COSTERMONGERS IN VICTORIAN LONDON

Even common thieves preferred to prey on shop owners rather than costers, who were inclined to dispense street justice.

Queen Victoria’s reign was the costermonger’s pinnacle, even though the word had been devised in the early sixteenth century. Costers were far from well-off; there were over thirty thousand of them, quite a big number in London, which was just under two and a half million.

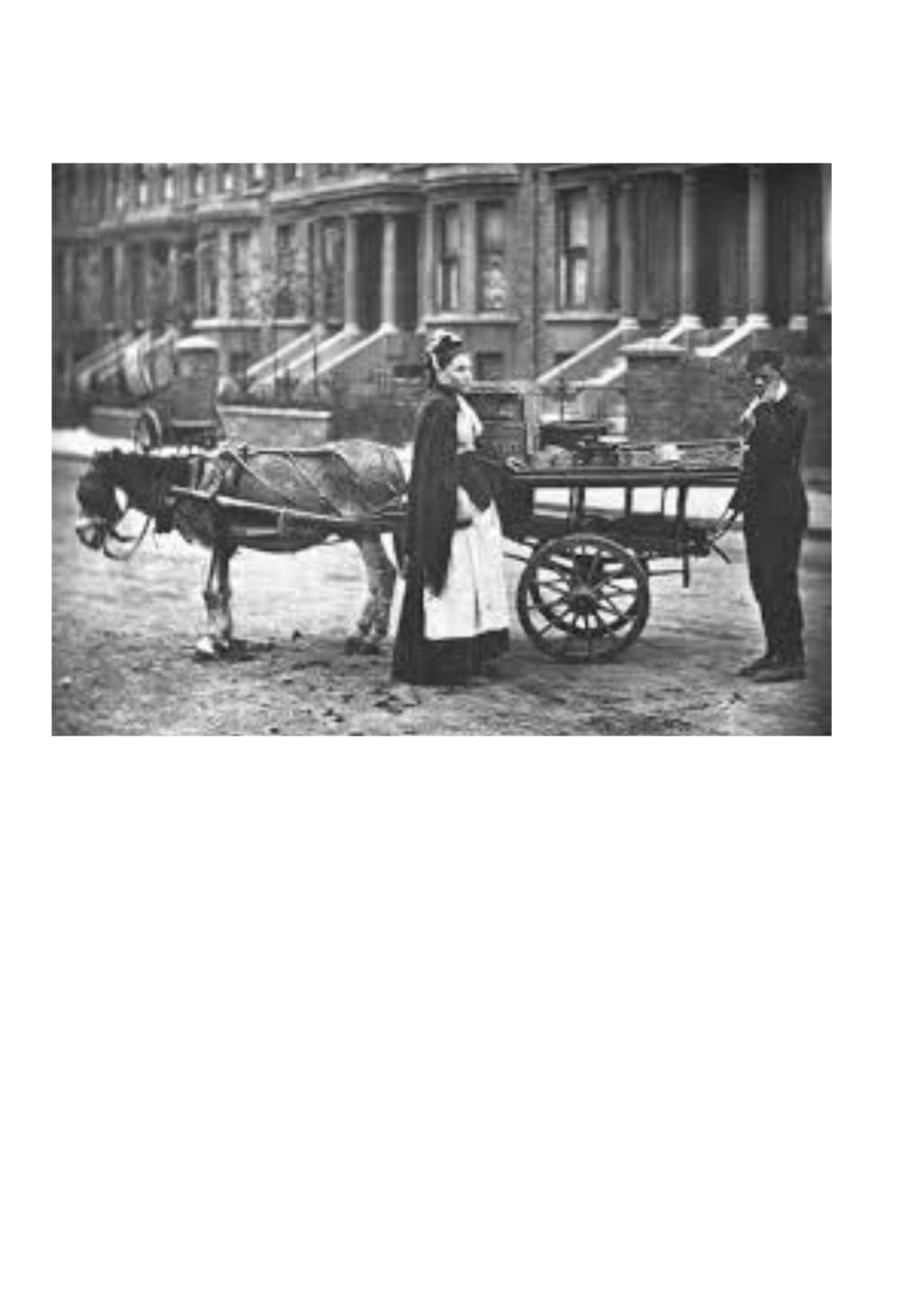

There is no mystery about what costermongers did. It was simple they purchased fruit and vegetables wholesale, then sold them retail. Strictly, they were hawkers, since just a tiny number had fixed stalls. Others shouted out their goods as they strode the streets with barrows and donkey carts. In the 1840s, they accounted for ten per cent of the cheaper produce sold in Covent Garden’s wholesale market. They also accounted for a third of Billingsgate’s fish.

Costermongers’ wages averaged eight shillings per week. Saturday night and Sunday morning were their most profitable days. Men were paid on Saturday evening, while Sunday’s dinner had still to be purchased. Three or four rainy days in a row brought the costers close to starvation. The occupation itself was extremely seasonal, and January was their starvation month.

There were around thirty large street markets in London where costers lived together in courtyards and narrow streets. Home for a family was almost always a single room. Yet, costers resided most of their lives on the streets.

For a lot of costers, gambling was usual. Typically, they betted in the beer shops. They mainly played cards or three up, which was a game played by pitching three coins up in the air. They also boxed for side bets. The fights were very brief since the winner was the first man who drew blood.

In those days marriage was rare in the coster society; around ninety per cent just lived together. Men were free to do what they wanted, but women were expected to be loyal and could be beaten up for even speaking to the wrong man.

The costers had their own dress code. In the 1840s, they sported long waistcoats of corduroy with brass buttons stamped with a fox or stag’s head. Mother of pearl set off the blacker ones. Trousers were of corduroy too, and bell-bottomed. Boots often had motifs of hearts, roses and thistles. Cravats called king’s men were of green silk.

In the 1880s, a man named Henry Croft who had long respected the costers’ way of life and their panache smothered his suit with pearly buttons arranged in geometric decorations. Costermongers soon acknowledged the public loved these sparkling outfits and began wearing more heavily adorned outfits and quickly became known as Pearly Kings and Queens.

The Costers established their own culture and in the costermonger community, you could be nominated as pearly kings and queens. This was to help keep the peace amongst rival costers. However, offences such as theft were unusual among costers, especially in a market where they looked out for each other. Even everyday thieves favoured targetting shop owners rather than costers, who were liable to distribute their own street justice.

Costers also established their own language. In the 1800s, they spoke in slang; in which words are said backwards. They included ecilop for police; yob for a boy; and yennep for penny. Back slang was used as a secret language, which only other costers comprehended.

The costers disbelieved all authority, be it the law or government. They also detested the police and would waylay them when they could, showering them with stones, bricks, and bottles. Double-dealing was widespread. They compressed weights to make them look larger and heavier. Measures were fixed with false bottoms so that a quart measuring pot might hold under a pint.

Over half, the coster people were coster born and bred. Girls could actually start work at six, selling vegetables in the day and peanuts in the taverns at night. Boys of seven or eight joined their fathers, often providing a shrill voice for the street cries, as adults were typically hoarse from shouting their wares. Very few coster children attended school, even to the cheap Ragged Schools of the time. Between two to three thousand costers were thought to be Irish, who were driven out of Ireland by the famine. Thousand were people down on their luck: labourers, servants, greengrocers and assistants. These late-comers fared badly, being middle-aged and inexperienced in all the dodges.

The number of costers declined in the second half of the 20th-century. Most of them taking up pitches in the controlled markets. But still today, locals and tourists continue to flock to London’s markets. Today, there’s an enormous range of markets across London, from farmers’ markets to antique markets.

About the Creator

Paul Asling

I share a special love for London, both new and old. I began writing fiction at 40, with most of my books and stories set in London.

MY WRITING WILL MAKE YOU LAUGH, CRY, AND HAVE YOU GRIPPED THROUGHOUT.

paulaslingauthor.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.