Ancient Roman Navy!

Warfare of Classical Antiquity Republican Fleet Anatomy Roman Navy!

Military mastery of the oceans could be a critical aspect in the success of any land operation, and the Romans were well aware that a formidable naval force could deliver troops and supplies to where they were most needed in the shortest amount of time. Naval boats might also feed besieged ports under enemy attack and, in turn, blockade ports under enemy control. A strong fleet was also required to fight with pirates, who caused havoc on commercial sea-traders and, on occasion, blockaded ports. However, maritime combat had its own set of challenges, with bad weather being the greatest threat to victory, which is why naval battles were primarily restricted to the months of April and November.

Click here to see the full video.

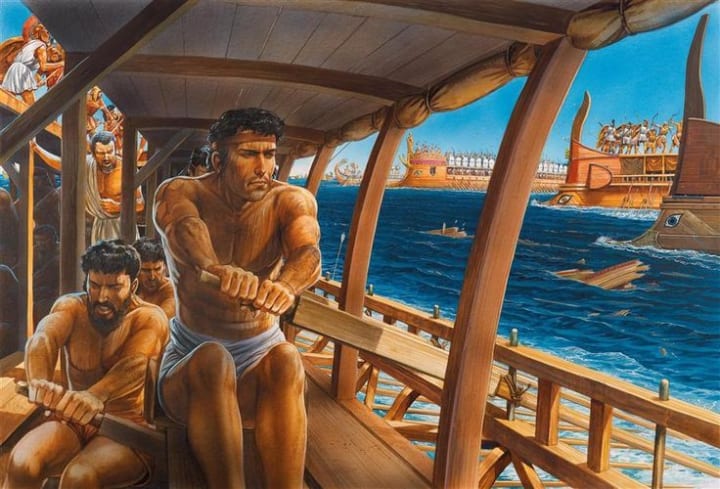

Ancient naval boats were built of wood, were water-proofed with pitch and paint, and were driven by sail and oars. Ships having many layers of rowers, such as the trireme, were maneuverable and quick enough to ram opposing warships. The quinqueremes were the biggest ships, having three banks of rowers, two for each of the upper two oars and one for the lowest oar. Ships might also be outfitted with a corvus platform, which allows marines to readily board opposing vessels (raven). Most battleships were lightweight, cramped, and lacked space for stores or even a big body of men. Trooper carrying boats and supply ships under sail were better suited for such logistical reasons. Other armaments, in addition to the bronze-covered battering ram beneath the waterline on the ship's prow, included artillery ballista, which could be put aboard ships to fire fatal salvos on enemy ground forces from an unexpected and less defended flank, as well as against other vessels. Fireballs (pots of flaming pitch) might also be thrown at the enemy vessel instead of ramming it.

Click here to see the full video.

The emperor nominated a prefect (praefectus) to command fleets, and the role needed someone with exceptional expertise and leadership characteristics to successfully manage a fleet of sometimes ungainly warships. A ship's captain had centurion rank or the title of trierarchs. Fleets were located in fortified ports like Portus Julius in Campania, which had artificial harbours and lagoons linked by tunnels. Crews of Roman military boats may be trained in such ports, but they were more soldiers than sailors because they were expected to serve as light-armed ground troops as needed. Indeed, they are commonly referred to as miles (soldiers) in papers and burial monuments, and they earned the same pay as infantry auxiliary and were subject to Roman military law. Crews were mainly recruited locally and from the poorer classes (the proletarii), but might sometimes include recruits from friendly nations, prisoners of war, and slaves. Training was thus an essential prerequisite to ensure that the collective manpower was deployed most efficiently and that discipline was maintained in the midst of the chaos and horror of combat.

Click here to see the full video.

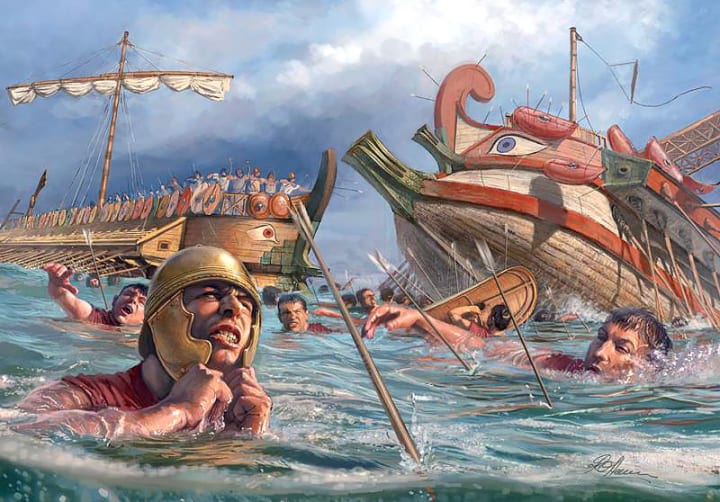

The procedures used by the Romans changed little from those used by the ancient Greeks. Rowers and sail powered vessels to transport soldiers, and in naval fights, the vessels became battering rams with their bronze-wrapped rams. Because sailing maneuverability was restricted in combat, rowers powered the vessels while they were at close quarters with the enemy. Sails and rigging were stowed on shore, saving weight, increasing vessel stability, and freeing up space for marines. The goal was to position the ram such that it might punch a hole in the opposing vessel and then recede, allowing water to enter the wounded ship. Alternatively, a well-aimed swipe might shatter one of the enemy's oar banks, rendering it inoperable. The ideal angle of assault to do this kind of damage was against the enemy's flank or rear. As a result, not only was manoeuvrability under oar required, but so was speed. This is why, over time, vessels piled rowers on top of each other rather than along the ship's length, which would make the ship unseaworthy. Thus, the Greek trireme, with three tiers of rowers, evolved from the bireme, which had two levels, and the trireme finally evolved into the Roman quinquereme.

Click here to see the full video.

Rome had used naval boats since the early Roman Republic in the 4th century BCE, particularly in reaction to the danger of pirates in the Tyrrhenian Sea, but it wasn't until 260 BCE that they created their first large navy in a mere 60 days. In response to Carthage's threat, a fleet of 100 quinqueremes and 20 triremes was built. The designers, in true Roman manner, replicated and improved on a captured Carthaginian quinquereme. The Romans had also recognized their inadequacy in comparison to the vastly more accomplished Carthaginian naval warfare. As a result, they used the corvus. This was an 11-metre-long platform that could be dropped from the ship's bow onto opposing ship decks and secured with a massive metal spike. The Roman warriors (about 120 on each ship) could then board the opposite vessel and quickly dispatch the hostile crew. The Battle of Mylae off the coast of northern Sicily in 260 BCE was the first time the corvi were used effectively. With 130 vessels each, the two fleets were evenly matched, but the Carthaginians did not bother forming battle lines since they did not anticipate the Romans to be any good at naval warfare. The corvus became a devastatingly effective offensive weapon against the disorganized Carthaginians, resulting in a Roman triumph, although an unexpected one. Caius Duilius, the commander and consul, not only had the joy of witnessing his opposite number depart his flagship in a rowing boat, but he was also awarded a military triumph for Rome's first big victory at sea.

Click here to see the full video.

The Battle of Ecnomus, fought in 256 BCE off the southern coast of Sicily, was one of the biggest sea confrontations in ancient history, proving that Mylae had not been a fluke. The Romans, emboldened by their initial victory, had increased their fleet to 330 quinqueremes, with a total of 140,000 troops ready for war. With 350 ships, the Carthaginians set sail, and the two vast fleets met off the coast of Sicily. The Romans organized themselves into four wedge-shaped squadrons. The Carthaginians attempted to draw the front two Roman squadrons away from the back two, catching them in a pincer maneuver. However, whether because to a lack of maneuverability or a failure to communicate objectives, the Carthaginian fleet instead assaulted the Roman rear transport squadron, while the front two Roman squadrons wreaked havoc inside the Carthaginian center. In close-quarters combat, seamanship meant little and the corvi meant everything. Victory was once again Rome's. Carthage lost 100 ships versus the Romans' 24. However, the conflict lingered on as Rome's initial invasion of North Africa proved a costly disaster. In 217 BCE, a major expedition headed by Gnaeus Servilius Rufus freed Italian waterways of Carthaginian pirates, and the Romans finally defeated the Carthaginian navy, primarily because they were able to replace destroyed ships and men faster in what became a war of true attrition. Victories were interspersed with defeats, such as the loss of 280 ships and 100,000 soldiers in a single storm off the coast of Camarina in south-east Sicily in 249 BCE, but Rome finally triumphed. The battle had cost Rome 1,600 ships, but the reward was well worth it: dominance over the Mediterranean. This maritime control proved crucial throughout Rome's Macedonian Wars with Alexander the Great's successor kingdoms. For example, between 198 and 195 BCE, Rome staged successful seaborne attacks against Philip V of Macedon's ally, the Spartan dictator Nabis.

Click here to see the full video.

Piracy became rampant in the first century BCE with the collapse of Rhodes, which had for ages policed the Mediterranean and the Black Sea to defend its profitable trade routes. More than 1,000 pirate ships, frequently organized along military lines with fleets and admirals, were now the bane of maritime commerce. They gained confidence as well, gaining triremes and even assaulting Italy proper, attacking Ostia and interrupting the vital grain supply. In 67 BCE, Rome gathered another fleet, and Pompey the Great was tasked with clearing the seas of the pirate nuisance in three years. Pompey split his army into 13 zones and led a squadron across Sicily, North Africa, Sardinia, and Spain, with 500 ships, 120,000 infantry, and 5,000 cavalry at his disposal. Finally, he sailed towards Cilicia in Asia Minor, where the pirates had their bases and where Pompey had purposefully permitted them to congregate for a last decisive fight. Pompey arranged a pirate surrender with a sweetener of free land for those who surrendered quietly after attacking by sea and land and winning the battle of Coracesium. The final challenge to Rome's total dominance of the Mediterranean was passed.

Click here to see the full video.

The main threat to Rome was now Rome itself, and as a result, civil conflict decimated Italy. The remains of Pompey's fleet constituted the backbone of the Roman navy, which was utilised effectively in the attempts to conquer Britain - the bigger second expedition in 54 BCE comprised a fleet of 800 ships. Following Caesar's death in 44 BCE, the fleet was taken over by Sextus Pompeius Magnus, the son of Pompey. By 38 BCE, Octavian, Caesar's successor, needed to gather another fleet to counter Sextus' threat. Marcus Agrippa was given command of 370 ships, which were sent to assault Sicily and the navy of Sextus. A dearth of well-trained sailors pushed commanders to innovate once more, and Agrippa chose physical force over maneuverability, employing a catapult-propelled grapnel on his warships. This technology enables ships to be winched into close quarters to allow marines to board. The weapon was devastatingly effective at the 600-ship battle of Naulochos (Sicily again) in 36 BCE, when Sextus was defeated.

Click here to see the full video.

One of the most major naval battles in history took place in 31 BCE at Actium on Greece's western coast. Octavian was still fighting for control of the Roman Empire when he met Mark Antony and his ally, the Egyptian queen Cleopatra. Both sides built a fleet and prepared to assault the other. Mark Antony commanded a fleet of 500 warships and 300 merchant ships against Octavian's similar-sized army, albeit Antony's boats were bigger and less maneuverable. Agrippa, who was still in command, began his attack early in the sailing season, catching Antony off guard. The northern outposts of Antony's men were targeted, creating a distraction while Octavian landed his army. Antony, on the other hand, refused to be dragged from his fortified harbour in the Gulf of Ambricia. Agrippa's only choice was to blockade. Perhaps Antony was biding his time until his legions arrived from all over Greece. Octavian, on the other hand, refused to be pulled into a land conflict and hid his fleet behind a protective mole 8 kilometers to the north. As sickness decimated his men and Agrippa's supply lines became more jeopardized, Antony had no choice but to try to break out on September 2nd. Antony could only assemble 230 ships against Agrippa's 400, owing to a defector handing Octavian his plans and other generals switching sides. Agrippa's plan was to keep station at sea while luring Antony away from the coast. However, this would have exposed Antony to Agrippa's warships' better maneuverability, so he sought to hug the coast and prevent encirclement. As the wind picked up about midday, Antony sensed an opportunity to escape since his fleet was sailing while Agrippa's had stowed their sails on shore, which was common procedure in ancient naval warfare. Cleopatra's 60-ship squadron fled the fight as the two fleets collided and clashed. Antony swiftly followed suit, abandoning his flagship in favor of another vessel and leaving his fleet to be smashed by Agrippa and Octavian's combined troops. Soon after, Antony's land army, now without a commander, surrendered to Octavian in exchange for a negotiated peace. The victors' propaganda blamed Cleopatra and Antony's cowardice for the defeat, although the fact that Antony attacked Agrippa under sail implies that, despite being outnumbered, he had meant escape rather than fight from the outset.

Click here to see the full video.

Following the Battle of Actium, the new Roman emperor Octavian, now known as Augustus, built two 50-ship fleets, the classis Ravennatium in Ravenna and the classis Misenatium in Misenum (near Naples), which remained in existence until the 4th century CE. Later fleets were headquartered in Alexandria, Antioch, Rhodes, Sicily, Libya, Pontus, and Britain, as well as one on the Rhine and two on the Danube. These ships enabled Rome to respond rapidly to any military demands around the Roman Empire and equip the army in its numerous wars. In reality, Rome's ships faced no actual maritime rivalry. This is shown by the fact that Rome was involved in just one more big naval fight in the following centuries - in 324 CE between emperor Constantine I and his opponent Licinius - and so, at least in the ancient Mediterranean, the days of large-scale naval battles were finished after Actium.

About the Creator

Father of History

Welcome to Father of History!

Your mind-blowing History channel!

All about History and Mythology in one place.

Our goal is to create educational resources that will make people love history and mythology.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.