The exactitudes of 2015's Ex Machina might have passed from your memory, but the sci-fi film's influence is still felt by many within the industry. Made for a relatively small budget (as science fiction films go) of around $15 million, Alex Garland’s film was a smash hit with both audiences and critics. New Scientist magazine called it “a much needed shot in the arm for smart science fiction.” It was deemed “smart sci-fi” by a host of other reviewers: a benchmark to which later science fiction films should be compared.

As a stream of fictional female artificial intelligences are just around the corner (think Blade Runner 2049, Anon, and Replicas, to name just a few slated for a 2017 release), Garland's film will certainly once more enter the public discourse. But should Ex Machina really be considered a benchmark of quality in science fiction? The film has faced some criticism as to its portrayal of a female artificial intelligence, but it has otherwise unwaveringly been lauded as thought-provoking sci-fi fare.

But I don't think so. Ex Machina not only gets the artificial female wrong; it gets the whole discourse around artificial intelligence wrong.

Here’s the gist of the film, in case it’s been a while. Mad-scientist type Nathan (Oscar Isaac) lives alone in a modernist mansion within a jungle resembling the Lost island. He has recently completed work on the most hyper realistic artificial intelligence being in existence. He invites fledging programmer Caleb (Domnhall Gleeson) to perform a Turing Test on this particular A.I., whom he has named Ava (Alicia Vikander).

Think of Nathan as a sort of Tony Stark character. Both are geniuses in every possible capacity, but they also really like to party. They've got the full package: the sharp wit, the defined abs, and the questionable pruned facial hair. They both work in isolation and produce impossibly complex machines, of which no competent team, even one composed of competent, non-alcoholic individuals, has ever been capable. Indeed, Nathan, boy genius, creator of obvious Google surrogate Blue Book, he whose laboratory walls are coated with a mass of sticky notes, has need of no collaborators.

I'm not versed enough in Iron Man lore to know whether Tony Stark ever built himself a sex robot, but that's really all Nathan's ever thought to build. Ava, Nathan’s sexy A.I., is a reflection of Nathan's human vices. Her molded robot behind, strange functional vagina, and beautiful face are so superfluous to a puritanical conception of A.I., that they, in fact, become the movie's central focus. Sure, the film’s characters take turns congratulating Ava's language abilities and complexity, but Ava couldn't pass a Turing Test for her robot life. In fact, the test was failed the moment Nathan told him, straight up, he'd be taking it.

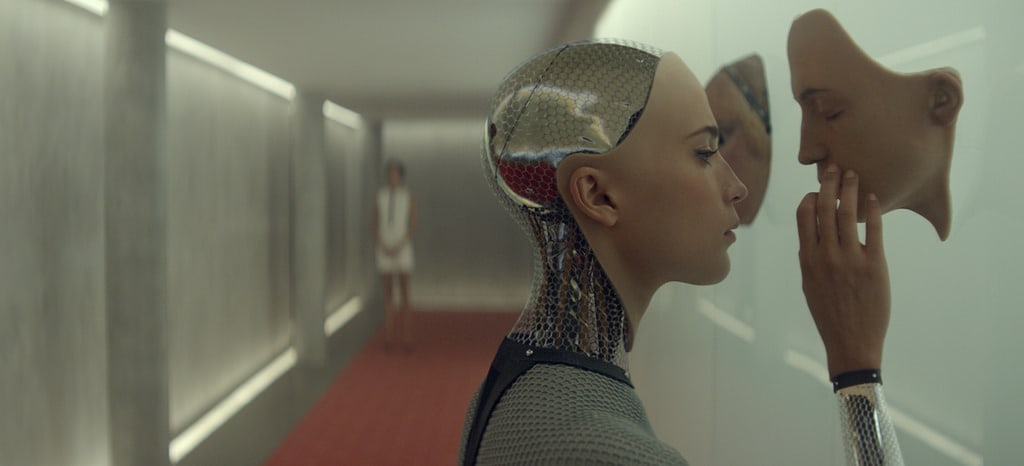

Ava's an impressive piece of machinery primarily because she's got an indistinguishable face from a human. In every other aspect, I wonder whether Nathan’s intention was to sabotage his own test. Ava looks calculatedly robotic. She's a composite creature of mesh, wires, and a see-through head. Certainly, Nathan had the capacity to fix this aspect: he has the spare flesh to put Buffalo Bill off murder. Moreover, Nathan has skinned all previous models as to be indistinguishable from humans. So why, then, does Ava only have skin on her face, feet, and hands?

The short answer is “aesthetics”, but let’s revisit that in a moment.

Caleb does point out that in a "real Turing Test" the A.I. in question should be hidden from the tester. A Turing Test is meant as an ‘imitation game’, to find out whether a robot’s answers to predefined questions might be mistaken for those of a human. It is not meant to align with the Singularity when artificial intelligence reaches our own nebulous measure of human intelligence and then surpasses it. A Turing Test is simply to measure that a machine can simulate humanity, not that it has necessarily become it.

And Ava simulates many aspects of humanity so poorly it astonishes. Why does she — supposedly Nathan’s most advanced creation— make the whizzing of a toy helicopter whenever she turns even slightly on her joints? It serves only to mark Ava further as a piece of machinery. Again, we’re shown Nathan has the capability to produce entirely silent robots: a dead giveaway that the whir was, again, an aesthetic choice made by the filmmakers, rather than by Nathan himself.

Nathan answers Caleb that a test with a hidden Ava would prove too easy. If he were to only hear Ava’s voice, she would obviously “pass for human." Well, not so fast. Ava’s speech pattern is elite but undoubtedly juvenile. She asks Caleb a range of questions; from his “favorite color” to “do you like me?” and “do you want to be my friend?” and “is Caleb your friend?” Ava doesn’t seem capable of simulating maturity: she declares her age to be "one", and provides precise profit numbers for Nathan's Blue Book on cue as well as formal definitions for popular human phrases.

It would have been a great fix to make Ava into a child, but her endowed sexuality is so central that the act of her dressing is a backward burlesque, synced to sensual binaural beats. She is confusedly sexualized and infantilized, which is why Caleb abstains from sexual play with Ava with a level of curious disgust straight from The Graduate. A few interesting questions come out of this: is he concerned with the ethics and whether a sexual relationship with Ava may fit on the spectrum of bestiality? Can he sense the innocence behind that shapely encasing?

And if it is not the Turing Test, what is Ex Machina attempting to answer? At the movie's end, what breakthrough are we meant to believe Ava has achieved?

Nathan, at last, defines Ava as a "rat in a maze", intended only to manipulate her surroundings for the ultimate goal of escape. And if you can believe it, this exact same measure of intelligence popped up into another 2015 sci-fi blockbuster: Jurassic World. "He's intelligent," declares Chris Pratt's character, when the artificially-created dinosaur creates a distraction in order to open the gates to his freedom. The measure of artificial intelligence in Hollywood may apparently be visualized by a rat escaping from a maze.

Science fiction, as a speculative genre, is only valuable when it asks the right questions. Marred by a campy fixation on robot sexuality and an unfortunate ignorance of key A.I. concepts, Ex Machina not only doesn't answer the question advertised, it doesn't seem to understand the question.

And when Ava does escape out into the world of the real, all I can wonder is: does she ever manage to get rid of that whirring?

[To hear more on the depiction of artificial intelligence in Hollywood, check out my podcast episode "Asimov vs. the Robotic Uprising" above. To debate me on Ex Machina, or really any other topic, feel free to email me and we'll get the conversation going!]

About the Creator

Ari Brin

I'm a postgraduate student in Science Fiction at the University of Dundee. I have a passion for futurism and science fiction's rich history. You can check out my podcast, NOVUM, on iTunes, or get in touch with me at [email protected].

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.