Alien Foundlings: The Green Children of Woolpit

Fairies? Extraterrestrials? Flemish?

A curious tale from the 12th century tells of a brother and sister who emerged from the ground in England, speaking a strange language and wearing strange clothes. But most startling of all was their bizarre green skin - an explanation for which has yet to be found.

Were they visitors from another world? Fairies? Were they suffering from some weird disease?

THE STORY

The earliest reports of the Green Children that can be found come from 12th-century historians William of Newburgh (The History of English Affairs) and Ralph of Coggeshall (English Chronicle).

William and Ralph both tell the same general story but differ in some particulars.

One day, the villagers of Woolpit in East Anglia found two confused children, a boy and a girl, who appeared to have emerged from a pit. William claimed that this occurred in the time of King Stephen and the villagers who found them were harvesters in the fields. He also said that the pit they emerged from was one of the "wolf-pits" that gave the village its name. Ralph specified in his account that the children were brother and sister.

They had green skin and spoke an unknown language. William wrote that they were dressed in oddly colored clothing made of a material that the villagers could not identify. Ralph wrote that the children were taken to the home of Sir Richard de Calne, at Wike Hall near Bardwell, six miles away.

Both authors agree that they refused to eat any food for some time. According to Ralph, the girl later explained that they thought the food they were offered was inedible. Then, by chance, they saw some freshly cut bean plants and made it known that they wanted them. They at first attempted to find the beans in the stalks. When they could not find them there, they became upset and wept. A bystander showed them that the beans were in the pods, and the children ate them eagerly.

For several months, they would eat only beans, but eventually began to consume normal food and began to lose their bizarre green coloring. Both authors seem to have assumed that this return to a normal color was the result of their diet. The children also learned to speak English and it was decided that they should be baptized.

According to Ralph of Coggeshall, it was during this period when they would eat nothing but beans that the boy, who had been sickly since their discovery, languished and died. William of Newburgh's account differs in that the boy, who he specified seemed younger than the girl, died shortly after baptism.

Regardless of when the boy passed, they both agreed that the girl flourished and went on to live for many years. However, they both have pretty different accounts of her character and eventual fate.

Ralph wrote that she lived in the service of Richard de Calne, but she "remained very wanton and impudent" (Clark, 2018). William, on the other hand, wrote that she "was not in the least different from the women of our race" (Clark, 2018) and went on to marry a man from Lynn.

Ralph wrote that the girl was often asked about where she came from and that she described it as a place where all the people and all things that existed were dyed with a green color. She said that no sun rose there, but it was always twilight. She claimed that she and the boy found themselves in Woolpit after following their father's cattle into a cavern. Once inside, they heard the sound of bells and, entranced by it, wandered in the cavern for a long time before they found a way out.

When they emerged, they were dazed and stunned by the bright sun and the warmth of the air. They lay at the mouth of the cave for a time before they were frightened by the sound of people approaching. They tried to flee, but could not find the entrance to the cave before they were caught.

William wrote that, once the children could speak English and could be questioned, they claimed to be from "the land of St. Martin, who is regarded with peculiar veneration in the country which gave us birth" (Newburgh, n.d.). When asked where this land was, they replied that they did not know.

In William's account, they heard the sound of bells while tending their father's flocks and were entranced. They then found themselves among the inhabitants of Woolpit in their fields.

When questioned, they claimed that their homeland was Christian and had churches. When asked whether the sun rose in that land, they replied: "The sun does not rise upon our countrymen; our land is little cheered by its beams; we are contented with that twilight, which, amongst you, precedes the sun-rise, or follows the sunset. Moreover, a certain luminous country is seen, not far distant from ours, and divided from it by a very considerable river" (Newburgh, n.d.).

Some modern accounts claim that the girl came to be known as Agnes, though this was not mentioned in either Ralph's or William's accounts. At least one retelling of the story (Johnson, n.d.) claims that the girl went on to marry Richard Barre, the archdeacon of Ely, and that they had at least one child.

A CLOSER LOOK

We should probably take this story with a grain of salt since medieval historians aren't exactly known for their accuracy.

William of Newburgh relied upon earlier sources. He rarely cited those sources and added quite a bit of information to them. He also, as with most of his contemporaries, relied quite heavily on eyewitness accounts, preferring people of "repute" (clergymen, nobles, etc.) with local knowledge. He also gave credence to accounts passed on and vouched for by people that he personally trusted. Ralph of Coggeshall's methodology was much the same.

This is problematic since eyewitness testimony is notoriously unreliable. We now know that someone's memory of an event can be influenced by anxiety/stress, leading questions, or reconstructive memory. (Memories are actually generalizations built around previous experiences, rather than an event recorded like a videotape.)

Modern scholars are unlikely to accept that an event happened based solely on eyewitness accounts. Even if William's sources were as trustworthy as he believed, their testimony might be flawed or inaccurate.

One must also consider that William's account, at least, was written some forty years after the fact. Ralph's account was most likely written around the same time.

Another point to consider: Both accounts say that the children refused to eat until they saw bean plants and demanded them. So clearly they recognized the plants as being foodstuffs. Why, then, if they recognized the plants, did they expect the beans to be found in the stalks instead of the pods?

No account seems to have an explanation for this, or for why the fresh-cut plants were brought in on their stalks. This would not have been common practice.

The beans being consumed in Woolpit during this period would have been faba (or fava) beans - also known as broad beans - since other types were later introductions into the area from the Americas. They are best plucked in their pods while young. Harvesters at the time would have known to pluck the lower pods and leave the plant growing so that they could get a second crop. Similar methods are employed by modern gardeners, the ripening pods being plucked by hand over weeks.

Ralph and William's accounts also do not explain why the children would think that ordinary food, such as bread, would be inedible. It could be that what they were presented with was so different from what they were used to that they simply could not recognize it as food, but this seems unlikely.

Historian John Clark (2018) speculated: "There exist in the everday world of reality many cultural and religious reasons why people abstain from particular types of foodstuffs, or insist that food must be processed or cooked in certain ways . . . Was this the sort of objection the children had to the food they were given?"

Only in William's account is the children's clothing described as being of an unusual color and made of a material they could not recognize. Since he gives no more detail than this and we can not say for certain what color the villagers would have thought of as unusual, or what materials would have been known to them, it is probably pointless to speculate on this detail. We just don't have enough information to draw conclusions.

While both authors seem to have believed that the children's unusual skin color was related to their diet, some theorize that their skin was actually dyed. This theory is based on Ralph's use of the words "tingebatur" and "tingerentur." The Latin verb tingo/tingere means to immerse, color, tinge, or dye, which seems to be its usual connotation in medieval texts.

As Clark (2018) states: "Although the verb did sometimes have a more generalized meaning 'to impart colour to something,' it is tempting to conclude that Ralph, or one of his informants, believed that the children's skin had been dyed or artificially stained green."

Paul Harris, in his theory (more on that later), hypothesized that the children came from a family of Flemish immigrants who perhaps worked in the cloth working industry. He suggests that they either dyed themselves by accident or did it intentionally as an attempt at camouflage to hide from anti-Flemish violence. Either way, this theory doesn't quite hold up.

In the medieval era, while there were natural vegetable sources of green dye (such as

nettles, ferns, foxglove, etc.), they were neither rich enough nor stable enough to see common use in cloth dying. Instead, medieval cloth workers would first dye fabric indigo and then yellow. So, it wasn't likely that there would have been a source of green dye for them to either accidentally or intentionally cover themselves in. If there was such a source, it probably wouldn't have been the type that would have lasted as long as the children's coloring supposedly did.

THE THEORIES

To some, the children's inability to speak a recognizable language and their strange clothing would suggest that the children were simply foreigners.

Woolpit is situated along a route that was used by travelers from two major ports and had a shrine of the Virgin Mary that attracted pilgrims. It was also close to Bury St Edmunds, a town with an annual tradition of international trading fairs that would have attracted foreign merchants. These fairs would have been at their peak during the 12th century.

It is possible that merchants traveling to this fair could have passed through Woolpit or just north of it and somehow lost track of their children.

Paul Harris, in the journal Fortean Studies (1998, 1999), theorized that the children were from a family of Flemish immigrants, possibly weavers or cloth workers, living in England. He posited that their family lived a few miles away from Woolpit in a town called Fornham St. Martin (perhaps the explanation for "St Martin's land"), and had suffered some sort of attack, possibly as a result of Henry II's attempt in 1154 to banish the Flemish from England. The children could have fled their home in the aftermath and found their way to Woolpit.

He points to the Flemish reputation for excellently dyed and woven textiles as explaining the children's strange clothing. However, since the original accounts are so lacking in detail when it comes to their clothing, there is nothing to point out that their clothes were specifically of Flemish making.

While there were Flemish settlers in England around this time, they were mercenary troops that King Henry II had ordered to leave England that were lying low or serving in the private armies of English noblemen. There is no evidence that Flemish cloth workers settled in England and set up shops to compete with English cloth workers. Nor is there any evidence of such in Fornham St. Martin.

It is possible, however, that Flemish merchants were in the area at the time for St. James's Fair at Bury St. Edmunds. So, if the lost foreigner theory is correct, perhaps they were of Flemish origin. It's certainly possible, but there isn't enough evidence to say.

This, of course, doesn't explain their strange coloration, but an explanation for this could possibly be found in some sort of medical condition.

There was a theory, popular in Woolpit at the time, that the children's unusual coloring was due to being poisoned with arsenic by their wicked uncle. It is unclear where this rumor came from.

Arsenic poisoning can lead to hyperpigmentation (darkening of the skin), paleness, cyanosis (blue-tinged skin), or jaundice (yellow-tinged skin). Sking turning green, however, even if only slightly, is not a symptom of arsenic poisoning.

One of the more popular natural explanations for the Green Children is that they were suffering from chlorosis or the "green sickness."

Chlorosis was a historical disease that has also been called the "virgin's disease," as it was thought to predominantly affect young, unmarried women. Early accounts of the "virgin's disease" described a variety of symptoms such as delirium, fever, torpor, numbness, paleness, and suppression of menstruation. They also describe symptoms that could be considered as much psychological as physical, such as depression and wanting to eat strange inedible things, such as dirt or rocks.

Sometimes mentioned is a greenish pallor, although the pallor described does not match the vibrancy of the Green Children. Furthermore, a greenish pallor as a symptom did not seem to be a defining characteristic of the disease, being reported only a few times. It has been put forth by some scholars that the "green" in "green sickness" didn't refer to skin color but to the sufferers themselves - "green" here means "immature" or "inexperienced."

Chlorosis was directly attributed to the patient having no sexual contact and was thought to be a result of a thwarted biological drive to reproduce. It was considered to be a feminine weakness, despite cases of men presenting the same condition. This thinking persisted for an embarrassingly long time, up until the end of the 17th century when it gradually started to be examined a bit more scientifically.

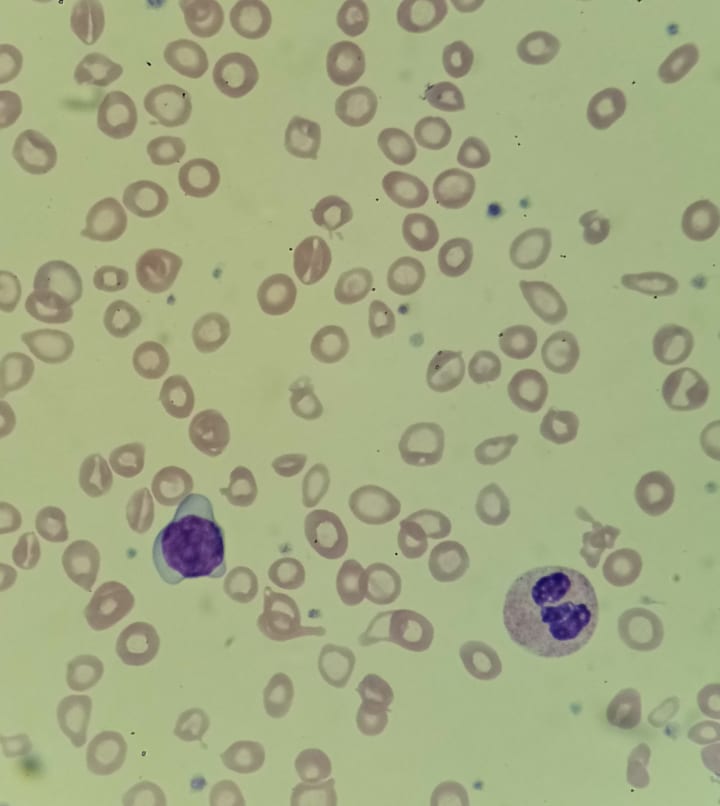

Today, it is generally recognized that the disease formerly referred to as chlorosis is a condition known as iron deficiency anemia, a type of hypochromatic anemia.

Anemia itself is not a disease but a symptom of any number of disorders. It's a condition in which someone lacks healthy red blood cells, which are responsible for carrying oxygen to the body's tissues. Iron deficiency anemia is caused by insufficient stores of iron in the body, either through blood loss, dietary deficiency, or defective absorption. Without sufficient iron, the human body can't produce enough hemoglobin, the stuff in the red blood cells that lets them carry oxygen.

Iron deficiency can be mild, with symptoms so slight they go unnoticed. But as the condition worsens, so do the symptoms, ranging from fatigue and shortness of breath to chest pains and headaches. Another symptom is unusual cravings for non-nutritive substances such as ice, dirt, starch, etc. If left untreated for long enough, iron deficiency anemia can lead to more long-term issues, like heart problems.

But does the green tinge that some patients present in accounts of chlorosis match up with the description of the Green Children?

Well, no. In both older accounts of chlorosis and modern accounts of iron deficiency anemia, skin discoloration has been noted, but references are usually to a pale or yellowish color. Only rarely in older accounts was it described as green, and even then it was nowhere near the vibrancy implied by Ralph and William. It was certainly never described as covering the entirety of the body.

So, while a good guess and a sound attempt at a logical explanation, the symptoms just don't match up.

The children's recognition of and refusal to eat anything other than beans has led some to put forth favism as an explanation for their strange coloring.

Favism (G6PD deficiency) is a hereditary disorder involving an allergic reaction to the fava bean. Those susceptible to it can develop hemolytic anemia by eating the beans or even by exposure to the pollen. Symptoms can include paleness or yellowing of the skin (jaundice). But no green. Once again, the symptoms just don't match up.

One must also consider: Why, if the children had been living on beans for long enough to develop hemolytic anemia, could they not recognize that the edible beans are found in the pods and not the stalk of the plant?

While it's not unlikely that the Children's coloration was caused by some sort of medical condition, it is not immediately clear what sort of condition it was. None of the candidates put forth so far seem to fit.

EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY OF TRAUMATIZED CHILDREN

Something that should be considered while thinking about the story of the Green Children is the account the children themselves gave and just how reliable it could have been.

This is not to say that the children were intentionally lying, but we've already covered just how unreliable memory and eyewitness testimony is. Further, it's not likely that they ended up wandering by themselves, possibly suffering from a sort of sickness, due to a pleasant series of events. These children were likely traumatized in some way.

As unreliable as eyewitness testimony is, eyewitness testimony from children can be even more so. Children imprint memories differently than adults since memories (as stated before) are built around past experiences. They are also more likely to create false memories, as has been seen before - most notably during the "Satanic Panic" of the 1980s.

These instances of false memory usually occur when children are asked leading questions. Leading questions can also cause the child to answer with whatever he or she thinks will most likely please the adult asking. Remember that, in William's account, the girl said that the sun never rose in their homeland after being specifically asked whether the sun rose there. There's a perfect example of a leading question, so we know that they were asked at least one. There were probably more.

It was also said that they were "often asked" about their origins, so it doesn't seem too far-fetched to think that a creative child would start to give out the fantastical details that the persistent adults around them seemed to crave.

SO, WHAT'S THE TRUTH?

Disappointingly, there are no firm conclusions here. The original, maybe-not-so-reliable sources are simply too vague in detail to draw answers from and none of the theories fit well enough to lend any true credence.

The theory that the Green Children were separated from foreign merchants on their way to festival seems logical enough and seems the most likely of current theories, but lacks any real evidence and is impossible to prove.

Given the age of the story and the lack of details, it remains extremely unlikely

that this one will ever be "solved." However, it remains a fascinating story. One that is possibly more folkloric than historical, but going into that is beyond my scope.

Fortunately, it is not beyond the scope of John Clark, Emeritus at the Museum of London, who has written several papers on the Green Children of Woolpit.

For an examination of the children's place in literature, read his "Small Vulnerable ETs: The Green Children of Woolpit." For a truly impressive deep dive into the Green Children, including their folkloric and historical context, read his "The Green Children of Woolpit."

SOURCES

Anemia. (2003). In Miller-Keane Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health. Retrieved from https://medicaldictionary.thefreedictionary.com/hypochromic+anemia

Clark, J. (1999). The green children: A cautionary tale. Fortean Studies 6, pp. 270–7. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/10302407/The_Green_Children_A_cautionary_tale

Clark, J. (2018, Jul. 11). The green children of Woolpit. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/10089626/The_Green_Children_of_Woolpit

Cockayne, E. & E. (n.d.). A short history of Woolpit. Retrieved from http://www.woolpit.org/history/index.html

Davis, C.P. (n.d.). Arsenic poisoning. Retrieved from https://www.medicinenet.com/arsenic_poisoning/article.htm#arsenic_facts

Dr. Chris. (n.d.). Arsenic poisoning symptoms and signs of toxicity, exposure. Retrieved from https://www.healthhype.com/arsenic-poisoning-symptoms-and-signs-of-toxicityexposure.html

Favism. (n.d.). In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/science/favism

Iron deficiency anemia. (2016, Nov. 11). Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/iron-deficiency-anemia/symptomscauses/syc-20355034

Johnson, B. (n.d.). The green children of Woolpit. Retrieved from https://www.historicuk.com/CultureUK/The-Green-Children-of-Woolpit/

Just how reliable is a child eyewitness? (2005, Jul. 21). ABC News. Retrieved from https://abcnews.go.com/Primetime/Health/story?id=965740&page=1

Kahn, A. & R. Nall. (2019). Hemolytic anemia: What is it and how to treat it. Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/health/hemolytic-anemia

McLeod, S. (2018). Eyewitness testimony. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/eyewitness-testimony.html

Newburgh, W. (n.d.). The History of William of Newburgh: Book one. Retrieved from https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/williamofnewburgh-one.asp#27

Ralph of Coggeshall. (n.d.) In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ralph-of-Coggeshall

Smith, D. (2002, Mar. 18). Foundlings wrapped in a green mystery. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2002/03/18/theater/foundlings-wrappedin-a-green-mystery.html

Starobinski, J. (1981). Chlorosis — the ‘green sickness’. Psychological Medicine, 11, p.459–68. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/85221641.pdf

William of Newburgh. (n.d.). In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-of-Newburgh

About the Creator

B. Jessee

Appalachian writer & nerd. Writes about the strangest bits of history and science as well as science news.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments (1)

Fantastic! The green children sounds interesting! Great work!