led to Sputnik 1, and the beginning of a new era: the Space Age.

HAD IT NOT BEEN for a collision with a tree by a vodka-sodden driver on the outskirts of Moscow, Russia would not have put Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite, into orbit around the Earth when it did. Sadly, history does not record the driver’s name.

It was 1957, and the Soviet Union’s brilliant but secretive rocket genius, Sergei Korolev — known to the West for decades only as ‘the Chief Designer’ — had been struggling against a lack of interest from the military and the Politburo in making the Soviet Union the first to launch ‘a little Moon’, as he dubbed it.

His explicit focus, he was told by the leather-clad apparatchiks who visited the desert plains of his secret launch site in Kazakhstan, should be to “build ICBMs”: intercontinental ballistic missiles that could hurl atomic bombs across continents.

These were the nascent days of the Cold War, when an arms race was heating up between two competing ideologies: market capitalism as proffered by its global champion, the United States of America; and the command economy of communism, best exemplified by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), a one-party state with a capital in Moscow, home to the largest republic, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

At the time, it was not clear who might emerge the victor in this drawn out contest for global pre-eminence. In the USSR, led by the more liberal Nikita Khrushchev, who had taken over four years earlier following the death of strongman Josef Stalin, industrial production was expanding fast, threatening to overtake the USA, which was itself undergoing a post-war boom.

While the world had been at peace for more than a decade after the calamity of World War II, tensions were ratchetting up. The USSR had detonated its first hydrogen bomb in an atmospheric test in 1953, formed the Warsaw Pact in 1955 — a collective defence treaty between the USSR and the other Eastern Bloc socialist republics of Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania — then sent tanks into Hungary the following year to forestall a democratic drift.

Meanwhile, in the United States, senator Joe McCarthy had begun a political witch-hunt for an imagined communist conspiracy in Washington DC, while the CIA was helping to overthrow elected governments in Iran and Guatemala (1953 and 1954 respectively) for being too pro-Soviet.

At the same time, there were efforts to defuse tensions and encourage global cooperation. The most visible such initiative was a declaration by the United Nations in 1953 of the International Geophysical Year, to begin in July 1957; it called on all nations to take part in the largest set of coordinated experiments and field expeditions of the atmosphere, continents and oceans ever.

Among the grandiose list of proposals was that a satellite be placed in Earth orbit to “allow scientists … to take part in a series of coordinated observations of various geophysical phenomena”.

Both superpowers reacted to the United Nations’ call: in 1955, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower had publicly committed to launching a satellite during the IGY; on hearing of this, the Soviet Union, too, had started making plans, although behind the scenes.

By the time 1957 came along, tensions were still evident: both the U.S. and the USSR had bombers continually in the air, laden with nuclear weapons and on constant rotation, poised to retaliate against any sign of nuclear strike by the other. The U.S. Strategic Air Command alone operated a fleet of more than 3,000 planes and was averaging 430 aerial refuelings a day.

But behind the scenes, both superpowers had been working to develop ICBMs which, in their silos underground, could lie ready to launch in case of an attack; they would be a lot less expensive, and less prone to triggering an accidental thermonuclear war.

In the USSR, Korolev had been evolving what would become the R-7 Semyorka, a 34-metre-tall two-stage rocket weighing 280 tonnes. Powered by liquid oxygen and kerosene and boosted by four strap-on liquid rocket boosters, it was theoretically capable of delivering a payload up to 8,800 km away.With steady funding from 1953 onwards and the Soviet military behind him, the R-7 advanced with great speed.

But the first launch on 15 May 1957 was a failure, the rocket crashing 400 km from the site — calling into question the whole program. Pressure on Korolev and his team was immense: so it was a relief when, on the next test, on 21 August 1957, the R-7 flew over 6,000 km — becoming the world’s first ICBM.

With the success of the R-7 under his belt, Korolev saw an opportunity to advance his cause to launch his ‘little Moon’. For Korolev and his American counterpart, Wernher von Braun, developing rockets was more about exploring space than building missiles. But both were hampered by a military that was at best uninterested and, at worst, openly hostile to their cause.

The task of launching the first American satellite, as mandated by Eisenhower, had been given to the U.S. Navy — even though von Braun’s team had, by September 1956, set a world record by launching a Jupiter-C rocket more than 1,000 km high and a downrange distance of 5,300 km.

Von Braun could have placed a satellite into orbit there and then; but he had been ordered to fill the upper stage with sand ballast. There would be no “accidental satellites”, he was warned: the U.S. Navy was developing a rocket and would launch a satellite, Vanguard 1, some time in 1957.

Korolev, reading of von Braun’s Jupiter-C flight, mistook it as a U.S. attempt to launch a satellite that had failed. The Soviet Union would be beaten, even though he had a rocket ready to fly. But he was also constrained by bureaucracy: design of the Russian satellite, known as ‘Object D’, was led by the USSR Academy of Sciences, responsible for the research instruments, and the Ministry of Defence Industry’s primary design bureau outside Moscow, assigned the task of building the satellite. Weighing more than 1,000 kg, it would carry up to 300 kg of instruments and be launched sometime in 1957.

But work on ‘Object D’ had been repeatedly delayed; as a result, the launch date had now slipped to April 1958. Fearing the Americans would soon launch again and steal the USSR’s glory, Korolev decided to push his luck: he ordered Object D, ready or not, delivered to his launch site immediately.

That’s where our driver comes in. The Ministry of Defence Industry’s facility, glad to be rid of the bulky and troublesome package, assigned a truck driver to deliver it to the airport. Rocket engineer Boris Chertok recalls the drunken man driving “like a maniac”, unaware of the precision instruments aboard, and finally crashing into a tree.

When Korolev finally laid his eyes on the bulky satellite, he was incandescent with rage. It was too big, too complicated and, now, too damaged. One of his engineers, Mikhail Tikhonravov, suggested they instead fly a radio beacon: a simpler, smaller package with just antennas and a transmitter, weighing much less. Then they could beat the Americans.

Engineer Nikolai Kutyrkin was given the task of designing a ‘simple traveling companion’, or ‘prosteishy sputnik’, while Georgy Grechko — a future cosmonaut — was appointed to calculate a launch trajectory. It was eventually dubbed Sputnik 1.

On 4 October 1957, the R-7 rocket rose on a bed of flames and disappeared into the night sky. When it was due to fly overhead on its first orbital pass, the engineers and dignitaries crowded into the radio room and waited. Finally, it came — a faint sound, growing steadily louder and clearer as it streaked overhead: beep, beep, beep.

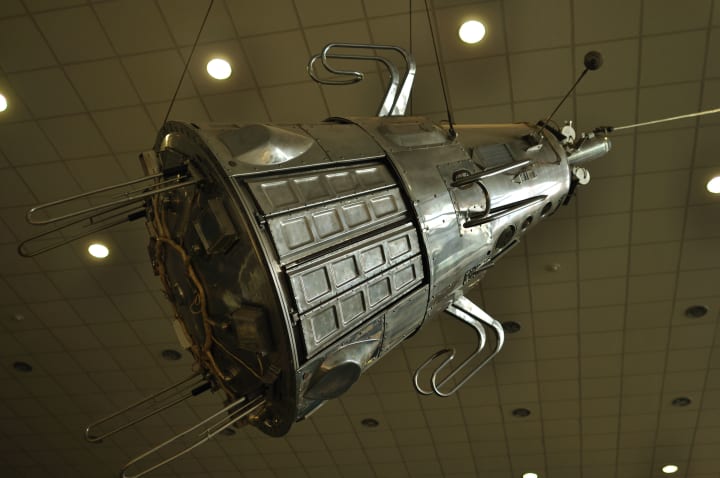

Sputnik 1 was now in orbit. It went on to broadcast for three weeks until its batteries died, then orbited silently for another two months and then fell back into the atmosphere. A polished metal sphere just 58 cm in diameter, it had four long antennas to broadcast radio pulses, orbiting at a 65° inclination that made its flight path cover virtually the entire inhabited Earth, its signal easily detectable by ham radio operators.

Even just tracking and studying Sputnik 1 from Earth gave scientists valuable information: the density of the upper atmosphere could be deduced from the drag on its orbit, and the propagation of its radio signals gave data about the ionosphere.

The U.S. Navy, plagued with launch failures, was shocked; von Braun was furious, and the American press went ballistic. The first artificial satellite was now a reality.

Like this story? Please click the ♥︎ below, or send me a tip. And thanks 😊

About the Creator

Wilson da Silva

Wilson da Silva is a science journalist in Sydney | www.wilsondasilva.com | https://bit.ly/3kIF1SO

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.