The Donor

A man has to make sacrifices. That's how it's always been.

My hand shakes signing the agreement, and my signature looks so bad I ask the nurse if I should do it over. She smiles and says it’s fine, then escorts me through the lobby, where nervous folks sit under the high glass ceiling waiting for their consultations. I had mine a month ago.

The monitor on the wall starts up the Xeromere ad again, which plays every ten minutes. I’d been seeing it for a year on my phone. That slender, put-together lady who looks about sixty-five, walking towards you in front of a meadowy background. “Hi, I’d like to talk to you about Xeromere,” she says, brushing back her silver hair. “Telomere Transfusion Therapy, or TTT, is on the cutting edge of science, technology, and medicine.”

The nurse opens the door for me, into the transfusion room. It’s narrow like a hallway and dimly-lit. I can still hear the ad lady through the door.

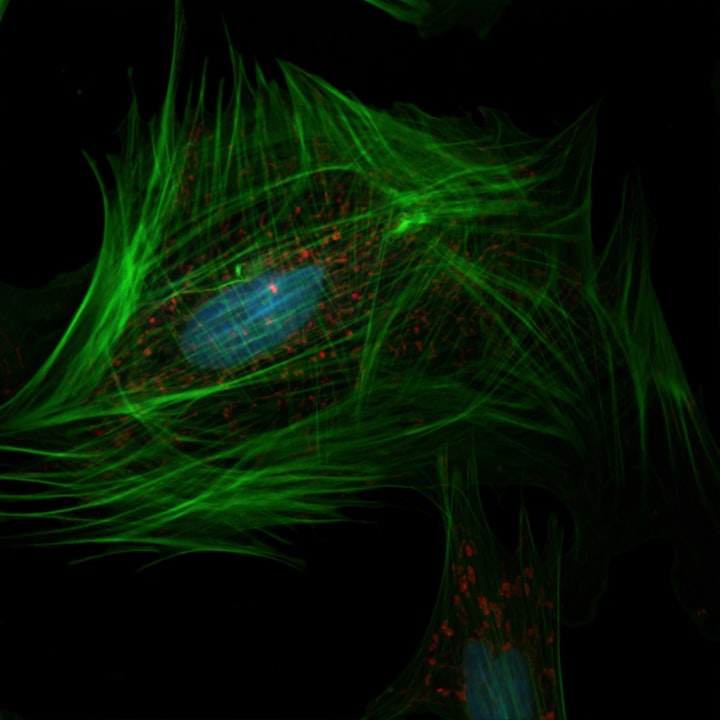

“Telomeres are strands of DNA that sheath the ends of chromosomes and play a key role in immune function and aging. Think of them as shoes on the feet of your chromosomes, protecting them and helping them do their jobs.”

The nurse points me to one of those chairs like they got at the dentist. I see the transfusion machine to my left, big as a two-door fridge, with a metal brace sticking out of its middle like an open mouth.

“Telomeres help our cells replicate so that our bodies can stay healthy and strong. However, each time a cell replicates, the telomeres inside shorten. Eventually, they get too short to do their jobs, like when the soles of your shoes get too worn.”

The nurse pulls a curtain that cuts the room in half, leaving me in the chair next to the machine. There’s a blank monitor on the wall at my feet.

“For all of history, the result was always the same – cells died, and the body aged. However, that no longer has to be the case.” The ad lady’s voice bubbles with optimism. “In 2091, after decades of testing on thousands of people, including myself, Xeromere’s patented TTT process was cleared for public use."

A little air filter behind me turns on with a hum. There’s a twitch in my eye so I squeeze it shut.

“First, Xeromere’s own innovative synthetic enzyme causes excess telomeres to leave the cells of donors. Next, those telomeres are extracted from the donor’s system. Finally, another enzymatic step causes them to find a home in the cells of recipients.”

I didn’t pay much attention to the ad at first. It didn’t sound like anything I could afford. But then I heard you could get paid for donating. Paid a lot. And if my daughter Sela was gonna have a decent chance to do something in this life, I needed a helluva lot. More than I was ever gonna earn working, anyway. So I sent in a skin sample, just to see, and as it turned out, I got perfect telomeres – how you like that?

“By replacing worn telomeres with fresh ones through Xeromere’s unique TTT process, cellular life, and human life, can be extended, giving patients like me more years to spend with the ones who matter most.” Cue folks dressed in white walking into view, a handful at a time, each group younger than the last, and she says, “Like my kids, my grandkids, my great grandkids, and my great-great grandkids.” A final pretty smile at you, and she finishes, “The process continues to improve thanks to the donations of people like you.”

She says that last bit with such warmth I feel a swell of pride. I suppose I should be proud. Sela will get to have a modern education, make something of herself, be a part of things. A man has to make sacrifices. That’s how it’s always been.

I hear the robotic disclaimer voice that talks while the ad lady and her four generations walk offscreen. “Donors acknowledge and accept that transfusion carries with it imminent risk of noncommunicable disease. Donors knowingly and willfully accept all terms of the transfusion contract, including nondisclosure and non-disparagement, and forfeit any right to additional compensation for sustaining any of the harms described therein.” We discussed all that at the consultation. They showed me the statistics, the confidence intervals. I’m thirty now, but chances are I won’t be seeing fifty. I’d probably be a walking tumor by then. But my girl will have opportunity she never would’ve otherwise. And hey, 8% chance I see sixty. That ain’t nothing.

The nurse comes back in. She turns on the monitor, pre-set with a video playlist I’d picked, and tells me to feel free to use my phone, but to remember I’d agreed not to record anything and doing so could void payment. I set my jaw and try to focus on the videos. I can’t seem to distract myself, though.

I stare at the brace on the transfusion machine. It’s got three tubes running from it to the top part of the machine, a poised needle at the end of each tube. The nurse numbs down my left arm with sterile-smelling stuff then clamps the brace over my arm. Don’t they got machines to do this? I suppose they want to be comforting, the human touch before the needles. That must be why the little air filter is wafting the scent of pine and lavender into this dim little room. They know I come from West Virginia, between the forests and the fields, yes sir. My great-great granddaddy mined in the tunnels. My great granddaddy mined when they just cut open a whole mountainside. My regular granddaddy came of age when there weren’t no mountains left, but he made a farmer out of himself. He grew lavender in the sunken hills, in the potash of ten million felled trees. One day he took me out there and said, “Andy, don’t ever forget what ugliness this growed from. Don’t ever forget that this is a land o’ opportunity.”

The first needle comes down, guided by some digital eye, a barely-feelable prick. Clear liquid meanders down the tube into my veins. First would be the enzymes, they told me, that make your extra telomeres fall off.

The monitor seems far away and I can’t get enough air in me. Keep calm, Andy. You’re doing right by your girl.

My right hand goes down into my jeans pocket to feel the locket Grammy gave me before she died. It belonged to her granddaddy, my great-great. A little golden heart with a slender chain and a tiny photo inside. He used to take it down into the mines with him, a photo of his wife and children, to remind him why he was sacrificing, why he was breathing in that black dust, a billion tons of mountain creaking overhead. That photo’s still in there, but now it’s underneath one of Sela. We took it on her third birthday, over the fairy-shaped cake Ma made her.

The other two needles come down, a tube attached to each. My blood goes up one into the machine. A few minutes later, blood comes back through the other tube, telomeres scrubbed out. I shudder.

It’s been so hard for so long. Ma and Daddy were teachers until they were replaced by computer lessons. Daddy said it was nothing new. I was a farmer for a while, like Pap, but then the company that owned the farm didn’t need anyone working it. Then a line cook, but they got a machine and didn’t need me there either. I tried moving to the city, but the rent was so damn high that nothing could be saved. So I went back home, back to my sweetheart, Melinda. We had to scratch and claw just to keep our one-room place, like most everyone else in town, but we were alright. We had our phones, had internet, didn’t need much. Then I got Mel pregnant. It’s all well and good being broke when you’re twenty-five and single, but raising a child? Not these days, buddy.

My jaw hurts. I realize I’d been clenching it and let my mouth gape open.

Someone across the curtain’s getting laid down, clamped in. Must be the recipient, the one buying my telomeres. Paying me more money than I’d’ve made my whole life. Amazing things they’re doing with this stuff. The lady in the ads is over a hundred. I’ve heard they think they’ll have people seeing two, three-hundred even, with multiple transfusions.

I hear a gasp, then panting. It’s my own. Oh God, oh God, I’m going to die. I’m going to die so soon. I’m barely grown. There’s sweat beading on my nose, sudden tears swelling hot in my eyes. I’ve just tried not to think about it but I can’t, I can’t.

No, I’ve got to remember why I’m here. I take the locket out. Open it up and see my girl. Coal-dark hair messy over her green eyes, a baby-tooth smile. Such a beautiful kid. So smart, too, learning to read bit by bit. She deserves better than to be stuck scramblin’ in the boonies because she was unfortunate enough to be born to me. I’m not allowing bad luck to make her life a worthless one.

I hold her little face in front of me and breathe, breathe. I’m doing her right, giving her and Mel a good life. And we’ll have some time, all three of us. 67% likelihood I make it to forty.

I still remember getting the estimate from Xeromere, after I sent in my skin sample. My eyes about bugged out of my head. Sela had a future, all of a sudden. The Xeromere guy told me all the risks at the consultation. He said transfusion’s taking off, and it’s a seller’s market now – few more years and maybe I’d only get half.

We had a tough talk, Melinda and me. It was getting harder every year. There wasn’t much work for a dummy like me. I didn’t want to watch Sela grow up a victim of my failure. I’ll die knowing her and her mother will have prosperity. I hope she’ll understand. You ain’t entitled to a damn thing in this world, but with sacrifice, your children might have it good. I blink my eyes dry.

It’s ironic, I guess, that my great-great granddaddy died of cancer because of his job, and I’m gonna die of it because I couldn’t seem to keep one.

Well, regardless, I’m lucky. You got nothing if you don’t have something that somebody is willing and able to pay for, and most people don’t have diddly. I got my perfect telomeres, going up the tube. That whir, turning my DNA into cash. It’ll be dropped into my account as soon as the needles detach. I’ll walk out that door a rich man past all the other folks praying they get results as good as mine.

We’ll buy a place. No more renting for us. And Sela’ll be anything she wants, an engineer or a businessperson or who knows what. I’ll be forty-eight when she’s graduating college. 39% chance I make it that long.

The ad starts up again in the lobby. “Hi, I’d like to talk to you about Xeromere...”

The recipient says something to the nurse. She comes back, starts turning down the volume on my monitor. “Sorry, you mind if we turn it down a bit?” she asks. Not at all. I get it – he’ll probably be a repeat customer.

I ain’t no genius and I wasn’t born with a silver spoon up my butt, but I’m gonna give my girl opportunity. I hear the machine on the other side of the curtain starting up, mixing his blood with the loose telomeres from mine. Someday it’ll Sela be on that side, getting new life. She’ll get more from it than I’m giving up. She will. She will.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.