The triumph of liberal democracy is no doubt a foregone conclusion. In fact, Fukuyama's ideal polity is the product of great political forces and a particular historical moment. Democracy itself is of course a very old political principle, which seems to be based on the naive idea of rule by the people, or dēmos. The central idea is that individuals should not be seen as powerless individuals under the whip of a tyrant, but should be able to participate in the establishment of governing institutions and rules. To achieve this, they must have the opportunity to participate actively in political life.

Throughout human history, this democratic system has been articulated in many ways and in a range of political institutions. Among these methods is direct de-mocracy, in which all laws are decided by direct popular vote among the members of society, as citizens in ancient Greece did by convening assemblies more than 2,000 years ago. The other is indirect democracy. For example, we elect members of Parliament, who represent the views of the people in their constituencies and participate in making laws on their behalf. But rule by dēmos is not always seen as the best or most successful form of government, either in direct or indirect democracy. In fact, democracy has been criticized by many people at all stages of its history.

The Greek philosopher Plato accused democracy of inspiring mob rule, in which the many impose their will on the few through discrimination and oppression. By the time the Athenians were conquered by the Macedonian king in 400 BC, democracy was an absurd political system that was not universally appreciated. Despite the improvement of political decision-making mechanism case - since the 13th century is the most famous British "parliament" (parliaments), the establishment and expansion of the centuries, political power is concentrated in the hands of the ruler of irresponsible. In Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, when our modern nation-state was just emerging, the most attractive political proposition was not "people power," but absolute authority by guaranteeing that the crown was answerable only to God. In the wake of the Protestant Reformation, it was widely assumed that only absolute sovereignty could prevail over the disorder and violence raging in Europe and ensure the safety of the people. Democracy, by contrast, is widely seen as messy and dangerous. James Madison, the chief architect of the U.S. Constitution, always avoided using the definition of "democracy," instead disparaging it as "controversy and turmoil," "usually short-lived in turmoil."

It took about two centuries for democracy to establish itself as an attractive and viable alternative to political organization. Two moments crucial to the revival of democracy were the American Revolution (1775-1783) and the creation of the new United States of America, and the French Revolution (1789-1799), when revolutionaries not only limited the absolute authority of King Louis XVI, but ended the aristocratic system that had supported the crown. According to the British political theorist John Dunn, it was during the revolution that "democracy" expanded from a noun originally used to describe a governing system to a noun generalizing a class of people (" democrat, "Democrat), an adjective expressing support (" democratic," democratic), And the verb (" democratize ", to democratize) used to describe the shift to a political system of human autonomy.

But the process was not entirely smooth: while the protagonists of the French Revolution agreed on what institutions to destroy, they disagreed on what society to build.

Some of them, inspired by the 19th-century French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, believe that true democracy can only be achieved by rulers who directly implement the will of the people -- broadly defined as the will of the majority -- and that rulers of the same society treat all equally. Here Rousseau uses two notions of democracy -- "unanimity" and "equality" -- to challenge the divine power of Kings to make laws and sovereign authority. On the contrary, only a free, equal and mutually beneficial consensus among the people can form the basis of legitimacy authority in a political community and provide the source of law. Therefore, the legislative power does not belong to the ruler, but belongs to the people. After that, it is also known as popular sovereignty. More importantly, the state is no longer seen as part of the natural or divine order, but as a human creation to advance the collective interests of its citizens.

When Maximilien Robespierre became the leader of the French Revolution, the potential dangers of this model were made abundantly clear in a bloody way. In what became known as the age of terror, he held fake show trials and sentenced thousands of citizens to death. In the aftermath of the French Revolution, proponents of democracy grappled with two main questions: First, who should determine the will of the people? Second, what if the will of the majority is morally unacceptable acts such as slavery and mass murder?

A second group of revolutionaries, inspired by the founding fathers of the United States of America, believed that the will of the majority did not always ensure good government. There are two other categories of factors that must be considered. First, drawing on the ideas of the British philosopher John Locke, the father of modern liberalism, they argued that popular sovereignty must be perfected by a set of fundamental rights that would protect the minority from the tyranny of the majority. Second, they believed that the three branches of government -- legislative, executive, and judicial -- should have checks and balances to prevent any one branch from abusing its power. In this system of checks and balances, an independent judiciary is seen as a vital part of the structure of government that can be used to prevent the tyranny of the majority. Respect for the individual, regarded as a fundamental civil and political right, and respect for the rule of law have become important cornerstones of liberal democracy. It is for this reason that most of the world's liberal democracies today have constitutions, which serve as the basis for the conduct of the state, and which clearly distinguish between the various branches of government and arrange for the fundamental rights of every citizen.

The corollary of fundamental rights is to claim that they are universal -- that they belong to all human beings. Another consequence of this is that the revolution of the late 18th century, to a large extent, also started the historical process of defining and focusing on "human nature". This turning point in the extension of conscience and concern began in the 1780s and ended in 1807 when the British Parliament passed a bill formally declaring the abolition of the slave trade movement into practice. The movement to abolish the slave trade was the origin of modern humanitarian action -- not just an act of charity within a nation, but also an act of relief for suffering people living far away. Underpinning this is our universal humanity. The introduction of ideas of liberty and equality in the late 18th century was described by the British historian Jonathan Israel as a "revolution of thought" : it led to a radical change in the way people viewed and thought about social organization, moving from a bureaucratic model to a more egalitarian and inclusive paradigm.

In any case, the democracy that emerged during this period was extraordinary -- representative rather than direct. The definition of "democracy" does not necessarily mean, in its literal sense, the formation of a government governed directly by the people -- as in ancient Greece through assemblies of citizens and show trials -- but by political representatives elected by the people and entrusted to them the power to govern. James Madison noted that this political class would "refine and expand the public's view," discarding the prejudices of ordinary people and refining through their wisdom and experience the broader public good. Moreover, it took a century and a half for the "revolution of ideas" to translate into the visible expression of equality, especially in politics. The first form of democracy, the Athenian city-state, was highly hierarchical: about 30, 000 adult males (about 10% of the population) had political rights, while slaves, foreigners and women had no vote. The earliest liberal democracies also excluded most people from political participation.

While the ideal political vision is one of rule by the people, subject to checks and balances, it is "the people", in a narrow sense, that continues to dominate politics. Three other groups are excluded from democracy. The first is the proletariat. Rich Democrats, a small but politically powerful minority, fear enfranchisement of the poor majority, whose demands are quite different from those of the rich. In Britain, for example, the right to vote was not extended to the majority of the British population until the early 20th century. The second reason why political power is strictly limited is gender. Although suffragists had been politically active since the mid-19th century, it was not until 1918, near the end of the First World War, that women were granted the right to vote in Britain and Canada. In the United States, some states acted alone to give women the right to vote, but it was not until 1920 that this gender-based regulation was lifted. The United States adopted the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. In other Western countries, women did not get the right to vote until the end of World War II.

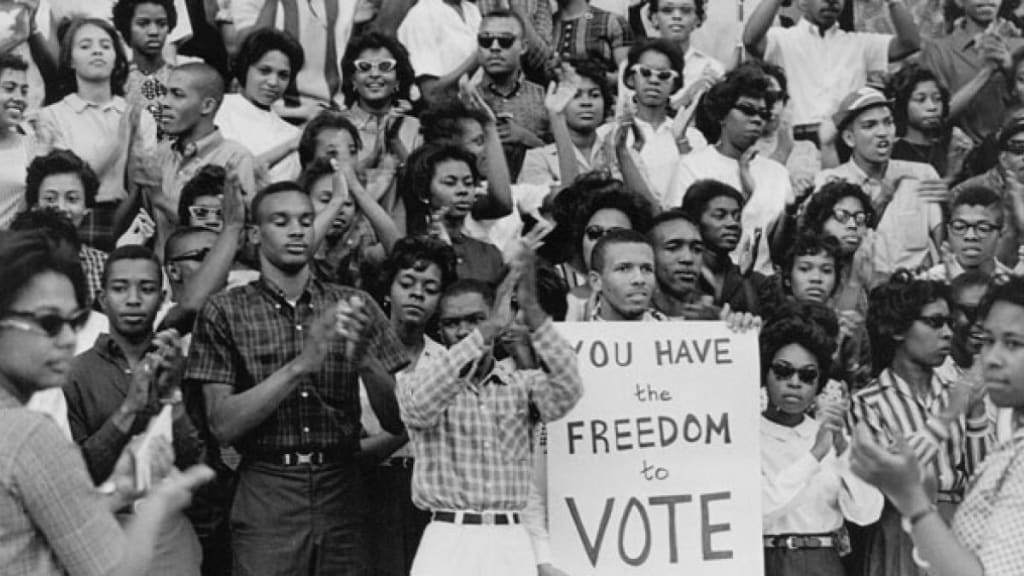

The third and final limiting factor is race. Although early humanitarians, such as the anti-slave trade movement, were largely based on the ideal of common human dignity, in fact they promoted compassion for the "other" rather than genuine equality. The slaves of the abolitionist movement in the 18th century were still far from being "human beings" with civil and political rights. According to the American literary historian Lynn Festa, they have no real rights, "only the right to be exploited." The disenfranchisement of minority political participation continued for more than a century, and became the focus of the postwar civil rights movement in the United States. Although a constitutional amendment gave AfricAn-Americans the theoretical right to participate in American politics, the bureaucratic barriers remained so high that only a small percentage of blacks actually voted. It wasn't until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that AfricAn-Americans became fully "citizens."

The consolidation of democracy, then, requires not just one revolution of thought, but many. The global spread of democracy has been erratic and has had many setbacks. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were only about 10 democracies in the world (by definition 1 at the time). After the first World war, that number doubled, prompting US President Woodrow Wilson's famous observation that "the war has made the world safer for democracies". Within a few years, however, the situation was reversed by economic crisis (plus the Great Depression) and political turmoil. The new Baltic democracies and Poland were dismantled, and the nascent democracies suffered major setbacks in the heart of Europe -- in Spain, Italy, and Germany -- as fascist governments promised their people better order and more prosperity. Meanwhile, in Latin America, military coups overthrew democratic governments in Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina.

In the 1930s, political systems opposed to democracy, such as Mussolini's Italy, Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Soviet Union, all looked more vibrant and successful than the shaky democracies of the isolationist United States, France and Britain.

"People tend to follow winners," Kagan notes. "In the interwar period democratic capitalism looked weak and on the defensive. As a result, by 1941 there were only nine democracies in the world, and Winston Churchill was tempted to lament the "new dark ages" that would come once Britain was conquered by Nazi Germany.

It was the decisive military victory over fascism and the occupation of countries such as Japan, the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and Germany that allowed democracy to usher in a second wave of development after 1945. Potential alternatives to democracy have been eclipsed -- especially when compared with the rapid economic growth, expanding middle classes and strengthening state welfare systems in many Western societies. In fact, the rise of the market economy directly consolidated democratic institutions. This phenomenon also contributes to economic development -- such as high levels of education, smooth population mobility, the rule of law and easy access to information, which also underpins broad and equal political participation.

In addition, by the 1960s, the process of decolonization was advancing, new nation-states were emerging in the developing world, and a number of new democratic regimes had emerged, increasing the number of democratic countries in the world by four times.

It was not until the 1980s, however, that democracy could claim to meet human needs better than its competitors. In retrospect, the third wave of democracy began with the democratization of autocratic regimes in southern European countries (Greece, Spain and Portugal) and in some Latin American countries.

The west also faces the curse of "stagflation" -- high unemployment, high inflation and low economic growth. At this stage, alternatives to democracy seem alive and well, and many theorists are beginning to ask warily whether democracy has reached its limits.

In another 10 years, more than half of the world's population lived under democratic systems, and the number of democratic countries exceeded 100. Liberal democracy -- combined with the rule of the people, the protection of human rights, the rule of law and free markets -- is a worthy winner in the competition for global political and economic dominance. This victory also led many Western political classes to try to spread liberal democratic political and economic models around the world, in order to accelerate the formation of what Fukuyama described as a "universal homogeneous state."

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.