‘Hello From Earth’: The Unlikely Story of an Interstellar Message

This is the improbable story behind Australia’s first attempt to contact an extraterrestrial civilisation.

IMAGINE YOU could send a text message to an Earth-like planet far away, a planet that could well be home to an alien civilisation. What would you say?

That’s exactly the question people faced a decade ago. In an Australian project called HELLO FROM EARTH, almost 26,000 people wrote a 160-character message that was sent to Gliese 581d, an Earth-like planet 20 light-years away. That powerful transmission, sent by NASA, has now passed the halfway mark on its long, lonely journey through the silent cosmos.

And it began in a café in inner Sydney in May 2009. It was the International Year of Astronomy and Simon France, then head of the Australian Government’s National Science Week initiative, was looking for ideas for an event that would spark national interest in astronomy later in August of that year. I was editor-in-chief of Cosmos magazine, and France was discussing ideas over lunch with me and publisher Kylie Ahern.

What he needed was a really big idea, one that could go viral, he said. It had to be centred on astronomy. And social media should play a major part.

Maybe it was his juxtaposition, but a thought popped into my head. “How about ‘Twitter to the Stars’?” I quipped.

His eyes widened. “What do you mean?”

“We collect short messages from the public during Science Week,” I said confidently, making it up as I went. “Then at the end, we transmit them to the nearest habitable planet beyond our solar system.

“Each message would only be as long as tweet, so they’d be short enough that we could package them into a single transmission using one of the big radio telescopes,” I proffered.

“Can we do that?” France asked. “Where would we send it?”

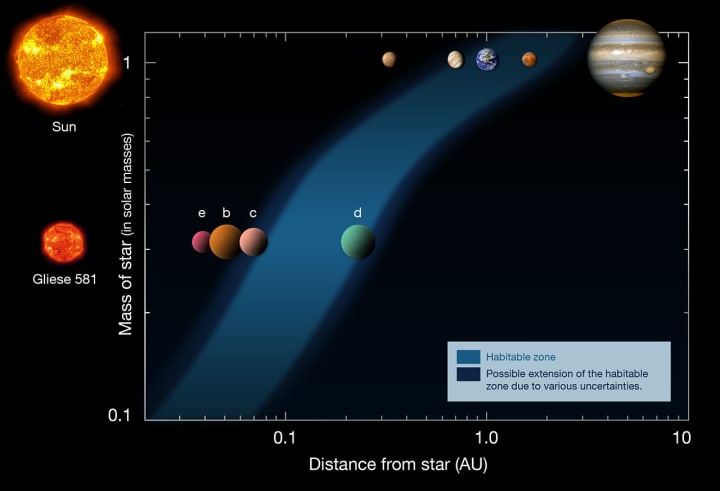

“Technically, it’s not a challenge, and we at Cosmos could do it,” I said, probably a bit too nonchalantly. “And there’s a great candidate: Gliese 581d, a ‘super-Earth’ orbiting in the habitable zone of its parent star, which may well have oceans. It’s 20 light-years away, so people taking part will get a real appreciation of how big the universe is.”

France left the lunch enthusiastic, if a little sceptical, but asked us to look into it and come up with a proposal. “Could we really do it?” Ahern later asked. “I think so,” I said. “But we’ll need to convince NASA to help.”

All of this was true.

The Gliese 581 solar system, 20.4 light-years away, is known to consist of at least four planets; one, the ‘d’ in Gliese 581d, is thought to be a rocky world almost seven times the mass of Earth. Its orbit is within the habitable zone — where temperatures are just right for surface water to exist — and therefore can potentially support life. First detected in 2007, studies announced in April 2009 indicated it may have one or more large oceans.

And NASA uses radio dishes in Australia every day to chat with far-flung spacecraft travelling the outer reaches of the solar system, like Voyager 2 and Pioneer 11. These tiny craft are billions of kilometres away, so NASA uses massive signal strength to reach them; hence, transmitting a clear message to a star just 20 light-years away was entirely feasible.

SO BEGAN THE FIRST interstellar message ever sent from Australia. In the months that followed, I had many conversations with sometimes quizzical senior Australian scientists, leading international astronomers and U.S. government officials, negotiating terms and agreeing to specifications. I often invoked the name of the then Australian Science Minister, Kim Carr — his press secretary said I could, although he declined to provide a written endorsement from the minister. Nevertheless, I persisted.

Did we need international approval to transmit a message? The International Astronomical Union — which has the authority to name planets and other celestial bodies — said they had no jurisdiction, and no objection. They directed me to International Academy of Astronautics, which has a permanent group on SETI, or the search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

While the academy did not have a policy position on sending messages from Earth, they do claim authority over extraterrestrial messages arriving on Earth. Since 1989 the academy, relying on Article XI of the United Nations Outer Space Treaty, has mandated that “No response to a signal or other evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence should be sent until appropriate international consultations have taken place.” However, that mandate is not legally enforceable.

You can understand why they created it, though: if ever a signal is detected, you can’t just have anyone with a high-gain antenna suddenly answering back.

But who speaks for Earth? Well, that turns out to be the SETI Post-Detection Subcommittee, which at the time was chaired by astronomer Paul Davies of Arizona State University — who just happened to be an old friend and occasional writer for Cosmos.

“What do you think?” I asked in an overnight phone call after explaining HELLO FROM EARTH. “Will we breach any regulations in the scientific community?”

“Well, there’s no statute covering interstellar messages, and no-one has jurisdiction over transmissions,” Davies said from his home in Tempe, Arizona. “But it will upset some people.”

I asked why. “Because some scientists believe that sending such messages alerts potential extraterrestrial civilisations of our existence, which they consider unwise and potentially catastrophic,” he said.

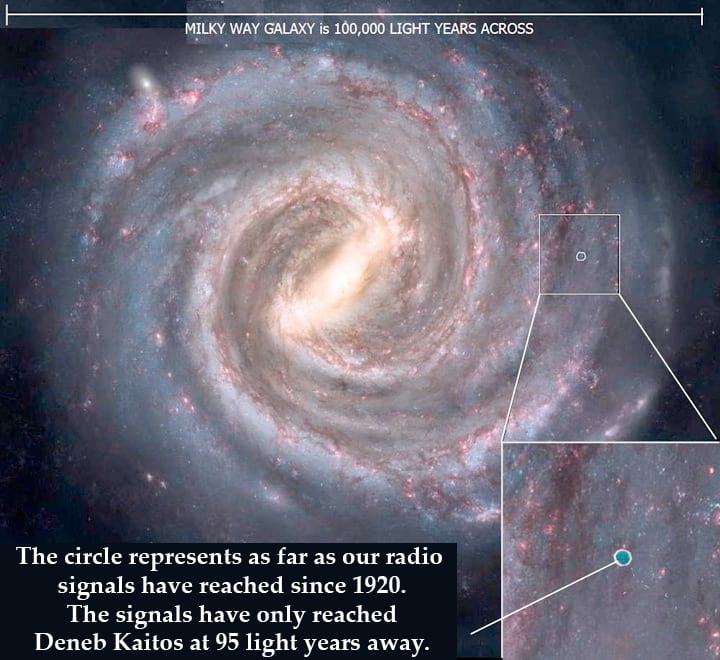

“Seriously?” I chuckled a little awkwardly. “What, it might bring on an invasion? But we’ve been broadcasting our existence since the 1930s, haven’t we? Television transmissions from every city go into space every day, blanketing the whole sky as the Earth turns. Military radar is even more powerful, and probably detectable for more than 100 light-years, no?”

“That’s largely true. Nevertheless, there’s a debate. It’s a minority of the scientific community, but it exists.”

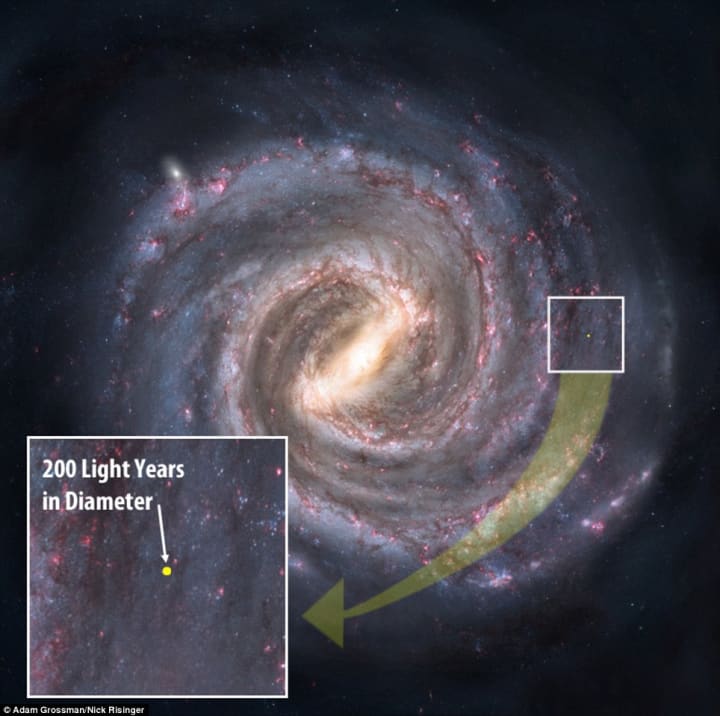

Did he have any concerns, or any objections, though? Davies said the academy had no official opinion on interstellar messages. And personally, he didn’t object. “There’s a ‘radio bubble’ emanating from Earth in all directions, and it’s almost 200 light-years in diameter. Extraterrestrials with technology advanced enough to threaten us would also have much better antennas, and would already know we’re here.”

Again, no jurisdiction, and no objection.

Just the infinitesimal chance that HELLO FROM EARTH might trigger an invasion fleet from Gliese 581.

Eventually, my proposal made it to the desk of NASA Administrator Charles Bolden Jr. And eventually, he approved it — just eight days before National Science Week was due to start.

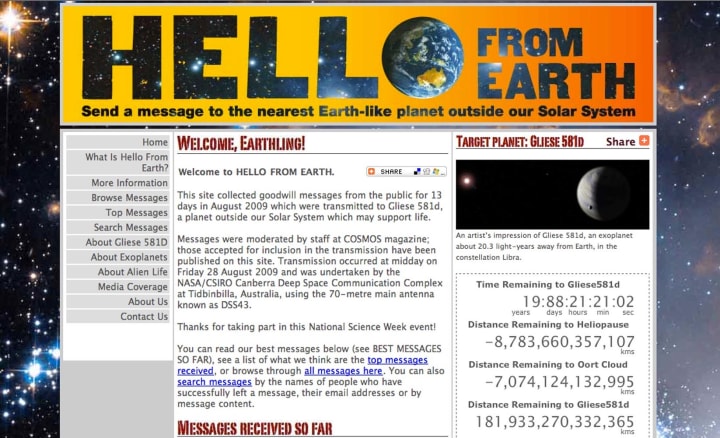

In those eight days, we hired a company to fast-build a website that allowed people to register via email and upload messages that would appear on the HELLO FROM EARTH website, as well as be collected for transmission.

We leased a dedicated server at a large-scale data centre in Sydney, created content pages about the Gliese 581 system, about the 350 planets beyond our solar system, or ‘exoplanets’, that had been discovered up until that time (compared to some 4,000 now), and wrote background on the scientific thinking surrounding extraterrestrial life.

And we assembled a team of 10 moderators around the world so that the messages uploaded could be read 24/7 and quickly accepted or declined.

ON 12 AUGUST 2009, Science Minister Kim Carr walked up to a computer screen and, tapping on a keyboard, wrote the first interstellar message ever sent from Australia: “Hello from Australia on the planet we call Earth. These messages express our people’s dreams for the future. We want to share those dreams with you.”

At least, he tried to. News outlets around the world had already trumpeted the initiative, some breathlessly, like The Daily Mail: “Is there anybody out there? Australian minister leads nation in contacting planet Gliese 581d”; others jovially, like The Sydney Morning Herald’s “Dear alien: Can I add you to Facebook?”. Launch time had been 10am, but the event was running a few minutes late. Meanwhile, the server was being overwhelmed by thousands of people trying to login. The minister couldn’t upload his message.

The smile drained from Carr’s face, and his press secretary turned to me in fury, while I made frantic calls to Dean Turnbull, who was then lead developer at eNerds in Sydney and who’d assembled the site in record time. “Mate, it’s bonkers,” he told me. “The server is getting absolutely flogged!”

A few minutes later, Carr was cleared to go and pressed ‘send’ on his message, and there was a round of genial applause from the small crowd. He was followed by then Chief Scientist Penny Sackett, who wrote: “Our observations indicate that your planetary system is a low-mass star orbited by at least four planets, can you confirm?”

Wow, I thought. Even if there’s a civilisation on Gleise 581d and they quickly decode the signal, understand English and dash off a swift reply, it’ll be 2051 before she gets an answer.

The next few days were a blur. We got back-to-back calls for radio interviews from around the world, while visits to the HELLO FROM EARTH site spiked higher and higher. Cosmos staff halted work on the next issue to help moderate the uploaded comments, while I arranged to lease a second dedicated server to help handle the booming web traffic.

The messages that came in were an insight into people more than anything: there was a lot of humour, sure, but also heartfelt yearning:

“If you come to Earth, look into: music, the beach, ice cream, hugs, family, love, dancing, cheese, trampolines, friendship, books and dreams. Just for a start.” — Tamasin, Richmond, Australia

“Greetings from a girl on Earth who, every so often, looks up at the night sky and waves hello in the hope that someone on another planet is doing the same.” — Sophie, Longmont, Colorado, United States

“Here, warmth is one of our greatest pleasures. Warm sun on our skin, warm food in our bellies, warm contact with loved ones. I hope we can share this with you.” — Crystal Rice, Cannonvale, Queensland, Australia

“Hi there. Sorry about the Outer Limits; hope you enjoyed I Love Lucy. Have you got all our missing socks? Love, Earth.” — Fred Mason, Roberts Creek, Australia

The Internet being global, there was no easy way to limit submissions to Australians. Plus, it would have been very uncool: we were, after all, doing it to celebrate the International Year of Astronomy, which is itself a global enterprise — how could we deprive any citizen on the planet the opportunity to send a personal message to another potentially habitable world?

It was also a more innocent time, when trolls were not as plentiful: Twitter was only three years old and had 18 million users posting 27 million tweets a day — compared with today’s 330 million users posting 500 million tweets a day. Sure, we occasionally received some awful slurs and unpleasant comments — but less than 1% of the uploaded messages violated the standing rules.

And yes, there were rules. Some were just common sense: use only ASCII plain text, and list no email addresses, URLs or HTML tags (yes, the Internet is just about everywhere these days, but it is limited to this planet). We also stipulated that messages would be moderated and rejected if deemed inappropriate — that is, if they contained profanity, racism, derogatory comments or personal attacks.

But NASA also insisted on a high level of decorum: nothing seemingly sexual or suggestive (including the word ‘breast’!), no ribald or risqué humour, nor anything remotely aggressive. Hence, one Perth resident who posted “Hey, what’s up? All your base are belong to us” — was rejected.

We tried to explain to NASA that this was actually a gaming joke: a popular Internet meme based on a broken English phrase in the opening of the 1989 video game Zero Wing. But no, they wouldn’t budge.

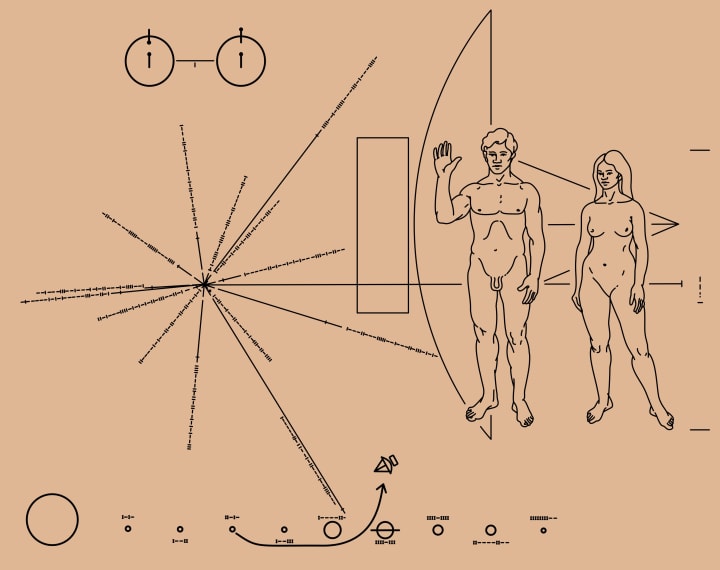

To be fair, NASA had reason to be cautious. In 1973, they attached a gold-anodised aluminium plaque to the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 space probes, which would become the first to leave the solar system, with an illustrated message in case either was found by extraterrestrials. It depicted two hydrogen atoms, an array of lines and dashes — a kind cosmic address for our Sun on the radio spectrum of the galaxy — as well as an illustration of a naked man and woman, showing what our species look like.

Soon, NASA was receiving complaints from members of Congress, and newspapers ran letters objecting to NASA “exporting pornography to the stars”.

But the biggest objection was one I hadn’t seen coming: we asked that all submissions be in English, so our moderators could read each message and determine if it complied with the rules. This was, however, seen as conspiracy — especially by French and Mandarin speakers — to establish English hegemony and portray it to aliens as the official language of Earth. There are way more native speakers of Mandarin Chinese and Spanish, they said. Very true.

One of the messages rejected was from Eric Abetz, then Liberal opposition spokesman on science: “The Coalition dreams that by the time you receive this message in 2029 Australia will be free of Labor debt. Sadly, we’re not holding our breath!”

His message was declined, with an explanation that it contravened rules around ‘derogatory comments or personal attacks’ and invited him to try again (each registrant was given five attempts). Abetz instead issued a media release: “It seems that the view has been formed that the inhabitants of Gliese 581d would be so disturbed to hear about Labor’s $315 billion debt that its existence should be kept from them!”. He later interjected in the Senate when Carr spoke during Science Week, eventually prompting Carr to blurt: “Senator Abetz, these are genuine messages!”

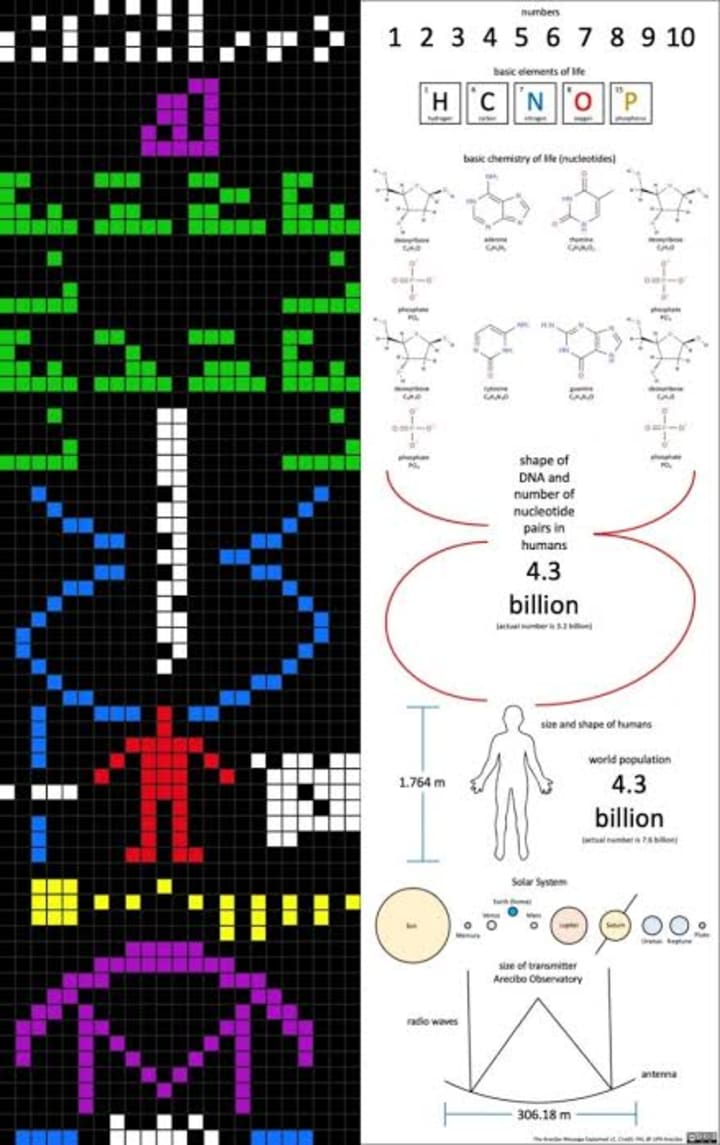

THE FIRST INTERSTELLAR message — or the first intentional one, at least — was transmitted by the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico in 1974. It was aimed at the M13 globular star some 25,000 light years away to mark the refurbishment of the telescope. The three-minute message was a rudimentary pictogram consisting of 1,679 binary digits, transmitted at a frequency of 2,380 MHz with a power of 450 kW.

I had read about this many years before, and it popped into my head that May afternoon in 2009 when I proposed the project.

But it turned out that I wasn’t the only one who had thought it a great idea: HELLO FROM EARTH was actually the 20th interstellar transmission initiative, and there have been another 11 since. While ours was aimed at a solar system in the constellation of Libra, others have targeted more than 20 star systems in 19 constellations, plus the M13 globular star and at the Andromeda galaxy. Four stars had been targeted more than once.

The second message, sent by astronomers at the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan in 1983, was aimed at Altair, the brightest star in the constellation of Aquila, and arrived in 2017. It consisted of 13 binary-encoded images (71 x 71 pixels each) depicting a diagram of our solar system, the location of Earth, the known chemical elements and the basic structure of DNA. Since Altair is 16.7 light-years away, if there are Altairians and they decode it, the earliest we’ll hear back from them is 2034.

Some initiatives have been serious attempts to hail alien civilisations, but most have been science communication exercises aimed at fostering public engagement, like ours. One was sent in 2008 by a large 70-metre dish outside Madrid to commemorate the 50th anniversary of NASA. It also happened to be the 40th anniversary of the recording of the Beatles song, “Across the Universe”, hence this was selected for transmission — with approval from Paul McCartney, Yoko Ono, and Apple Records. The song was transmitted to Polaris, which is 431 light years away and unsuited for life, as it is a triple star system anchored by a yellow supergiant.

So, we might not have been as novel as we thought, but it was still incredibly cool: we really were going to transmit messages to the nearest Earth-like planet outside the solar system — a planet that could well be an ocean world like ours.

At night, while cradling my laptop and moderating the incoming messages, I occasionally thought to myself: “Wow. We really are doing this!”

AT 5PM ON MONDAY 24 August, the website stopped accepting new messages. We’d finished the 12-day run with 25,880 messages successfully uploaded.

The site had generated 1.24 million page views from 199 nations and territories — from Afghanistan to Antarctica, from Morocco to Macau. HELLO FROM EARTH had featured in more than 1,000 newspapers, in scores of languages, and 10,723 blogs had mentioned it and were now linking to the site.

We merged the messages into a single document: it ran to 1,003 pages and 524,704 words. This was passed on to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, who encoded them into a binary signal that could be transmitted.

They also needed to establish where to point the radio dish.

This was no mean feat: engineers need to not only point the dish exactly where Gliese 581d would be on its orbit around its parent star when the message arrives, but figure out where the whole solar system would be 20 years and 145.7 days in the future.

That’s because our galaxy is rotating, and all its stars move around the centre. Our Sun — which is about 24,000 light-years from the core of the Milky Way — orbits at about 220 km/second, taking 230 million years to make one revolution.

To cap it off, each star tends to bob and ebb in the cosmic ocean, often displaying its own idiosyncratic motion. Hence, extremely careful calculations have to be made about where the Gliese 581 star system will be, as well as establishing where along its orbit the fourth planet is located when the signal arrives.

When you think about it, it’s astonishing that we can do this. Adding to the fact that it’s already mind-boggling we were sending goodwill messages from a random selection of humans to a potentially habitable planet that might have a technical civilisation. Granted, that chance is highly unlikely. But it’s not zero.

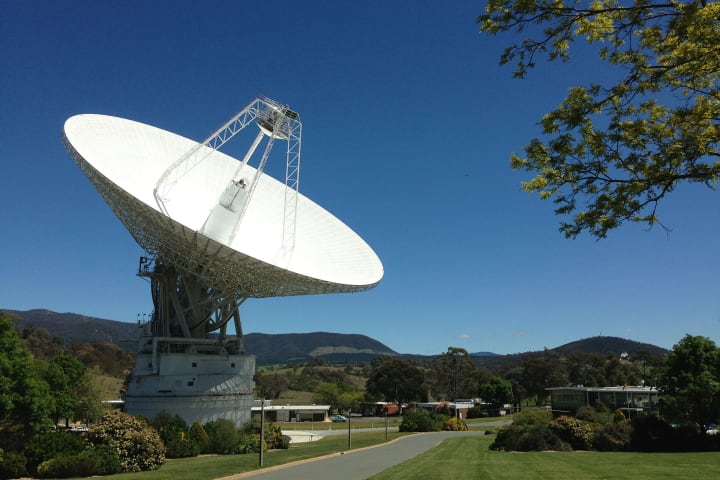

THE LARGEST STEERABLE parabolic antenna in the southern hemisphere is DSS-43, a 70-metre dish weighing 3,000 tonnes at the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex (CDSCC) near the Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve.

It’s part of part of NASA’s Deep Space Network — the other two facilities are outside Madrid, Spain and Barstow, California — which together are the largest and most sensitive scientific telecommunications system in the world.

DSS-43 was scheduled to transmit the HELLO FROM EARTH message on 28 August 2009 at 11:30am, and I drove down for the event. By pure luck, indigenous students from the Karalundi College in Meekatharra, 821 km northwest of Perth, were visiting that morning, and they joined us to watch the colossal dish gently slew toward Gliese 581d.

The packaged messages were transmitted at a frequency of 7.145 gigahertz and a power of 18 kilowatts, and repeated twice over two hours “at a power level and frequency that will be obvious to anyone who might be listening” the then director of the CDSCC, Miriam Baltuck, told the assembled crowd near the foot of the dish. “That’s equivalent to using the combined power of over 300 billion mobile phones at once.”

We watched for a while. It seemed fitting that the first interstellar message from Australia was being witnessed by indigenous Australian children, representatives of a culture twice as old as the time it takes light to travel to Earth from the centre of the Milky Way.

HELLO FROM EARTH was probably just a ‘message in a bottle’ tossed into a silent interstellar ocean, a cosmic ‘cooee!’ shouted into a long and empty night. But if a reply did eventually come, it would arrive decades from now — and these students would be around to see it.

Like this story? Please click the ♥︎ below, or send me a tip. And thanks 😊

About the Creator

Wilson da Silva

Wilson da Silva is a science journalist in Sydney | www.wilsondasilva.com | https://bit.ly/3kIF1SO

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.