History of the 1st Year of Coronavirus

It Ain’t Over Yet

One year ago today, on March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the rapidly spreading Coronavirus a global pandemic.

It had noted in early January last year a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China. Soon thereafter, it reported in their Disease Outbreak News of a new virus.

What happened then?

Lots of things happened that day. The President addressed the nation from the Oval Office. Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson had tested positive on the set of a film in Australia. The NBA, reeling from its own infections, would be the first pro sports league in America to suspend its season. Schools shut down, streets emptied, toilet paper disappeared from store shelves, airplanes flew with empty seats, people did Work From Home, hospital beds filled up, essential workers became heroes.

Remember how we were encouraged last year to “Flatten The Curve” so that hospitals would not be overwhelmed? Two weeks should do it… OK, another two weeks. Did we say weeks? We meant months.

It has lasted longer than almost anyone could have predicted, well past the end of 2020…

It changed work plans: we canceled the remainder of a 9-city training tour I was leading.

It changed vacation plans: no summer trips to Europe, no cruises to Hawaii.

It changed family plans: couldn’t visit loved ones for fear of exposure.

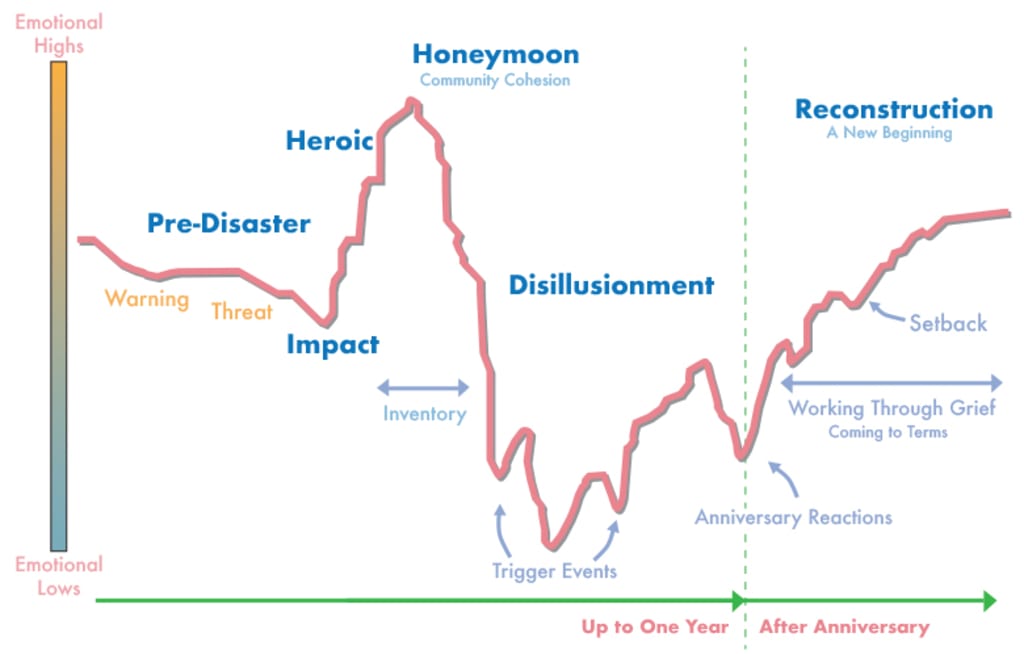

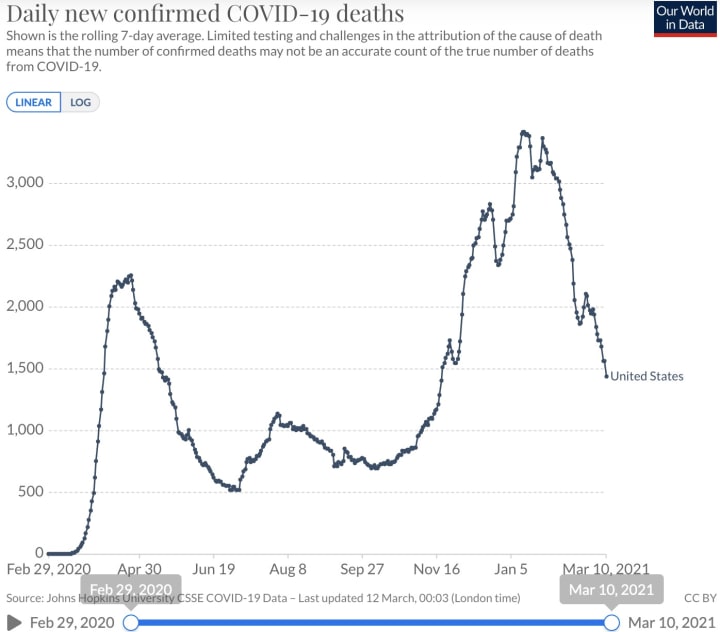

It has indeed been a roller coaster experience, as the picture at the top depicts, showing how the Disaster Technical Assistance Center’s manual is used by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services workers.

What have we learned about Coronavirus?

There are (at least) three things we had wrong about Coronavirus during this first year:

1. It’s Zoonotic

The original narrative was that the virus came from a wet market in Wuhan, China. It was believed to have jumped from bats to pangolins to humans. The WHO just concluded a study in China and found no evidence of this origin. The hypothesis of the virus having escaped a lab is increasingly given equal credence, with equivalent amounts of no evidence.

2. No Variants

Previously, it appeared that Coronavirus was stable, not a shapeshifter like the flu virus. But now we’re seeing several major variants worldwide that are more infectious, and in some cases, are becoming the new dominant variant.

B.117 — first identified in the U.K. — is feared to be the predominant variant in the U.S. by the end of March

B.1.351 — initially identified in South Africa — where it’s the primary variant, numerous vaccines were less effective at preventing infection: Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine dropped from 72% efficacy in the United States to 57% in South Africa. There’s also concern it may allow reinfection of those who’ve already had Coronavirus.

P.1 — first identified in Brazil — is prevalent in parts of South America

B.1.427/B.1.429 (initially identified in California)

B.1.117 is 30–50% more transmissible (and perhaps more deadly) than the initial strain. The CDC recently issued a precautionary message warning that B.1.117 would be the predominant variant in the U.S. by the end of March. This has broken the statistical modeling that predicted when we’d achieve herd immunity. Some scientists express concern about a 4th wave surge.

The Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine is claimed to neutralize the new variant spreading in Brazil, New England Journal of Medicine on Monday. Nevertheless, both Pfizer and Moderna, the first two vaccines available that use mRNA, are talking about developing a third booster to come after the required second shot to address the new variants.

3. Vaccine panacea

The previous administration’s Operation Warp Speed promised rapid distribution of tens of millions of doses to states by the end of 2020. But then the preparedness to distribute those to community vaccination locations varied by state. Alaska has fully vaccinated over 15% of its population, Utah has only vaccinated 6.5%.

Population, geography, infrastructure, logistics, and political leadership are all factors that impact a state’s ability to roll out vaccination effectively. In the same way that Coronavirus was politicized, it is sad to see Coronavirus vaccination being politicized. I mentioned in my previous article on Coronavirus: How Will It End several of the challenges of universal vaccination.

The current administration has said it would purchase an additional 100 million single-shot vaccine doses of the recently approved Johnson & Johnson vaccine. Merck, usually a competing pharmaceutical company, has said they would aid J&J in the manufacturing. The production bottleneck is filling the vials (bottles) with the vaccine. Current manufacturing processes cannot make that go faster without using more lines of production.

Where are we now with Coronavirus?

The global death toll has grown to more than 2.6 million out of more than 117 million known cases. Almost 20% of those deaths, over half a million, come from the US.

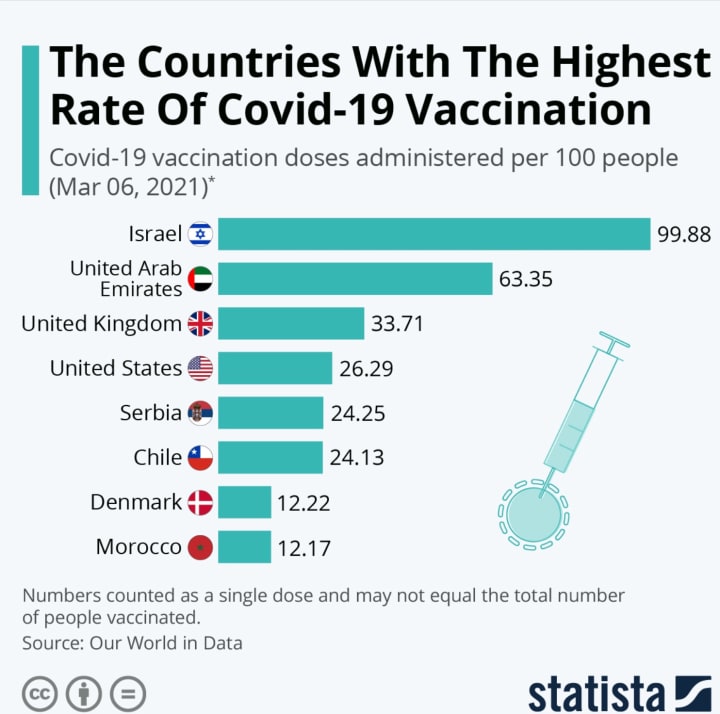

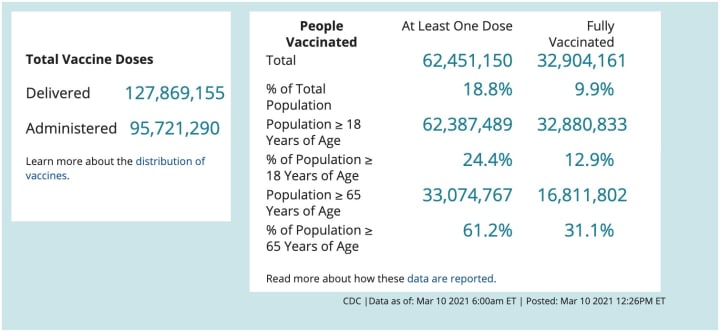

So far, 320 million vaccination doses have been administered globally. Israel leads in the percentage of its population vaccinated, at more than 50%. And despite struggling to contain the virus, the U.S. leads the world in terms of absolute doses administered at almost 94 million, or about 30% of the global total. Roughly 33 million people in the US are fully vaccinated, about 10% of the population.

Congress has approved $5 Trillion (with a “T”) in emergency aid funding for Americans over the last year. By comparison, President Obama’s relief package following the 2008-9 Recession was $840B.

Financial impact of Coronavirus

AMC Theatres reports a full-year loss of $4.58B amid the global pandemic, almost $1B loss this quarter.

Tourism has been down worldwide:

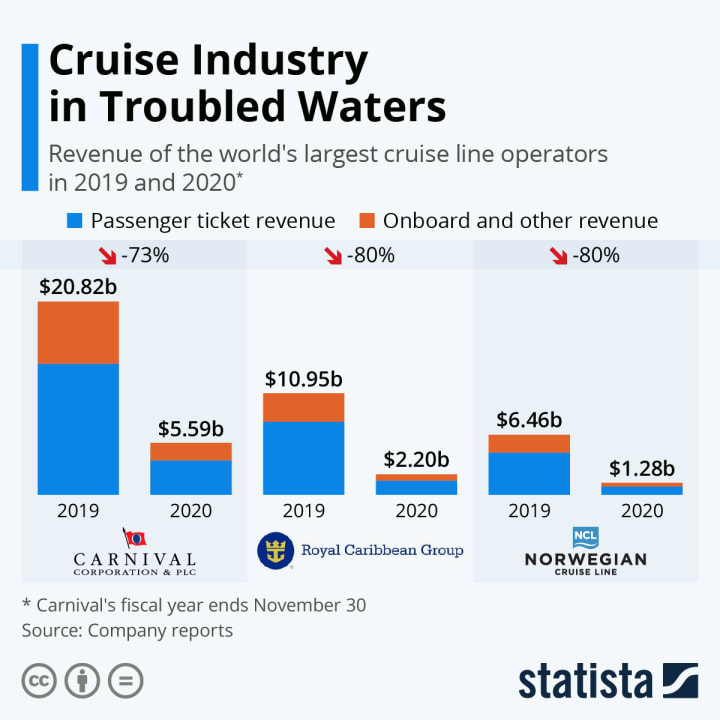

Major Cruise lines have been pushing back their sailing dates:

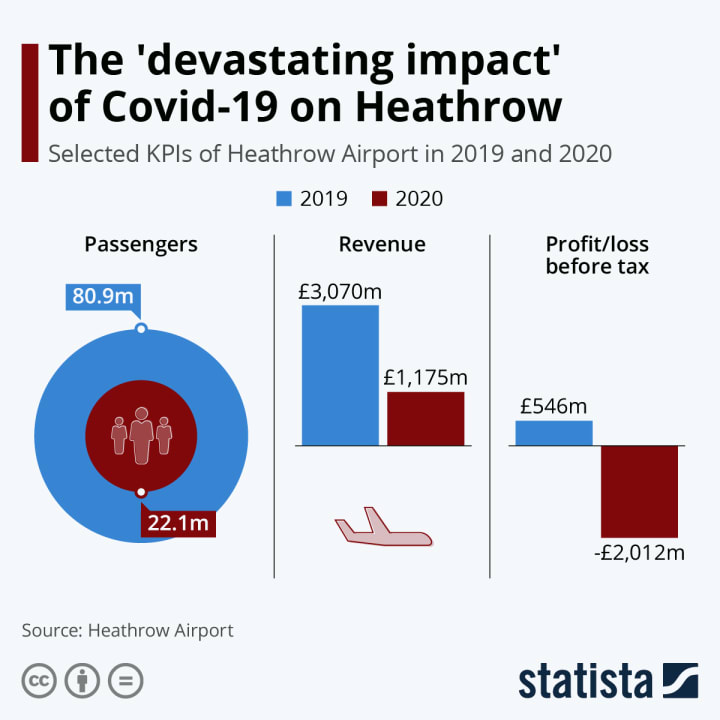

International airports have been impacted financially:

Going forward with Coronavirus

This week the CDC issued new guidance for those in the US who had received their full vaccination regime. It was not as relaxed as we had hoped, despite Coronavirus cases beginning to drop dramatically in mid-January, predictably two weeks after the holidays. There is an expectation this year of an “almost-normal summer,” but we hoped that last summer.

Despite promises from the three leading vaccine providers of a massive number of doses, previous Phase 3 testing for FDA approval did not include children. Pfizer has been given emergency authorization for use for people 16 and older. Moderna has been approved for those 18 and older. The new Johnson & Johnson vaccine was tested on people 18 and older. These companies are only now testing for younger people. While universal adult vaccination is a good thing until children have the vaccine safely available to them, I don’t expect to see guidance lifted on the three prophylactic practices recommended: masks, social distancing, hand washing.

So, how does Coronavirus end?

Any pandemic ends when the virus is no longer prevalent worldwide or in multiple countries/regions. That can occur in a variety of ways:

Medical: A vaccine or an effective treatment is developed – this would be the most desirable option. Think of polio – an epidemic, not a pandemic – which came to a medical end with a vaccine. But the vaccine distribution and vaccinations need to be near-universal to achieve herd immunity.

Herd immunity: Infection and death rates plummet – also considered a medical end. That’s how the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 ended – those infected either died or developed an immunity.

Social: People simply get tired of living in fear and learn to live in a world with the disease. This is considered a social ending, which is not an actual end since the disease itself doesn’t go away. In this situation, the disease may continue to spread, which can delay the medical end. In some cases, it becomes endemic: a constant presence in a specific location. Malaria is endemic to parts of Africa.

A doctor friend of mine has said, somewhat sardonically,

“We’ve made our peace with influenza deaths”

meaning we’re willing to accept the 20,000 to 40,000 deaths that come each year with the common flu in the U.S., in the same way that we’re unwilling to lower the speed limit to prevent thousands of automobile fatalities.

Coronavirus Today

Yes, we grieve for the last year. But you and I are still here. Coronavirus case numbers are fewer, and the death rate is dropping. Let’s take hope. Keep the faith.

Bill Petro, your friendly neighborhood historian

If you enjoyed this article, please consider leaving a comment. Subscribe to have future articles delivered to your email.

About the Creator

Bill Petro

Writer, historian, consultant, trainer

https://billpetro.com/bio

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.