What they don’t tell you about digital DNA data storage

More needs to be done to ensure accessibility of the emerging technology

A few years back, a TED talk featuring scientist Dina Zielinski caught my attention through a seemingly mundane plastic tube. With a twinkle in her eye, she held it up and proclaimed, “I can fit all movies ever made inside of this tube. If you can’t see it, that’s kind of the point.” What she was referring to wasn’t a magic trick, but a ground-breaking concept: DNA data storage.

Zielinski’s talk continued, focusing on the DNA’s three famous virtues. One is its density (as mentioned earlier). Two, its durability (potentially lasting millions of years without the need for electricity). Third, DNA’s universality as the code of life ensures continued compatibility with future reading and writing technologies. Such positive portrayals of the biomolecule in the context of data storage have been reverberating across press releases and social media posts, painting a utopian vision of its application. DNA-based data storage is emerging as the heralded ‘ultimate solution’ to the challenges stemming from our exponential data generation. It offers infinite storage for indefinite periods.

However, while these prospects of DNA data storage look promising, as with many technological breakthroughs, underneath its promotional veneer might lie an area for scrutiny and critique. I feel that after several years of almost blind promoting of the technology, the public needs to be shown a balanced view rather than an all-out embrace. One area that deserves closer scrutiny is the social and cultural challenges that may arise from archives that are made/encoded with DNA.

DNA-Based Archives

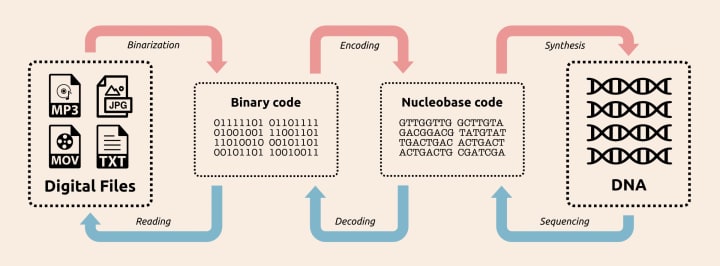

So what kind of data storage would the DNA-based technology allow? The commonly talked about application — at least in the early phase of its rollout — is for archiving. DNA data storage not only consumes high monetary investment, but it also is time-consuming, both to sequence data into DNA and to extract data. For these two reasons, the current recommendation from the experts is to use DNA storage for archival.

But here’s the thing: when it comes to storing data in DNA, there’s a missing piece in the conversation — ensuring these archives stay accessible to everyone, especially for things that are highly valued across societies, such as cultural heritage. It’s not just about preserving information; it’s about creating an environment where everyone can actually access and make sense of this valuable historical data. Accessibility in archives means breaking barriers so diverse users can tap into this wealth of information for research, learning, and preserving our cultural heritage. History has taught us that making archives accessible is crucial, and there are countless examples to prove it, too many to list here.

Accessibility Challenges

The way I see it, there are at least three types of accessibility challenges that DNA data storage faces, which need to be adequately addressed in preparation for the rollout of the technology.

DNA is Physical

First up, is about accessing the very archives themselves. Unlike digital data, DNA archives are physical — inconspicuous and invisible, yes, but still tangible molecules. You can’t just click and access them online. It’s not like cracking open your phone; you either have to physically be there to read it or rely on someone else to do the reading for you, which can then be sent digitally. What’s more, reading and writing require physical machinery to perform them. These archives are often in specific places, which can be a real hassle for researchers or anyone who can’t visit those spots, limiting access big time. Plus, let’s face it, DNA won’t survive a nuclear blast.

The DNA Elites

Next, there’s the intellectual side. Understanding how this DNA archiving works isn’t a walk in the park. There’s a learning curve to grasp the mechanics of it all, especially since it’s a whole new way of doing things. There are concerns about the synthetic DNA, the potential confusion from the public who may conflate them with naturally occurring DNA, and data security risks like hacking or corruption, making it hard for people to trust the tech. Like how some struggle to understand digital archiving methods (e.g., blockchain), this new DNA system might baffle many. Further confusion may also arise from the fact that this synthetic DNA can be inserted into living organisms, such as bacteria and plants, which may draw criticism and concern about the ethics of modifying nature and safety issues around data harbouring organisms to go awry with mutations and escape into the wild.

Then, we’ve got accessibility to the tech itself. Early on, companies and governments might monopolize the technology. This could lead to potential economic and political divides. Gatekeepers with different motives could control metadata or who can access what. High costs might also lock out those keen on archiving but unable to afford it, creating yet another divide, like the digital gap we’ve seen before.

Moving Forward

Before this DNA storage goes mainstream, we have some serious accessibility hurdles to clear. Granted, the technology is still in its infancy. But we should not wait until we have these important conversations. This will give us more time to prepare and expect damaging situations. It might compromise the preservation of cultural heritage.

I recommend cultural heritage organizations and those who want to create and curate archives with DNA to work closely with the gatekeepers of DNA data storage technology.

They will have a say in how the technology is implemented. The DNA Data Storage Alliance (DDSA) fosters collaboration. Founded in 2020 by Illumina, Microsoft, Twist Bioscience, and Western Digital, DDSA’s membership continues to grow. At the time of writing, there were 36 officially approved members in the form of academic institutions, co-operations, and state-sponsored organizations operating in various fields and industries. Some of the members include Seagate, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Cinémathèque Suisse, Quantum, and The Claude Nobs Foundation, to name just a few.

The physical nature of DNA-based archives creates accessibility challenges. People must engage with gatekeepers, such as companies and governments, to ensure that forthcoming legislation or guidelines account for these accessibility concerns. One potential approach could involve a hybrid model. Partly digitize archives as a backup. Then, use DNA-based setups for the remainder. This balance would ease digital sharing and accessibility. Companies must consider and explore this avenue if they haven’t already done so.

To enhance intellectual accessibility, we must improve outreach and educational initiatives. It’s essential to introduce archives to potential users. Also, educate them on effective access and utilization of these valuable resources. This could involve organizing workshops, outreach programs, or creating online tutorials. They would dedicate themselves to navigating archival materials. About this, the DDSA aims, in the short term, to ‘educate the public and raise awareness about this emerging technology of DNA data storage and its immense potential in preserving our digital legacy.’ However, specific details about the proposed activities and the strategies to achieve these objectives are yet to be fully disclosed or published to the best of my knowledge.

Finally, in considering technological accessibility, an ostensibly effortless (albeit perhaps lazy) approach that some might entertain is to simply do nothing and bide our time until the costs and overall accessibility become more inclusive for a broader demographic. However, this passive stance risks being too late if we aim to leave our imprint on cultural heritage — an opportunity too profound to forfeit due to prolonged waiting.

An alternative, more proactive strategy involves advocating for the democratization of technology. This entails initiating efforts to persuade elitist companies and governments to reduce entry barriers and broaden their customer base, thus enhancing accessibility for all. This involves fostering open-source initiatives, enforcing regulations to prevent monopolies, and allocating public funds to support innovative start-ups. Additionally, providing accessible education and training programs, encouraging collaborative partnerships, establishing interoperability standards, and engaging communities in decision-making are crucial steps.

By employing this multifaceted approach, the goal is to promote fairness, encourage innovation, and ensure that technological advancements benefit a wider spectrum of society, democratizing access to technology and diminishing the influence of elitist entities in controlling technological landscapes.

In a Nutshell (or a Test Tube )

The emergence of DNA data storage has brought about vast amounts of enthusiastic portrayal and media’s positive narratives touting the technology as the ultimate solution to manage the overwhelming volume of data humanity generates.

However, this seemingly utopian concept demands scrutiny, especially regarding the accessibility challenges inherent in DNA-based archives. Three distinct types of accessibility challenges loom physical accessibility of the archives themselves, intellectual comprehension of the technology, and accessibility to the technology. Physical access involves the inconvenience of accessing tangible DNA archives, limiting widespread access. Intellectual comprehension hurdles arise due to the complexity of the technology, causing potential confusion and security concerns. Furthermore, monopolization, high costs, and technological barriers pose significant challenges to broad access.

Addressing these challenges necessitates proactive measures. Collaborating with technology gatekeepers, advocating for legislative considerations, and promoting hybrid archiving models integrating digital backups alongside DNA storage can enhance physical access. Improved outreach and educational initiatives are crucial for intellectual accessibility. The DNA Data Storage Alliance (DDSA) exemplifies such collaborative efforts, aiming to educate the public, yet specific strategies remain undisclosed. Encouraging democratization through open-source initiatives, regulatory enforcement, community engagement, and accessible education are vital steps toward broadening accessibility and mitigating the dominance of elitist entities in controlling technological advancements.

Hope you enjoyed the article, for a more critical take on DNA data storage, here is a link to my recent publication titled Navigating Imaginaries of DNA-Based Digital Data Storage.

About the Creator

Raphael Kim

Independent researcher, writer, and educator: On topics around microbes, DNA, and AI. Ph.D in hybrid bio-digital gaming with living microbes

Comments (1)

I was not familiar with this and still not clear but you tickled my curiosity- I saw “Consider this: a single gram of DNA can store hundreds of petabytes of data” this in article after searching. So to be clear - is the DNA here not human DNA but data? Over my head…. Good article!!