Full Skirts, Cinched Waists, and Women’s Rights

Christian Dior’s New Look and its Influence on Second Wave Feminism

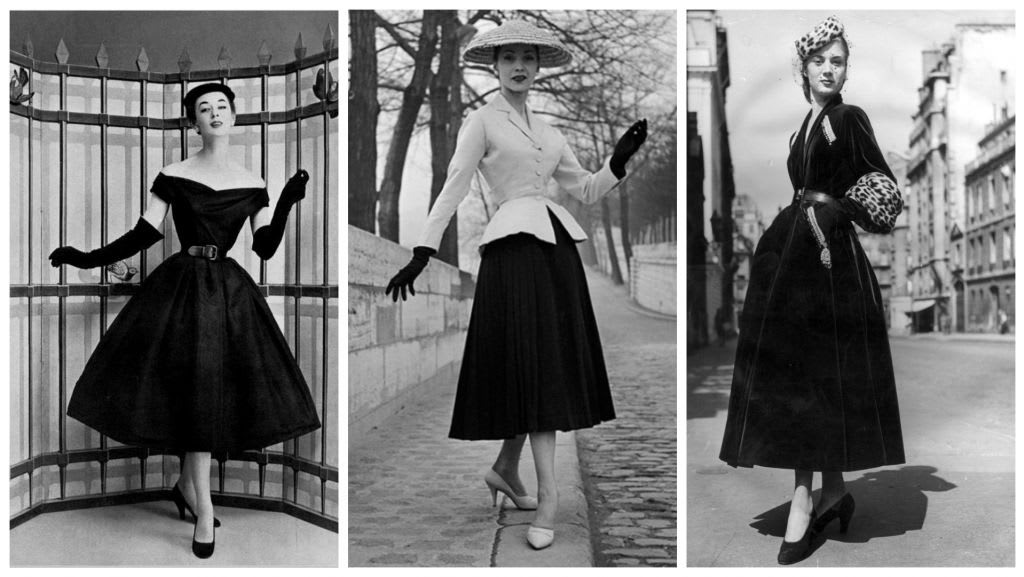

It’s February 12, 1947, the world is rebuilding after WWII, and Christian Dior has just debuted his haute couture fashion line full of voluminous skirts, tiny waists, and padded hips. Completely opposite the rationed and practical styles of wartime, Caramel Snow, the editor of Harper’s Bazaar, excitedly described the designer’s debut collection as a “new look”, thus forever naming the collection and sending Dior into fashion fame. While today we look back and admiringly celebrate the beauty and talent behind the couture gowns, the collection would be a catalyst (albeit one of many) for the second wave of feminism nearly a decade after their debut.

The New Look was exciting, extravagant, and extremely feminine. It was reminiscent to pre-war times where women were not limited to rationed amounts of fabric or notions; a time when women were “allowed” to express luxuriousness and opulence through their wardrobe. Dior dropped hemlines saying that “short dresses are the fashion of restriction and war and, to me, the symbol of German Occupation”. His cinched waists, full skirts made from 30 or more yards of fabric, and midi length hems rebelled against the bore of the pragmatic styles of wartime.

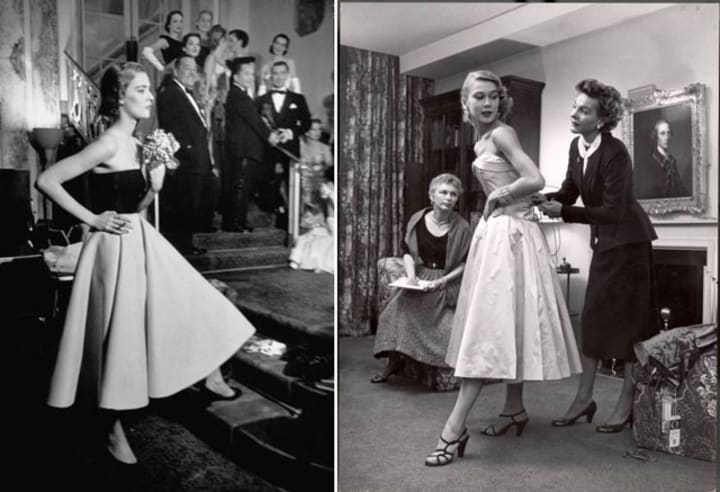

The look was celebrated in Europe and amongst celebrities and socialites (basically amongst those who could immediately afford it), but a large portion of American women, and even men, were outraged. First, the suddenness at which their current wardrobes had become outdated was shocking. It was as if overnight entire closets were deemed obsolete and there was intense pressure to update to this New Look in order to avoid appearing passé and out of stye. Men were reluctant to spend the money on new dresses and shoes for their wives (not to mention they had really grown accustomed to seeing the bare legs that the shorter skirts provided, but that’s a whole different issue). The idea of replacing an entire wardrobe was even further exasperated when shoe designer Salvatore Ferragamo, while visiting America with Dior, made an announcement that new shoe styles which flatter the new hemline must also be purchased. His reason was that since the hems of dresses were lower, male attention would now be drawn to the ankle and foot, thus the shoes worn must blend with that…because where male eyes linger on our bodies is the number one reason, we of the simpler sex have for buying shoes…

Cue the cringe.

The second reason Dior found pushback from Americans is because of the blatant regression to the restrictive dress of the Victorian era, something that women, by that point, had spent decades fighting against. While nobody likes to celebrate war time, World War II offered an immense amount of progress for the feminist movement. It pushed women out of the home and into the workforce like never before, and the fashion that was born out of rationing fabrics and buttons gave women the freedom of movement and independence. The sudden shift that resulted by the world’s enthusiastic acceptance of Dior’s New Look forced all of that progress back multiple steps, if not physically, at least emotionally and psychologically. With the tightly cinched waists and full, padded skirts, heavy with yards of fabric, it was as if Dior was erasing the option of practical attire and reinstating this super feminine beauty standard that didn’t allow for much other than placing the woman back into her role at home.

This pressure to replace entire wardrobes and the feeling of threatened independence resulted in the forming of a protest group called the “The Little Below the Knee Club”. They openly and loudly rejected the long hemlines and padded skirts. When Dior visited Chicago shortly after his look debuted, he was met with picket signs that read “Mr. Dior we abhor dresses to the floor” and “Women, Join the fight for freedom in the manner of dress!”. The group even had Coco Channel’s support. The Queen of Comfort Fashion (and sass) herself openly mocked Dior as a designer saying he “doesn’t dress women, he upholsters them”.

Dior was not intimidated by the protests. They seemed to give him even more confidence in his collection, saying that those who were most upset to lose their short skirts would soon be “wearing the longest dresses”. He also felt that American women were overreacting. He didn’t design these pieces to be everyday wear. He meant them as special occasion pieces and while they may be impractical for the workplace or sporting events, “if [American women] knew how to wear it, it is practical”. He also felt that the American mass market designers had gone completely overboard by adapting his designs and marketing them as everyday wear. So, while the protests of an attack on the progress that women had made over the last decade was not wrong, neither really, was Dior. His intention was to create a couture clothing line that celebrated the end of the war, the end of rationing, and the end of the depression of German occupation. He wanted to bring beautiful, extravagant things back into the forefront, add some color and luxury back into the world. His dresses, in his artistic opinion, were a literal rejection of the oppression and depression that World War II pressed upon society for the previous decade. However, that message was lost upon the American woman due to the enthusiasm of the capitalist mass market.

I mean, what else is new?

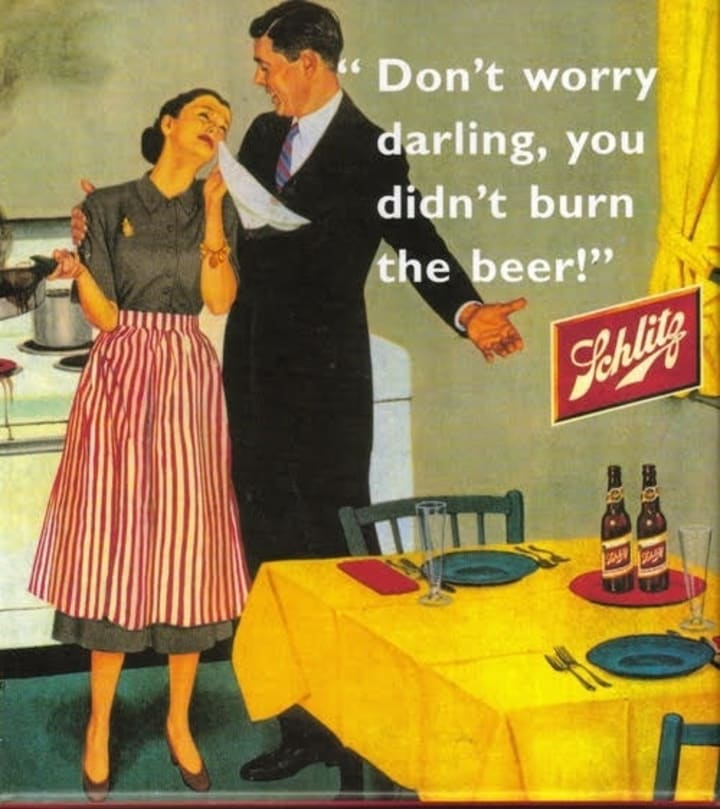

While he may have defended his intention and design theory behind the collection, Dior didn’t do much else to quell the feelings of sexism that had latched onto the movement of his New Look. His you can be mad about it but you’re going to wear it eventually attitude was further exasperated by the absolute peach of a journalist, Samuel Grafton. In an article he wrote for The Charlotte News, he satirically compared the new silhouette to foot binding and fascism, making women secondary to men in everyday life, ultimately stating “you poor darlings, you don’t stand a chance…Stop squakin’ honey, and hold still while they put it on you”. While sarcastic and off-color, he was right in the sense that the movement of Dior’s New Look was shifting society faster and harder than those opposed could fight it and it would be only a matter of time before everyone would be under its influence.

That they were. The silhouette dominated the trends throughout the 50’s, and while Dior refuted the opposition saying his vision was reminiscent of the opulent mood of pre war times, those who protested the look in the name of feminine progress were not wrong about what it meant for women in America. The campaign for re-establishing the roles of the sexes was evident everywhere. Ads and art of the 1950’s depicted women in the style of long, wide skirts cooking and cleaning, taking care of the children or sewing. Women were encouraged to believe that despite all they did and accomplished during the war, their highest calling was, actually, homemaking. Textbooks about “how to be a good wife” were introduced into high school economics classes. Magazines such as “Housekeeping Monthly” printed guides all around the expected wifely duties such as: “have dinner ready on time for his return”, remembering that “his topics of conversation are more important than yours”, “don’t complain”, and “you have no right to question him…a good wife always knows her place”…

She went from bomb factories and fighter jets to stovetops and cleaning gloves, all while being expected to remain pristine in pleated skirts that reached to her shins.

By the 1960’s the Civil rights movement had gained massive traction, and protests against the Vietnam war had swept across America. With the passion of these movements, a second wave of feminism took hold as well. Rejecting the decade long rhetoric of the female role, women pushed for legislative change against workplace discrimination, accessible contraception, and action against sexual and domestic violence. While John F. Kennedy signed legislation in support of the movement, Jackie emulated the look with her signature suits of jackets and matching pencil skirts. With this forward motion of civil and women’s rights, they began ditching the full skirts and cinched waists and adopted slimmer, shorter skirts and dresses, pants, and burned their bras…

…And yet, the hourglass shape of Dior’s New Look remained in style…and really, it still hasn’t gone anywhere. The difference is that with this second wave of feminism, women’s clothing styles broadened. As if to reflect the freedoms they were, and are still, fighting for, choosing how to dress, whether it be a mini skirt and peasant top or an aline dress with an apron, became a freedom all in itself.

Today, when the name Christian Dior is heard, we think of couture gowns, sparkly fabrics and soft, sexy perfume ads. We also think about the gorgeous hourglass shape that his original dresses revolutionized. What we don’t think about is the repression that those dresses, as beautiful as they were, represented for the women of the time. In 1947, his debut collection was equated to “the Shot Heard ‘Round the World”, reforming the bore of rationed fashion. Whether the designer intended it to revert society into old ideas or simply meant to bring some sparkle back into a world that had been dulled by war, that “shot” ended up being a spark (albeit one of many) to light the match for a new wave of the fight for women’s rights. Today, we have the privilege of being able to see these gowns and admire their beauty. To learn from the technique and talent behind the designs. As we praise the collection for its famed place in fashion history, may we also learn from and appreciate its place within women’s history as well.

Cheers!

Sources:

Komar, Marlen. “Hidden Histories: When Women Protested Dior's Famous 'New Look'.” It’s Rosy, Https://Www.itsrosy.com.

“The Second Wave of Feminism.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/topic/feminism/The-second-wave-of-feminism.

Taster, Michaella. “How the 1950's Housewife Was Expected to Behave in the 'Good Wives Guide'.” Stay at Home Mum, 4 Feb.

About the Creator

Chelsea Adler

Obsessed with fashion. Obsessed with dark history. Even more obsessed with escapism through a good story whether it's reading or writing one. Spice is a plus. This page is a combination of all of that. Enjoy 🖤

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.